Andrew Wade

Andrew Wade

Senior reporter

Going by the government’s attitude towards broadband, you could be forgiven for thinking we were trapped in 2006 rather than 2016, when Facebook was but a twinkle in Mark Zuckerberg’s eye, and Netflix was gearing up to deliver its one billionth DVD.

Today, Broadband Delivery UK (BDUK) - part of the Department for Culture, Media and Sport – classes broadband speeds over 24Mbps as ‘superfast’. Now, while 24Mbps is by no means a shoddy internet speed – and would certainly have been something to shout about 10 years ago – claiming this as ‘superfast’ in 2016 is verging on the embarrassing.

Yesterday’s decision by Ofcom to leave Openreach under the control of BT is unlikely to help the situation. Openreach, established in 2006, has a monopoly over the infrastructure and cables that make up the ‘last mile’ of the UK’s broadband network – the part that runs from cabinet exchanges in the street to homes and businesses. It does this on behalf of the hundreds of communication providers (CPs) around the country that sell services directly to end customers, including BT itself. Unfortunately, underinvestment in the underlying infrastructure has led to record numbers of complaints, and fears that the UK is falling behind when it comes to broadband speeds and coverage.

On the surface, the current state of affairs doesn’t seem terrible. According to 2015 rankings from US company Akamai, average connection speeds here are 13Mbps. This puts the UK ahead of countries such as the US and Germany, but behind nations such as Romania and the Czech Republic. Sweden is the highest ranked European country with 17.4Mbps, while South Korea tops the list overall with 20.5Mbps.

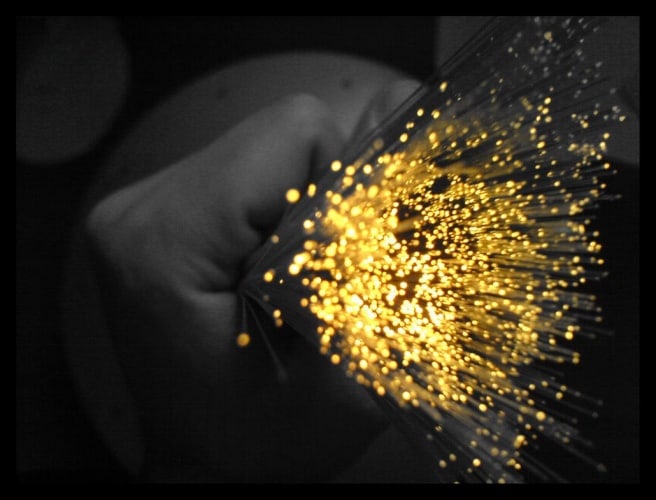

Dig a little deeper, however, and the underlying problems become more apparent. The vast majority of the fibre broadband offered by the UK’s main service providers is Fibre to the Cabinet (FTTC). Fibre optic cables rather than copper wiring transfer massive quantities of data at the speed of light, dramatically improving broadband speeds. But with this fibre only running as far as the exchange cabinets in the street, customers and businesses have to rely on old copper wiring for that ‘last mile’, which dramatically reduces speed.

What the UK needs, and what Openreach has been dragging its feet on, is Fibre to the Home (FTTH). As the name suggests, this bypasses the copper problem, with fibre going direct to the premises and providing speeds as fast as 1Gbps. In fairness to Openreach, delivering FTTH across the UK would be hugely expensive. But it’s an expense that needs to be met if the UK is to remain internationally competitive, and the sooner it happens the better.

Some companies such as Hyperoptic are offering FTTH, but only where it makes economic sense, such as in apartment blocks or business parks where they know there will be substantial take-up. I happen to live in one such block, and Hyperoptic have been making noise about going live in the building for an eternity. The fibre has apparently been laid, but residents have been in limbo for months waiting to hear back from the company as to the current status. With no other access to fibre, Hyperoptic knows it has us over a barrel and is very much moving at its own pace.

These are, I freely admit, first world problems. Having said that, the UK is a first world country, and internet infrastructure is about as important a first world problem as you will come across. Broadband connectivity has become almost as vital as the water and electricity utilities that we depend on for our existence. Granted, you won’t die of thirst or hypothermia if your router goes down, but you will find your channels of communication with the world severely limited, and you will almost certainly find it extremely difficult to do business.

As for Industry 4.0, you can forget all about that for the time being. Currently just 2.6 per cent of premises in the UK have access to FTTH. In Sweden, this number is 56.2 per cent, and in Spain it’s 62.6 per cent. South Korea and Japan have penetration approaching 100 per cent. The fact that BT/Openreach is currently squeezing the maximum out of its weary copper network is helping to paper over the cracks in the system, but if British industry and business is to flourish in the coming years, the fibre infrastructure needs to be upgraded as soon as possible. Ofcom’s decision won’t help that happen.

Red Bull makes hydrogen fuel cell play with AVL

Surely EVs are the best solution for motor sports and for weight / performance dispense with the battery altogether by introducing paired conductors...