The London 2012 Olympic Games showed off British engineering at its best, from the sweeping designs of the Olympic venues to the rising importance of sports technology in training. But engineering was also vital in bringing to life an opening ceremony that blew away the nation’s cynicism and set the mood for what some international commentators around the world have called ‘the best Olympics ever’.

The Olympics were a chance for a prominent British team of experts who have worked on opening ceremonies across the globe, from Athens in 2004 to last year’s Pan-Arab Games in Doha, to make a triumphant homecoming. ‘The UK is the home of large event production, particularly for ceremonies,’ said the ceremony’s technical director Piers Shepperd. ‘To do it in London in front of a home audience was obviously really good. There was a massive trepidation after Beijing, which was obviously a spectacular and huge ceremony, and we were very keen to try and do something different.’

Working on a home Olympics also enabled an unprecedented level of co-ordination between the ceremony’s technical team and the Games organisers from the very start. Shepperd was brought on board back in 2006 — several years before the stadium was even designed — to advise on what was needed to make the ceremony a success. He then worked closely with the engineers at Sir Robert McAlpine and Buro Happold to ensure that the stadium would be ready for whatever demands the artistic team came up with. In particular, this led to a roof design that could support a huge cable-net system (see box), which allowed the ceremony team to fly in scenery, lighting and performers with ease and saw the introduction of panels of light-emitting diodes (LEDs) behind each seat in the stadium, which turned the audience into a giant display screen with greater resolution than ever seen before.

‘They knew the importance of ceremonies right from day one,’ said Shepperd. ‘We didn’t have to argue about the importance of putting in a big cable net; they were prepared to work with us. In total, I think we installed about 600 tonnes of equipment into the stadium roof, which is exceptional for ceremonies.’

It was this ethos of extensive planning and collaboration that was carried through to the task of realising the creative team’s sometimes outlandish vision. ‘I suspect most things that they originally intended we have delivered in some way,’ said Shepperd. ‘Some things that you imagine in your head will be really effective but may not work in reality. And we have issues such as gravity, budget and time, all of which affects what we can do. But for the most part, it’s about finding and understanding what it is they want to do, offering it if we can and, if not, offering an alternative that is spectacular.’

When the first details of the opening ceremony were revealed — including the 40 sheep, 10 chickens and three sheepdogs that were to appear — it sounded as if landscape architecture and husbandry would play more of a role than engineering. But the introductory sequence of a ‘green and pleasant land’ — a romanticised scene of pastoral British life — created a unique challenge for the technical team: the rapid removal of 7,346m² of real turf. Not only did they need to find a surface that would be safe for people to dance across when it had previously been covered in potentially rain-sodden soil, but they also had to co-ordinate more than 2,000 cast members in the ripping up of the grass to reveal a stage set for the coming of the Industrial Revolution. This was just one example of why 8,000 radios were needed, so the stage manager could constantly distribute instructions to make sure everyone was in exactly the right place at the right time.

With the grass removed, the stadium was transformed into a representation of industrial Britain led by Victorian engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel (played by Kenneth Branagh), complete with beam engines, textile looms and seven chimneys reaching up to 30m in height that appeared to rise from underneath the stadium. Although the chimneys were very solid in appearance and each weighed more than one tonne, they were, in fact, inflatable and were filled by fans beneath the stage. Each chimney was rolled via tracks onto a lift in the stage floor and then hooked onto the cable-net system above the stadium. ‘As they’re inflated they’re actually pulled up by the aerial system at the same time as the lift is co-ordinated, so when the chimneys are fully elevated the lift is flat with the finished floor level of the stage construction,’ explained flying technical manager James Lee. A winch with a slip clutch attached to the top of the chimneys and pneumatic dampeners at their bases kept them taught, ensuring they inflated from the top and securing the illusion that they were solid structures rising from the floor.

Next came the ‘forging’ of the giant Olympic rings, which were filled with LEDs to make them glow like molten steel. As one rose from the centre of the stadium, another four flew in from platforms on the roof, positioned precisely to overlap to form an Olympic emblem in the sky. This required some careful programming to compensate for up to 3.5m of deflection in the aerial cables due to the changing loads on the system, which was also controlling the chimneys. ‘You had to make sure you had included all the loads at a particular time on the system, because if one load wasn’t there it would give it a different result so the rings would hit each other,’ said Lee. The process then had to be repeated in reverse to clear the stage while the audience were busy watching ‘the Queen’ and James Bond prepare to parachute into the stadium.

In the next sequence, 32 Mary Poppins characters descended from the sky to do battle with giant puppet versions of villains from children’s literature, while hundreds of NHS nurses danced with 350 beds that lit up with battery-powered LED quilts. Here the cable-net system came into play again, said Lee. ‘The 32 of them were actually loaded from the roof on platforms on four different lines, eight per line.’ At the same time, five ‘dementors’ from Harry Potter took off from the floor travelling at 3m/sec, carefully controlled so as not to collide with anything. And more aerial lines were used to control an 18m-high Lord Voldemort puppet that fired pyrotechnics from its wand.

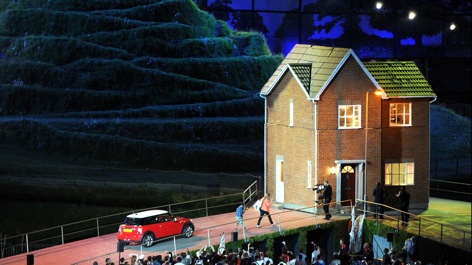

Following a comic interlude from Rowan Atkinson performing Chariots of Fire, the show moved onto a scene focused around a life-size house celebrating British family life and popular culture. The challenge, said Shepperd, was in building something so big so quickly, and once again he turned to an inflatable solution. ‘All of these objects are okay if you’ve got two or three days to install them, but our time target to actually get the house inflated was eight minutes from when it first appeared on the stage.’

As with the chimneys, an under-stage lift and fan were used to inflate the 2m-diameter air beams that made up the house’s skeleton structure. This was covered with lycra to provide a surface onto which 22 projectors positioned around the stadium displayed famous images from British film and TV. At the end of the scene, a smaller house built from foam over a lightweight steel structure was erected. It was so large it had to enter the stadium in two pieces, the top half being lowered via the cable system onto the bottom half that was rolled in, before the whole thing was lifted again to reveal the British inventor of the World Wide Web, Sir Tim Berners Lee.

After a tribute to the victims of the 7/7 London bombing, the athletes’ parade and the official opening of the Games, it was time to light the unique Olympic cauldron, designed by Thomas Heatherwick. It consisted of 204 metal ‘petals’ representing each of the competing nations and each holding a gas-powered flame. These sat on stalks that initially stuck out horizontally but gradually rose as the petals ignited one by one, eventually combining to form a cauldron carrying a huge ball of fire.

‘It was a beautiful object and brought together a number of different technologies,’ said Shepperd. ‘There was the automation in terms of the motors making it move, obviously a very complicated ignition system and then an awful lot of finishing on it. Thomas was very keen right from the early stages, that the mechanics of the machine should be exposed and not covered up.’ The other challenge for the technical team was storing the 23-tonne cauldron under the stage, ready for it to rise up for the lighting ceremony. This meant building the spines to rotate as well as rise so it could be collapsed to the smallest possible size, before being positioned on a 18m-diameter lift ready to appear.

With all this clever engineering, the technical team is understandably proud of their contribution to an event that did an awful lot to raise the country’s spirits and perhaps will influence how the UK is viewed abroad. Soon the eyes of the world will be back on Britain once more for the Paralympics, opening next week. The Engineer was keen to know what that event’s opening ceremony would look like but Shepperd refused to give anything away. ‘You’ll have to wait and see but I’m sure it will be spectacular,’ he said.

Flying tonight

The aerial cable-net system played a major part in enabling the technical team to realise the creative ideas of the opening ceremony. It consisted of 14 radial cables attached to the stadium roof and meeting at a central hub, each carrying two trolleys that could run independently to move scenery and performers around and lower them onto the stage.

Underneath was a another pair of cables running the length of the stadium, each carrying two further winches that allowed the team to position other objects such as a raincloud at the start of the ceremony, a sun during the 7/7 bombing tribute and a flying bicycle fashioned to look like a dove just before the cauldron was lit.

The complexity of the cables created a challenge for the operators. ‘It wasn’t just a case of being able to pull them away and send them back to where they came from,’ said flying technical manager James Lee. ‘We also then had to make sure that, as we plotted cues, we put delays on certain elements so they moved out in a certain time. We decided to use remote winches, which were programmed using a wireless system. Then we used a different triggering system to run a number of cues because the wireless RF [radio-frequency] spectrum was overloaded for the whole ceremony because of the amount of other security and broadcast systems.’

Project to investigate hybrid approach to titanium manufacturing

What is this a hybrid of? Superplastic forming tends to be performed slowly as otherwise the behaviour is the hot creep that typifies hot...