When talking about the strengths of UK industry in the current global economy, it’s often said that we need to concentrate on the sectors where low-wage countries can’t compete. Leave the bulk production to them, and focus on the areas where we can add value. Precision engineering is often singled out here, with the assumption that engineers in developing countries can’t possibly match the expertise or finesse that higher-paid westerners can achieve. The story of Titan Precision Engineering might serve to point out the flaws in that thinking.

Titan is the watchmaking business of India’s giant Tata conglomerate. One of the more recent additions to its mammoth portfolio, it was founded in 1984 as a joint venture between Tata and the Tamil Nadu Industrial Development Corporation, one of the arms of the Tamil Nadu state government. The first company in India to introduce quartz technology, it has since diversified into businesses such as jewellery (where it is part of an effort to improve conditions for jewellery workers, a historically exploited group in India) and both prescription and leisure eye wear. Operating from factories in Tamil Nadu and Goa, it produces watches for a variety of market niches, from simple children’s products to prestige models in precious metals. It has also acquired a Swiss company to allow it to compete at the top of the market.

”Their view before was that India was just elephants and snake charmers

Ravi Kant, Titan board member

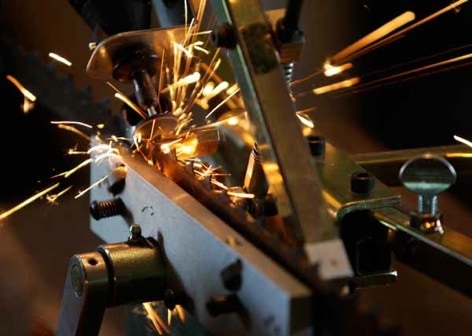

Titan builds watches from scratch, producing every component within its factories and making around 16,000 watches per day in more than 400 different designs. Cases and bracelet links are machined from solid chunks of metal; flat components such as gears are stamped from ribbons of beryllium copper, and cylindrical parts are made on lathes which produce features too small for the unaided eye to see on machines whose tiny, precise movements are obscured by the lubricating oil that bathes all the parts. The Goa operation produces the electronic component for the quartz movement.

It was these machines that were the key to the formation of Titan’s precision engineering operation. In 2006, a re-organisation of the manufacturing operation left the company with some machinery that was no longer being used for watchmaking, as well as the experienced engineers from the maintenance team who were trained to program and operate them. The team had recently built a production line for Seiko, which was setting up manufacturing in India, on a contract basis; so rather than sell the machines and lose the expertise of the engineers, the board decided to investigate what other tasks these assets might be turned to, and decided to set up a machine-building and automation business within Titan, serving its own needs and also offering a service to clients in the wider Tata group and beyond — for example, 80 per cent of Tata cars have at least one subsystem assembled by the automation team.

The precision engineering business now employs 600 people and has an annual turnover of around $40m (£24m), with 25–30 per cent growth year-on-year. ‘The ambition is to go global: we have a target of 80 per cent of income from exports,’ said board member Ravi Kant.

Another example of this machine-building expertise can be seen in the bustling surroundings of Titan’s jewellery business, Tanishq. Next to a room where deft-fingered workers embed diamonds and other gemstones into wax models of rings, pendants and other jewels, a quieter room holds a glass box housing conveyor belts that glitter with cut gems of all sizes. This device uses both machine vision and loadcells to select the groups of stones for individual pieces of jewellery, which are then bagged up and passed out to the setters’ tables in the adjacent room. A bag of stones, a chart, a magnifying glass and a comparison scale are all the jewellers need to set each stone in the right position in the soft wax models, which are then sent off to be cast in 24- and 22-carat gold using the centuries-old lost-wax casting technique; the gems are left held in the gold in the same way as they would be using traditional setting techniques, but considerably faster.

This gem-sorting machine is unique to Tanishq, and represents a considerable saving of both time and manpower. Sorting gemstones by hand is exacting work — each one often measures only fractions of millimetres across and the sizes vary minutely from stone to stone — and carrying it out has contributed to damaging the eyesight of generations of jewellery workers. Other jewellery making businesses worldwide have expressed an interest in similar machines.

The expertise has also attracted attention from some of the stalwarts of the engineering sector, including names that many might be surprised to find source precision components from India. ‘We have produced components for the aerospace, defence and oil and gas sectors. The key is that we produce components to similar tolerances to those needed for watches — and for the machine tools we need to make watches, which have to be even more precise, of course,’ said NP Sridhar, who heads the aerospace business of Titan Precision Engineering. Among the business’s precision engineering clients are Pratt & Whitney and Rolls-Royce, for which it makes turbofan engine peripheral components such as valve parts; Parker Hannifin, which is a customer for automation solutions; heat exchanger maker HS Martson, which is using Titan’s expertise in machining hard metals that can tolerate temperatures up to 900°C (their stability is used to keep watches accurate); and US aero-engine specialist UTC Aerospace Systems, a customer for aluminium and steel actuator manifolds, pistons, sleeves and spools. ‘We were the earliest part of Tata into the aerospace sector and helped the rest of the group develop the skills and disciplines needed in the sector; UTAS was particularly helpful in teaching us to develop the ‘aerospace mindset’ of complying with all the regulations the sector requires,’ Sridhar said.

The customers have undergone a huge change of attitude about the expertise of Indian engineers, said Ravi Kant. ‘Their view before was that India was just elephants and snake charmers,’ he added. Competitors would do well to update their view as well.

Red Bull makes hydrogen fuel cell play with AVL

Formula 1 is an anachronistic anomaly where its only cutting edge is in engine development. The rules prohibit any real innovation and there would be...