Paris. 1940. And with German forces advancing on the French capital, an advanced new aircraft is smuggled quietly out of the city before it can fall into enemy hands.

A vivid shade of blue and startlingly futuristic, the aircraft in question was the Bugatti 100P, the only plane built by legendary car manufacturer Ettore Bugatti.

Boasting a highly streamlined forward-swept wing design and using two cleverly placed engines to drive contra-rotating propellers, the 100P featured a host of innovations that made it one of the most technologically advanced aircraft of its time.

War broke out before the plane could be flown, but Bugatti’s chief engineer on the project, Louis De Monge, projected a top speed of 500mph.

Had the Germans got hold of it — and there’s anecdotal evidence that Albert Speer, Hitler’s minister for production, was aware of the plane — it could have wiped out the aerial advantage of the spitfire and had a profound influence on the outcome of the war.

Fortunately this never happened. The aircraft remained hidden and what remains of the original resides at the AirVenture museum in Oskosh, Wisconsin. It’s too fragile and missing too many components to fly.

But over the years the plane has continued to exert a spell over engineers, who, beguiled by its Art Deco beauty and the mystery of its untested prowess, have long wondered how it would have performed.

Later this summer, a team led by retired US fighter pilot Scotty Wilson hopes to find the answer to this question when its reproduction version of Bugatti’s landmark plane takes to the sky for the first time.

This aeroplane was designed by a guy with a slide rule and pencil in 1937 and some of the stuff he did in that day was absolutely revolutionary.

John Lawson

The project has generated plenty of excitement, not least among the enthusiasts who’ve contributed $65,000 of funding via the Kickstarter crowd-funding site. Some of the more prominent supporters include McLaren design chief Frank Stephenson and US chat show host Jay Leno, who is rumoured to be interested in buying the finished aircraft. But perhaps its biggest champions are the engineers behind the project: a team drawn together by a shared fascination with the aircraft and a deep respect for De Monge.

‘This aeroplane was designed by a guy with a slide rule and pencil in 1937,’ said John Lawson, the project’s engineering director, ‘and some of the stuff he did in that day was absolutely revolutionary.’

Detailing some of the innovations made by De Monge, Lawson — who is the MD of UK firm Lawson Modelmakers — explained that one of the keys to the aircraft’s projected performance was a novel cooling system based on observations made by English engineer Frederick Meredith.

‘Meredith discovered that if you pull cooling air in through a high-pressure area on the aircraft and duct it through the radiator, if the channelling is the right size as it exits the radiator it expands and you get negative drag — and at certain speeds you get positive thrust,’ he explained.

It’s long been thought the P51 Mustang was the first aircraft to make use of the “Meredith effect” and the discovery that De Monge was a few years ahead of US engineers has, said Lawson, prompted a rewriting of the aviation history books. ‘We had a long argument with the P51 Mustang society, he said. ‘They were adamant that this had been created for the Mustang until we showed them the patents from 1937.’

It had poplar on the inside, hardwood on the outside and balsa in the middle. That made it very light and very strong.

John Lawson

Another innovation that was ahead of its time was De Monge’s use of simple analogue sensors to detect the aircraft’s flight phase and automatically adjust the flap and undercarriage system. ‘It knew from what these sensors were telling it what phase of flight it was in,’ said Lawson. ‘For instance, if you were sat on the ground with no airspeed and you opened up the throttle it knew you were trying to take off so would automatically set the flaps in the take-off position. Likewise when you come in to land and start to throttle back and slow down it realised you wanted to land so it would put the flaps and the wheels down.’

Lawson added that the aircraft’s balsa sandwich construction made it one of the first composite planes. ‘It had poplar on the inside, hardwood on the outside and balsa in the middle. That made it very light and very strong.’

But with many of the original blueprints destroyed as the Germans advanced on Paris, recreating the aircraft has been an exercise in engineering detective work and the team has relied on a handful of remaining drawings and careful measurements of the surviving plane in order to determine exactly how de Monge and his team designed and built the original.

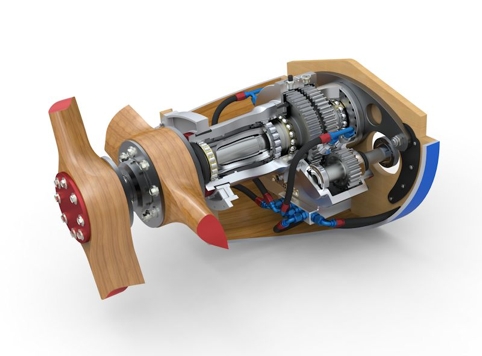

The gearbox, Lawson’s biggest contribution to the project, is a case in point. ‘So little information exists on this,’ he said. ‘There are no drawings apart from an installation drawing, which basically gives you a side profile.’

‘We started by reverse engineering the original box from the photos we had. Luckily someone had taken a load of photographs of one of the spares and he’d put a rule into the picture.’

The team frequently had to improvise however. ‘On the original gearbox the last set of bearings are on the nose of the gearbox itself so the forward propshaft comes out through the rear propshaft unsupported,’ he said.‘That’s fine if you’re going straight and level, but the minute you start pulling any g that little thin propshaft is just going to just bend. So I put a pair of ceramic bearings right up in the nose of the rear propshaft.’

Lawson is keen not to take all the credit for the finished gearbox — which is now being installed in the plane along with the engines, drive lines and flight-control systems — and pointed to valuable help from Vocis, the UK transmission specialist behind the gearbox for the McLaren MP412C and the Lamborghini Aventador.

The team faced a similar challenge when designing the wings and travelled to Oskosh to digitally measure the wing on the surviving aircraft. Models based on these measurements have since been run through a simulator in order to determine how the plane will fly, a luxury that wouldn’t have been available to De Monge. ‘The initial indications we’re getting out are that it will fly very well: it’s got a pretty neutral centre of gravity…because the rear engine can move backwards and forwards we can put the centre of gravity wherever we want.’

With a limited amount of original design detail to go on, the new aircraft does differ from the original in a number of areas. For instance, it uses Suzuki motorcycle engines rather then Bugatti engines, the oil-cooler duct is in a different position and the contra-rotating propellers were designed from scratch by UK firm Hercules. ‘No one can ever build a replica because not enough information on the original exists,’ said Lawson. ‘What we’re building is a reproduction that is accurate in all the key areas and only changes where we’ve had no choice but to change it.’

The group is gearing up to fly the aircraft for the first time later this summer in the US and a European tour will hopefully follow. ‘We want to bring it to Europe. We want to fly in Europe,’ said Lawson. ‘We want to let people in Europe see it — we want to inspire engineers.’

After that, it’s likely that the aircraft will be sold. Although if it flies well, Lawson doesn’t rule out the possibility of making another aircraft. ‘We would consider making another one,’ he said, ‘but we’d probably make it entirely in modern materials so that we could make it quickly.’

Project to investigate hybrid approach to titanium manufacturing

What is this a hybrid of? Superplastic forming tends to be performed slowly as otherwise the behaviour is the hot creep that typifies hot...