Jayne Bryant

Engineering and technology director for Defence Information Solutions and Services (DISS), BAE Systems

With responsibility for around 600 engineers spread across 10 different sites, Jayne Bryant is BAE Systems’ most senior female engineer. And during a fascinating career with BAE (and its former companies) that stretches back 35 years, she has witnessed first-hand great social and technological change.

In my early career it was dreadful. There were a lot of people in the business who thought a woman shouldn’t work

While at school, Bryant thought her aptitude with numbers might lead her to be an accountant or maths teacher, but instead she was drawn to industry. At the age of 17 (knowing next to nothing about the computer technology that was just beginning to make its mark) she joined GEC Marconi as a trainee software engineer.

She came into an industry that was rife with sexism. ‘In my early career it was dreadful,’ she says. ‘There were a lot of people in the business who thought a woman shouldn’t work, if you walked through the main factory you used to get wolf whistled at, and there were pictures of naked women all over the offices.’ It must have been an intimidating environment for a young woman at the start of her career, but Bryant either ignored the idiotic jibes, or fought them with humour. Her response to the calendar incident, for instance, was to put up a calendar with naked men on it.

And despite the difficulties, she thinks that, far from holding her back, being a woman in a male-dominated environment has largely been helpful. ‘I never felt it was a disadvantage, it was almost an advantage because it helped me get noticed a bit more. This only works if you’re good,’ she stresses, ‘and the converse of that is that nobody forgets if you make a mistake.’

Industry has, she adds, moved on dramatically since those early days. Today, though still heavily in the minority, there are noticeably more women engineers and sexist behaviour has, she says, been ‘eradicated out of the business’ by strongly policed diversity regulations and systems such as an ‘ethics helpline’, that employees can use to report unacceptable behaviour.

But although there are more women engineers coming through, Bryant said it’s still noticeable how few make it to senior level, and believes womens’ careers can sometimes lose momentum when they leave to have children; something she experienced first-hand when she had to juggle her career with the demands of triplets in the late 1990s.

Katy Lin

Project engineer in engine and vehicle technology, Shell

When Katy Lin told her teachers and parents that she wanted to become an engineer, their reaction was one of shock. They’d assumed that she would stick to her original plan of becoming a doctor or lawyer.

But her choice to go with her instincts was, she tells The Engineer, the best decision she’s ever made.

Lin — who graduated from Durham in 2011 with a masters in mechanical engineering — is now one of a team of Shell engineers helping to develop and test the automotive fuels of tomorrow, both in the laboratory and on the test track. And she takes great satisfaction from seeing products that she’s helped develop find their way onto the forecourt.

Her decision to pursue a career in engineering was, she says, prompted by a post-GCSE careers aptitude test. Despite receiving little encouragement from her teachers she was convinced that this represented the best way to put her love of maths and physics to practical and rewarding use.

Being able to identify the female leaders and picking them out as mentors to early starters is very important

‘It took a lot of willpower to pursue that goal,’ she says. ‘It’s not something the teachers are familiar with, they’re used to the pure subjects.’

She’s not the first person — and certainly won’t be the last — to suggest that this is something that needs addressing.

Despite being the only female on her team, Lin’s experiences at Shell have been positive. Indeed, far from holding her back, she feels that her gender has been an asset. ‘When you accomplish something as the only woman on the team you get quite a lot of exposure and that can lead onto more opportunities — that’s been great.’

Nevertheless, joining a large male-dominated sector can be daunting and Lin believes that in order to help women enjoy the same opportunities as men, firms should work on developing more targeted mentoring schemes. ‘Being able to identify the female leaders and picking them out as mentors to early starters is very important,’ she says.

Lorraine Blackwell

Composites design engineer, Bloodhound SSC

It’s probably fair to say that Lorraine Blackwell had a lucky escape.

While at school she briefly considered a career in accountancy, but several years later she’s helping to design and build the world’s first 1000mph car: Bloodhound SSC.

An expert in composite materials, which are fundamental to Bloodhound’s design. Blackwell honed her expertise in the aerospace industry during stints at BAE Systems, where she trained as an apprentice; and Airbus, where she recently worked on the new A350 XWB.

Blackwell says she’s always been a very practical person, but although she enjoyed science and maths at school, was given little encouragement by her teachers to pursue an engineering career. ‘If you weren’t really interested in the first place it didn’t really show up, especially for girls,’ she says.

‘I thought I wanted to be a chartered accountant but when I went to try it out for work experience I found myself sitting in an office and thought this isn’t for me. I then did another work-experience placement at BAE and found it so much more exciting.’

There should be more exposure to practical applications of engineering, helping young people better understand how they can tailor their education towards an engineering career

Nevertheless, her career experience as a woman in a male-dominated environment has been mixed.

While enthusiastic about the friendly atmosphere on the Bloodhound team, earlier in her career, when she was a lone female in a team of 500 shopfloor workers, things were less enjoyable. ‘There were always general comments such as “shouldn’t you be in the kitchen?” and all that kind of stuff. I just gritted my teeth and shrugged it off. I didn’t dwell on it too much because I didn’t see the point, seeing a negative attitude towards me made me even more determined to succeed. It takes a certain type of character to survive. You have to take a lot of stuff with a pinch of salt and you have to be able to give as good as you get.’

Although Blackwell believes such attitudes aren’t likely to die out any time soon, she does think it’s getting easier for women and that diversity policies are, at the very least, making people more wary of their behaviour. In the longer term she says industry must do more to engage with schoolchildren. ‘There should be more exposure to practical applications of engineering, helping young people better understand how they can tailor their education towards an engineering career.’

Hannah Stanbury

Apprentice weapons fitter, Defence Munitions Gosport, MOD

When Hannah Stanbury’s grandad spotted a leaflet advertising apprenticeships with his old employer — the MOD’s Gosport munitions depot — he thought it might appeal to his friend’s grandsons. He certainly hadn’t counted on it being intercepted by his own granddaughter.

But more than three years later, Stanbury, who has been shortlisted for this year’s WISE (Women In Science and Engineering) apprentice award, regards her decision to stop studying for A-levels and join the “real world” as one of the best she has made. ‘All of my friends are at uni getting into debt and there’s me learning loads of new skills and getting paid for it as well,’ she tells The Engineer.

Stanbury is now in the third year of an advanced apprenticeship in mechanical engineering, where she’s working on a host of sophisticated weapons systems and missiles.

I don’t think girls are encouraged in the same way; it’s expected that they wouldn’t want to do it.

It’s an environment that she’s clearly cut out for. But despite showing an affinity for engineering while at school, Stanbury had never really considered a career in the profession until she spotted that ad. ‘I wasn’t really the kind of “girly girl” that wanted to go into hairdressing or something like that,’ she says, ‘but I wasn’t necessarily pushed towards engineering either, it just came up and I thought “I’ll give it a go”.’

Despite being the only female apprentice in her year group and one of the only women in the depot, Stanbury’s experience is largely positive, and although she sometimes feels she’s viewed as a bit of a ‘curiosity’, she says she generally feels comfortable and happy at work. ‘When I go into a section they probably are watching to see how I react to things, but I don’t think I’ve ever not got on with someone, or that anyone’s been “offish” with me because I’m a girl.’

Stanbury believes that in order to attract more women, industry needs to offer more encouragement to girls, something she is already helping out with by visiting local schools and talking to pupils about her experiences. ‘It needs to start with schools,’ she says. ‘I don’t think girls are encouraged in the same way; it’s expected that they wouldn’t want to do it.’

Nisrine Chartouny

Project manager for Farringdon Crossrail Station, Bechtel

There are few engineering initiatives in the world more impressive than Crossrail: Europe’s biggest infrastructure project. The construction of the new 21km-long rail line — which will link commuter areas in Essex and Berkshire to the nation’s capital — has presented some enormous challenges, not least the construction of nine new London stations.

Arguably the most complicated of these is Farringdon, which, as well as having to contend with complex geological conditions, is the only station on the route that will which link up with tube and Thameslink services.

In charge of delivering this is 33-year-old Nisrine Chartouny, a Lebanese-born civil engineer who works for Crossrail contractor Bechtel.

Chartouny has watched the station take shape since the initial demolition works began around three-and-a-half years ago. ‘We’re going through a very exciting phase right now because the first of the TBMs [tunnel-boring machines], ‘Phyllis’ finished her 6.5 journey on 7 October: all the hard

work and efforts are reaping the fruit now.’

The biggest influence on her choice of career was, she says, her family. ‘I don’t think I ever thought of doing anything else. My dad is a mechanical engineer and my mum is a civil engineer. We grew up with it. My dad’s a contractor in Lebanon and at weekends on the way to Sunday lunch we would drop in on one of the sites to check progress.’

Often, the main challenge comes from women themselves, especially people who have families and feel guilty, and so give up on opportunities

Her route in the UK sector was circuitous. Educated in Lebanon, she studied civil and environmental engineering in Beirut before heading to the US to complete a masters in construction management. Hired from Lebanon by Bechtel, she has worked on projects all over the world and believes the UK is a good place to be female engineer, particularly when compared to the Lebanese construction sites where she began her career. Now, despite being in a minority, Chartouny says she’s rarely conscious of the gender gap and feels that she is judged by her skills not her gender. ‘I don’t really think abut it that much. I don’t think about the fact that I’m a woman and I’m surrounded by men.’

She claims that the biggest obstacle to women succeeding isn’t a lack of opportunity, but a fear that a successful career isn’t compatible with a family life. ‘Often, the main challenge comes from women themselves, especially people who have families and feel guilty, and so give up on opportunities. You must believe in yourself and go for it. If you’re having to juggle your personal life with your work, others have done it before you and they will support you when you’re doing it.’

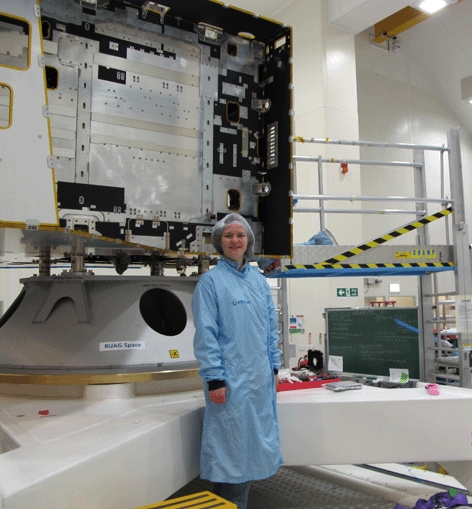

Jessica Marshall

Spacecraft and satellite systems engineer, BepiColombo Mission, Astrium

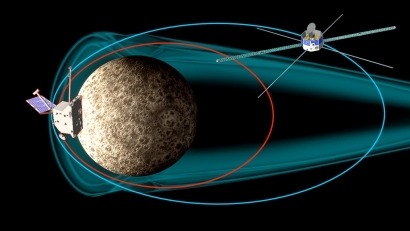

BepiColombo — a joint mission between the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) — is expected to provide scientists with the most detailed understanding yet of our solar system’s smallest planet.

Scheduled for launch in 2016, the mission will see two orbital probes delivered to mercury aboard a third propulsion module: one will examine the planet’s surface and the other its mysterious magnetic field.

During their mission they will encounter some of the most extreme conditions imaginable and much of the engineering for this incredible venture is being carried out here in the UK by engineers at Astrium who are building the structures for two of the spacecraft, as well as all of the propulsion systems.

Jessica Marshall, a systems engineer at Astrium in Stevenage, is in charge of ensuring the UK’s work on the project all goes according to plan.

Marshall started at Astrium in 2006, after studying physics at Birmingham and completing a masters in spacecraft technology at UCL. She says she’s always had an interest in space, but was never really made aware of the opportunities in the sector — despite growing up and going to school a stone’s throw from Astrium’s Stevenage headquarters. ‘I was encouraged to do a physics degree but I was never encouraged to look into engineering, because the teachers at my school didn’t really know what an engineer did.’

It’s easier to remember the one female on the team than it is to remember the 10 different Marks and Daves

Marshall is now at the sharp end of Astrium’s own efforts to address this and regularly visits local schools to talk about the space sector and engineering.

Despite being the only female engineer on her project in the UK, Marshall says she rarely thinks about the gender balance but feels that being in a minority can lead to more recognition. ‘It’s easier to remember the one female on the team than it is to remember the 10 different Marks and Daves, and it can be helpful in that people recognise your face more and the work that you’ve done.’

She believes that one of the keys to encouraging more women into engineering is addressing general perceptions of the role that engineers play. Singling out France, where she says its notable that there are far more female engineers, she says that ‘the total length of time studying very similar to training to be a lawyer or doctor and you are held in very high esteem so it’s a more desirable job in general, which filters through to a healthier gender balance’.

While there are signs that more young women are coming into engineering, Marshall believes the gender imbalance is at its most noticeable further up the career ladder and she thinks that companies need to work hard to address policies that make career progression for women with families difficult

April 1886: the Brunkebergs tunnel

First ever example of a ground source heat pump?