I always find it a little bit odd when commentators refer to robot butlers as a staple of science fiction. I’ve been reading and watching science fiction for over 40 years, and I can’t think of a single example of a robot butler. The closest I can get are the various labour-saving devices invented by Nick Park’s hapless Yorskhire tinkerer Wallace, and frankly nobody sane would actually want any of those anywhere near them.

But there’s clearly a buzz around robots of all types at the moment, with James Dyson’s large invetsment into a robotics lab at Imperial College and Google’s spending spree among the robotics sector. Domestic robots have previously been more the preserve of the Japanese, stemming from concerns about their ageing population — there, the key application is clearly as devices to help elderly and infirm people live independently. In the US and Europe, defence and emergency response applications have led the way. Both types take industrial robots as their starting point. And as we saw in our poll last week, opinions differ about the state of research and where the end-point might be.

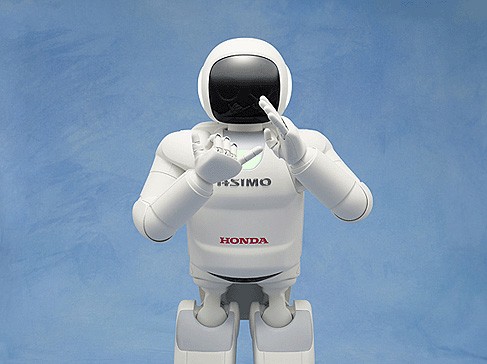

James Dyson thinks we might be ten years off domestic robots. This seems to be very optimistic. Although autonomous robotic vacuum cleaners have been available for some years, they aren’t actually very good at vacuuming (and judging by the internet, are far more useful for taking pets for a ride around the home). The prospect of a single, multi-functional robot home-help seems as far-fetched as ever: homes are designed for humans, so human-like locomotion would be a must, with manipulators that can get into the same position as hands and perform similar functions. We’re a long way away from that, even in the most advanced labs. We’d also need much more advanced machine vision to navigate around and identify things and people. And how would people and machine communicate? By speech? Add a natural language processor and voice synthesiser to the list.

”What would a robot on the battlefield actually do?”

So would we see humanoid robots on the battlefield? The question here must surely be: why would we? Is an upright, bipedal, two-armed robot really the most efficient form for a battlefield? Why devote all those resources to stabilising a top-heavy form when something closer to the ground with more points of contact can get around more easily? And anyway, what would a robot on the battlefield actually do? Interact with humans? Go up against enemy robots? The answers to these questions always seem worryingly vague.

A humanoid search-and-rescue robot makes a bit more sense, for similar reasons to domestic ones — it can access and clear spaces that humans can fit into, opening doors and so on. If something that’s human-shaped and moves like a human can get into a constrained space, then a trapped human can get out.

Ultimately, the multifunctional robot is a bit of a tall order in any case. Industrial robots are successful because they can do essentially one thing very well, over and over again with no variation. Maybe that’s what we should be looking at with domestic robots — lots of small, very limited units, each doing their own thing. But that doesn’t really sound all that useful. In fact, it’s a bit Wallace. And he needed Gromit to clean up after his devices; uncannily intelligent and dextous dogs are even more tricky than robot butlers.

There’s clearly going to be a role for automation at home and in conflict and disaster; probably in hospitals and workplaces as well. But we need to be realistic about what machines can do, why we want them to do these tasks, and how they should do it; and we should also be realistic about what demands we place on technology, considering the actual state of the art. We don’t live in a science-fiction world; and what with most science-fiction worlds being dystopias, we should probably all be very thankful for that.

Red Bull makes hydrogen fuel cell play with AVL

Formula 1 is an anachronistic anomaly where its only cutting edge is in engine development. The rules prohibit any real innovation and there would be...