In the quiet suburbs of Oxfordshire, a small team of engineers may be on the way to achieving what NASA scientists couldn’t - the development of a spaceplane that could reach far into the solar system.

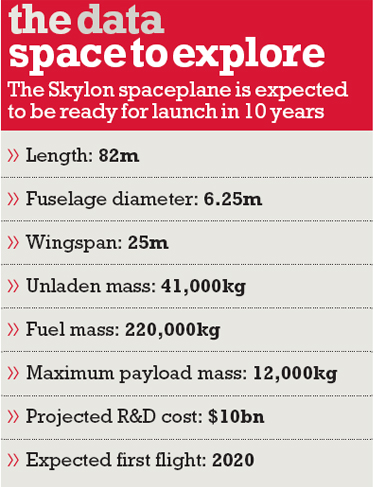

Abingdon-based Reaction Engines has designed the Skylon plane to take payloads - or even passengers - into space from a conventional airport and return them back down to the same runway. The design can carry a 12-tonne payload and could, according to the company, fundamentally change the way we view space travel.

But a spaceplane that can break away from the Earth’s gravitational clutches and return in one piece remains, for many, a near-impossible dream. The European Space Agency (ESA), the Russian Federal Space Agency (RKA) and NASA have poured billions of pounds into single-stage-to-orbit (SSTO) projects and so far none have been successful.

The problem is that the technology to build an SSTO vehicle is extremely challenging, given the huge fuel and power requirements. Rocket-powered vehicles need to achieve a high enough mass ratio to enter orbit and currently the best way to do this is to use the thrust of throwaway rockets, such as the Shuttle’s solid-fuel boosters. However, at around $150m (£96m) per flight in a Shuttle compared with $100,000 in a jumbo jet, the cost of sending even modest numbers of people to space is huge.

Richard Varvill, technical director and one of the founders of Reaction Engines, is adamant that SSTO vehicles could change all that. ’Access to space is extraordinarily expensive, yet there’s no law of physics that says it has to be that way,’ he said. ’We just need to prove it’s viable.’

It is this entrepreneurial attitude that has driven Varvill, along with chief executive Alan Bond and chief engineer John Scott-Scott, to spend 30 years of their lives and more than £20m doing just that.

Their concept for the Skylon is based around a synergistic air-breathing rocket engine (SABRE) that uses jet propulsion to reach the edge of the Earth’s atmosphere before switching to rocket power to get into orbit. The first phase of SABRE requires air from the atmosphere to be cooled before being compressed into the engine and burned with hydrogen, while the second phase draws on liquid hydrogen and a small supply of liquid oxygen to propel the plane into space at speeds of Mach 25.

No one has ever made these heat exchangers at the size, scale and weight that we need to achieveRichard Varvill, Reaction Engines

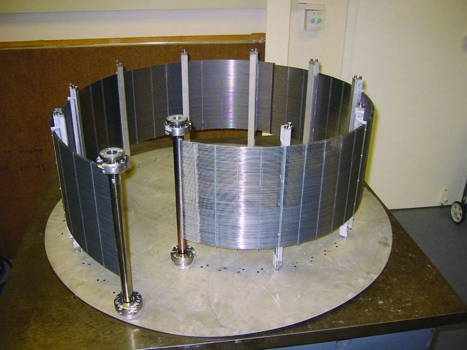

The breakthrough for Reaction Engines has been in the development of its pre-cooler system. At Mach 5, SABRE will need to cope with gases entering at temperatures reaching 1,000 degrees celcius. The pre-cooler uses thousands of small-bore thin-wall tubes, each around the width of a human hair, to drop the air temperature to -150degrees celcius in just 30ms. Back when Skylon was still a concept, the required heat exchangers for this type of pre-cooled jet engine were impossible to make, but with improvements in materials and manufacturing techniques, Varvill believes the technology has turned a corner.

’No one has ever made these heat exchangers at the size, scale and weight that we need to achieve,’ said Varvill. ’We’re attempting do that at the moment and it’s technically very demanding…; If all goes well, we’re hoping to run tests by the middle of next year in front of a Viper jet engine.’ The pre-cooler demonstration technology will be boosted by 1m euros (£817,000) provided by the ESA in February last year to help fund the development programme. Using this money alongside private backing, the team has made huge leaps forward, most notably with its frost-control system.

’A number of years ago, we made a wind tunnel to test the frost-control system, one of the world’s slowest and smallest, and spent four years trying to get it to work,’ he said. ’The problem is that if you don’t do anything about frost, during low altitude atmospheric moisture clogs the matrix and blocks it in about three seconds flat. In the end, we succeeded and now we have a new technology for which there is no precedent.’

Varvill believes the Skylon project is now reaching its final stages. After decades of withdrawn government support and huge technical hurdles, the tide has turned in favour of high-tech manufacturing and, more importantly, human space travel. A recent study into the Skylon’s ability to carry passengers suggests that a trip to orbit in an upright seat, for stays of up to 14 days, would cost around $500,000. Compared with the plans of some groups, Skylon’s space tourism ambitions are still relatively modest. However, the team is also looking to include an upper stage that would move out of low Earth orbit and, if successful, the project could have far wider significance.

You can imagine a situation when some of our industrially important but polluting processes are done in space and the finished products are brought back down to EarthRichard Varvill, Reaction Engines

’The simple truth is that the Earth is part of a much bigger system,’ said Varvill. ’The mineral resources of the solar system exceed that of the Earth by many orders of magnitude. We’re talking a bit of science fiction now, but in theory there’s nothing that stops you going out and enjoying some of that… You can imagine a situation when some of our industrially important but polluting processes are done in space and the finished products are brought back down to Earth.’

After the departure of science minister Lord Drayson, a strong advocate of Skylon, new science minister David Willets looks set to continue supporting the project.’The UK government has changed its attitude to the project enormously in recent years,’ said Varvill. ’That has helped us a lot and lifted our credibility. The financial crash has also helped our case… People are talking about rebalancing the economy and bringing back innovation and manufacturing. And what we’re talking about is the creation of an industry with long-term job opportunities and good export potential.’

Skylon is thought to cost about $10m per flight once development costs have been paid. If all goes to plan, within 10 years the UK could become the first country in the world to launch a single-stage spaceplane in orbit.

Report highlights significant impact of manufacturing on UK economy

I am not convinced that the High Value Manufacturing Centres do anything to improve the manufacturing processes - more to help produce products (using...