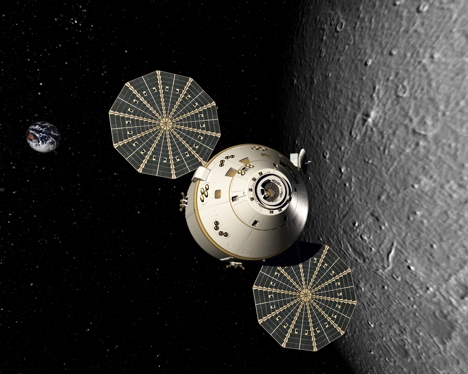

At this week’s ministerial meeting for the European Space Agency (ESA) member states in Naples, science and universities minister David Willetts announced that the UK will contribute to the development of the service module for NASA’s Orion capsule, the manned system the US agency is developing to take astronauts to the International Space Station (ISS) and on future manned missions.

NASA is planning the first Orion trip to the ISS for 2017, and ESA has agreed to develop the service module for the spacecraft from its Automated Transfer Vehicle, the unmanned ‘space truck’ with which it has been resupplying the space station since 2008. This forms ESA’s contribution to the ISS project, which it fulfils ‘in kind’, by developing and supplying equipment and services, rather than financially, for the period 2017–20.

The UK is to contribute €20m (£16m) to the project — the first time it has contributed to manned exploration. This is a one-off payment, Willetts explained, to allow British expertise in propulsion systems and telecommunications to be exploited.

The UK recently boosted its contribution to ESA by 25 per cent, to €1.2bn (£970m) per year, and is expected to increase its involvement in many projects. At the ministerial meeting, Willetts also announced that British scientists and engineers will participate in ESA’s microgravity research programme, known as Elips (European Programme for Life and Physical Sciences). The UK is particularly interested in the Elips projects on how reduced gravity affects the human body, which has implications for research on ageing and on the properties of advanced materials, Willetts said.

Most of the Elips research takes place on the ISS, although experiments are also carried out on sounding rockets, ‘zero-gravity’ aircraft flights and drop towers. The UK will contribute some £3m per year for four years, which will give UK scientists access to these facilities, although the research would still be funded via the Research Councils. ‘They have then got to justify their science in the usual way,’ said UK Space Agency (UKSA) chief executive David Williams.

Further good news for the UK space community came with the confirmation of Russian involvement in ExoMars, the planned project to put a rover onto the red planet to search for signs of organic chemicals associated with past life. The project was in danger earlier this year when NASA pulled its funding, leaving the rover without a rocket to get it to Mars, but its Russian counterpart, Roscosmos, has indicated that it will supply two Proton launchers, the first to take an orbiting satellite to Mars in 2016 to study the Martian atmosphere for signs of methane and other trace gases and the second in 2018 to take the ExoMars rover itself. Contracts are still to be signed, but this is expected by the end of the year.

The UK is a major player in ExoMars, with EADS Astrium building the rover and several British organisations involved in its imaging systems and some of its key sample retrieval and analysis equipment. Willetts also pledged £18m for UK involvement in the Mars Robotic Exploration Preparation Programme, where UK engineers will lead a project to develop nuclear power sources for future space missions; this, according to the UKSA, ‘could potentially demonstrate strong spin-out technology in the terrestrial economy’.

Developing spin-out potential is the goal of another increased investment, with £28m of UK money going into the Generic Support Technology Programme. Designed to take early-phase space research and development into practical application, the programme will help small and medium-sized enterprises and equipment suppliers to develop their technologies up to ESA standards so that they can fly on space missions — an important stage in the process towards commercial exploitation.

JLR teams with Allye Energy on portable battery storage

This illustrates the lengths required to operate electric vehicles in some circumstances. It is just as well few electric Range Rovers will go off...