The vertical graphene flakes, being developed by a team of researchers at Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden, have been shown to kill bacteria on impact, in research published in the journal Advanced Materials Interfaces.

When added to the surface of implants, they could stop bacterial infections during surgery, which in some severe cases can prevent the devices from attaching to the human bone effectively.

Bacteria travel around the body in blood and other fluids, looking for a surface to cling to. Once they find a suitable surface, such as an implant, they start to propagate, forming a biofilm.

But adding a layer of vertical graphene flakes to the surface prevents the bacteria from forming this biofilm, according to Jie Sun, Associate Professor at the Department of Micro Technology and Nanoscience, Chalmers University of Technology.

This could eliminate the need for antibiotics, and reduce the risk of implant rejection.

“The vertical graphene acts like a knife, it will cut into the bacteria and kill it,” said Sun.

The membrane surrounding bacteria has a very strong affinity for graphene, he said. “So the bacteria will attach themselves to the graphene, and then get cut.”

For stability, the spikes are attached to the surface with roots.

Human cells are much larger than bacteria – 25μm in diameter compared to 1μm – meaning they are not damaged by the graphene spikes.

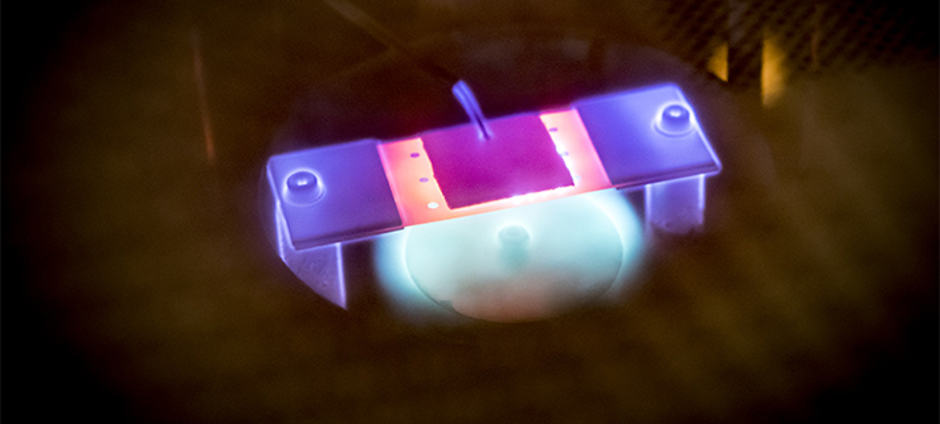

The researchers are now planning further work to make the graphene spikes suitable for use in medical applications. Firstly, the substrate they have been using to grow the graphene is quite small, around 2.5-5cm across, so they plan to increase its size.

They also hope to reduce the cost of the process, said Sun.

“We cannot grow the graphene directly on medical devices, we have to grow it onto our substrate and then transfer it to the devices, and that process is expensive, so we need to reduce that cost,” he said.

Finally, further experiments will be needed to ensure graphene is not harmful to human cells, in the event that a flake were to come loose, he said.

Project to investigate hybrid approach to titanium manufacturing

What is this a hybrid of? Superplastic forming tends to be performed slowly as otherwise the behaviour is the hot creep that typifies hot...