A mildly disgruntled engineer — is there any other kind? — once told me that there was a group of civil engineers in the UK who enjoy unparalleled public goodwill, a high profile and handsome salaries, who are feted in society and even raised to the House of Lords without comment. ‘Of course, they have the good sense not to call themselves engineers,’ he said. ‘They call themselves architects.’

Now, we could argue for years over whether architecture is a branch of engineering. It’s an issue we’ve tackled in this journal, asking the question, who built France’s soaring bridge in the clouds, the Millau Viaduct? Was it Lord Norman Foster, whose name is most often attached to the project, or its impish chief engineer, the less well-known (to the public at least) Michel Virlogeaux?

Elsewhere in the journal, I looked at the Aquatic Centre at London’s Olympic Park, nominated for this year’s Stirling Prize, and the structural engineering that was needed to realise the designs of the architect, Zaha Hadid, after they’d been adapted from a competition entry to a pared-down, cost-controlled version required by straitened economic circumstances. It was a significant challenge to support the soaring winged roof with its dramatic parabolic curves.

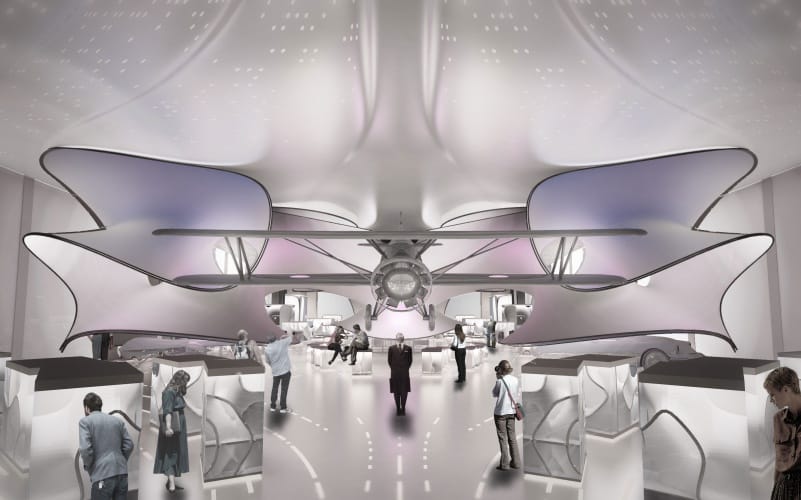

Hadid is, however, one of the most engineering-aligned architects. Trained as a mathematician, her work exemplifies one of my favourite descriptions of architecture — ‘frozen mathematics’. Indeed, her current project is to design the mathematics gallery at London’s Science Museum, whose centrepiece will be a solid representation of the air vortices which form around the wings of a vintage aircraft designed to fly at low velocity.

As an example of the creative possibilities of STEM subjects, Hadid (and other architects who work at a heroic scale) is hard to beat. But a recent event at the Royal Academy of Engineering asked whether engineering should be removed altogether from the STEM acronym, as it downplays the creative aspect of the discipline; something which, it is argued, dissuades many people, notably women and girls, from considering it as a career.

Which is extremely patronising, in my opinion. And if readers will permit another digression in a piece which has already digressed quite a bit (I am conscious of my tendencies as a writer, you see) it downplays the contribution of the figure many claim as the queen of STEM and the figurehead of women in the field, Ada Lovelace, who was honoured yesterday in a day which bears her name.

Ada, the daughter of Lord Byron (although she never knew him), is remembered as the first ever computer programmer, suggesting that Charles Babbage’s proposed mechanical calculating machine, the Analytical Engine, could be used to calculate Bernoulli numbers, a sequence derived from a complex equation involving reciprocals, powers and exponentials.

Ada’s work, published as a series of notes to her translation of an Italian army engineer’s writing about Babbage’s work, could only be a thought experiment: the Analytical Engine, a development of the earlier and more famous Difference Engine with separate processing and memory units, was never actually built because the notoriously prickly and obsessive Babbage insisted on learning watchmaking and machining skills himself and ran out of money, time and life.

So Ada’s feat of inventing the concept of computer programming could only have been one of pure creativity. Nobody had done it before or even could have; there was no precedent even for the frame of reference. So although it was underpinned by her deep knowledge of mathematics — in which she’d been trained at the insistence of her mother, to rid her of her father’s ‘unhealthy’ poetic outlook — the act that raised her to STEM immortality was one of pure creativity (and maybe proof that you can’t extinguish poetry, you can just divert it). Bringing my digression full circle (I don’t ramble completely aimlessly), one could say much the same about Zaha Hadid’s designs; and if you visit her new gallery at the Science Museum, be sure to go downstairs and look at the reconstruction of the Difference Engine.

So to say that the E should be taken out of STEM because it isn’t creative enough is to misunderstand the history and the whole basis of engineering. It’s inherently creative; using a knowledge of physical science and its mathematical underpinning to create solutions to problems, new concepts, and solid reality that can span a gorge above the clouds or create a building you can go swimming in. As to whether architecture is engineering, I think that varies from architect to architect, but it’s certainly a cause of engineering and one of the most important ways that engineering becomes visible and exerts its influence on the world.

To conclude this mass of digression, if STEM doesn’t seem creative, it’s not an inherent fault in the subject. It’s the fault of whoever’s explaining it.

Project to investigate hybrid approach to titanium manufacturing

What is this a hybrid of? Superplastic forming tends to be performed slowly as otherwise the behaviour is the hot creep that typifies hot...