Held to celebrate the achievements of the 19th century and usher in those of the 20th, the event saw the public introduced to iconic inventions such as the diesel engine, as well as cultural developments such as talking films.

But while the show’s legacy helped shape history, its beginnings were altogether more inauspicious. When the show opened in April 1900 it was beset by problems, many of which had their origins in the run-up to the event. According to The Engineer, several of the temporary buildings due to be constructed for the fair were behind schedule, owing to a shortage of rolled iron.

Exactly who was responsible for the shortfall was unclear, with blame being passed along the supply chain. “Ironmasters were unable to supply what was needed because they could not get pig iron,” wrote our predecessors. “The blast furnace proprietors threw the blame on the coke oven owners, and these shifted the burden of complaint on to the shoulders of the colliery companies.” Plus ça change.

Gigantic cranes were swinging around, timbers were being knocked down from scaffolding, and ropes and planks formed a trap for the unwary

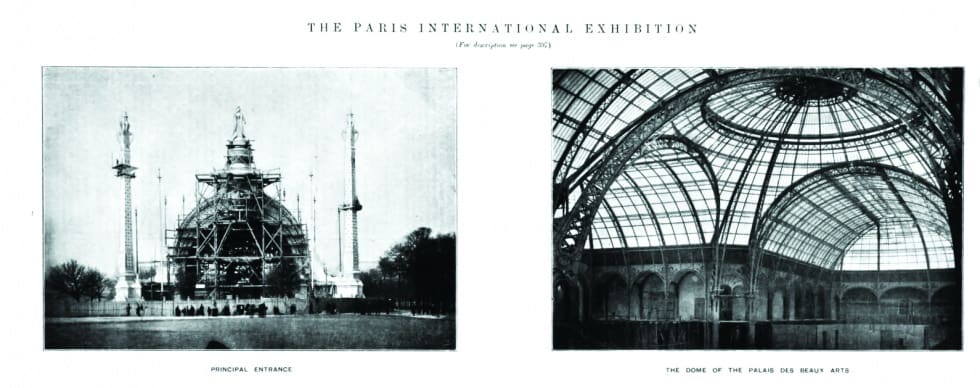

Instead of the buildings being completed by the end of 1899, they were still receiving their final touches on the eve of the event. In fact, The Engineer reported that on the day before the formal opening it was doubtful it would be possible to admit the public. “The grounds were a perfect chaos: the various halls were encumbered with enormous piles of bales and packages, and empty crates and boxes obstructed the entrances. Gigantic cranes were swinging around, timbers were being knocked down from scaffolding, and ropes and planks formed a trap for the unwary.”

In an attempt to restore some kind of order to the madness, 1,500 soldiers were drafted in to help clear away empty cases, clean up the halls, and make the outside walks presentable. By the time the general public was admitted on Sunday 15 April, the exterior of the exhibition buildings were reportedly in good shape, but there was little to be seen inside.

On arriving into the Vincennes annexe in east Paris via the main entrance, one was confronted with the US machinery hall. Despite the “vigorous efforts” being made by the US to build up a big trade of machine tools with France, only two or three firms had their stands in “anything like order” as the fair got underway. These included the Ingersoll-Sergeant Drill Company of New York, and the Shaw Electric Crane Company of Muskegon, Michigan. Elsewhere, preparations appear to have gone more smoothly in the vast hall with railway rolling stock on display. “Already German four-cylinder locomotives of 70 tons are to be seen in juxtaposition with Hungarian engines and passenger carriages,” wrote The Engineer, “and a light locomotive, in which steam is raised by petroleum, constructed in Switzerland for the Ethiopian railways.”

The Paris Exhibition was also the ideal platform to showcase the motor car, which had come to wide public attention with Karl Benz’s Patent-Motorwagen in 1886. The technology’s increasing popularity in the intervening period led car manufacturers to demand the vehicles be given special preference in the Champ de Mars exhibit just south of the Eiffel Tower, rather than in the relative obscurity of the Bois de Vincennes.

At one point, the dispute with the organisers looked like boiling over, with manufacturers threatening to abstain from the exhibition, or even hold a show of their own. “Up to the very last moment… the leading motor car builders neglected to send in applications for space,” said The Engineer, “and it was only when the time for sending in entries was extended that they finally decided to take part in the Vincennes display.”

Unsurprisingly given the circumstances, the automobile halls were among the least populated at the outset of the exposition. Accommodation for 400 cars had been set aside, but only 30 were reported as being ready for the opening, and not a single one had yet put in an appearance.

It’s a far cry from the recent Geneva Motor Show, which had its humble beginnings just a few years later in 1905. The 2016 edition saw over 200 exhibitors and countless individual models. An indication, if indeed one was needed, that the Paris Exhibition truly did herald the age of the automobile.

Red Bull makes hydrogen fuel cell play with AVL

Formula 1 is an anachronistic anomaly where its only cutting edge is in engine development. The rules prohibit any real innovation and there would be...