Danielle George MBE is a Professor of Radio Frequency Engineering at the University of Manchester. She delivered this year’s Institution of Engineering and Technology (IET) Appleton Lecture, “Smart Machines and Data: From ALMA to Zetabytes”, on 19th January 2017.

Danielle George MBE is a Professor of Radio Frequency Engineering at the University of Manchester. She delivered this year’s Institution of Engineering and Technology (IET) Appleton Lecture, “Smart Machines and Data: From ALMA to Zetabytes”, on 19th January 2017.

We have lost something in the current education system – what we call the ‘art of tinkering’.

I don’t fully understand why this is the case, but it is at least partly to do with a lack of confidence from parents and teachers, a perception that science and maths is hard, and a fear of failure.

In schools – and we are seeking a knock-on effect in the make-up of university applicants – there is no incentive to just be curious for the sake of being curious and experiment. The ‘hey, how does that work?’ mentality is missing.

There is no room in the curriculum for it, and we need to instil this at primary school, even at nursery level, and allow children to be curious with their teachers, parents and grandparents.

It is also because we take many of the machines that run our lives so efficiently for granted. People used to tinker with cars a lot more than they do now, as we tend now to take them to a garage. But going back only a few years most people knew how to change oil and tyres.

However, this mentality in young people - a mentality not helped in any way, shape or form by our current education system - must change.

Here is an example of why change is needed. I am UK lead on the Atacama Large Millimetre Array (ALMA). When completed, ALMA will provide unprecedented insight into star formation during the early universe and provide the most detailed maps of star and planet formation.

I am also involved in the Square Kilometre Array (SKA), whose size will make it 50 times more sensitive than any other radio instrument currently in existence. The dishes alone will generate ten times the current global Internet traffic.

These developments provide huge challenges, such as collecting the data in the first place, of course. And then when we have all the data, where do we store it? But these are going to be questions for our children and grandchildren.

We therefore need to show that it isn't such a big step between having fun in your bedroom, garage, or garden shed, and solving the ‘grand challenges’ that exist in the world today. And we need the next generation to solve these challenges through engineering.

From nursery, I was always questioning things. My parents never said, 'Oh, I don't know'. If they didn't know - and a lot of times they didn't - then they would buy me a book or talk to the teacher and say, 'Danielle has been asking about this – where could we find some information about it?'. That encouragement was key. As educators we must provide this encouragement to young people, curriculum permitting or not.

This is the perfect time to take a step back and ask ourselves what we are really doing to inspire curiosity. The current generation is growing up with technology, skilled with a mobile phone from the age of two. We have coding in schools, and in higher education, low-cost electronics enable us to support a desire to take them apart and find new uses for them.

Tinkering School (Credit: Julie Spiegler)

Tinkering School (Credit: Julie Spiegler)We need to make sure – as parents, teachers and the public – that we don't segregate children. For example, in a playgroup where you have Lego in one corner, and all the boys go there, and dolls in the other corner, and all the girls go there. If that is their preference, fine, but we shouldn't influence them; we should encourage them to play with whatever they like.

We also have an obligation to encourage greater social status for engineers. In Germany, if you are an engineer you are very well respected as a professional in the same way as a lawyer or a medical doctor is. In the UK, this is not the case.

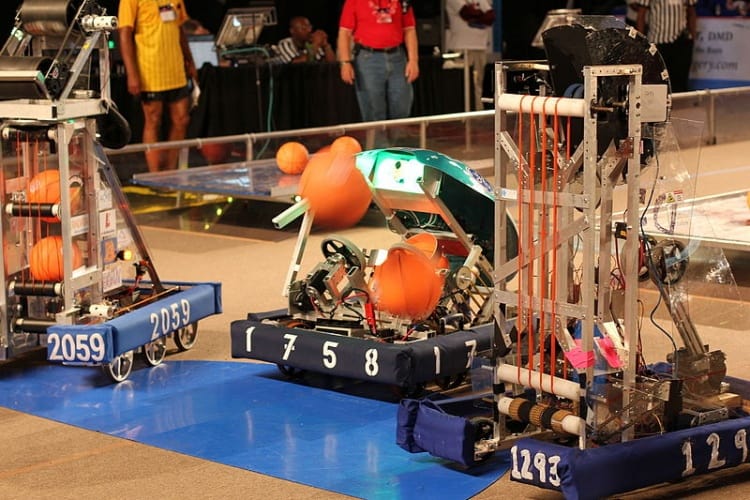

The ‘maker movement’ shows that creativity, playfulness and ingenuity can fuel STEM learning, and many countries take this to the next level to bridge the gap between extra-curricular and the education system. The Tinkering School in the USA is a good example. They give children real tools to solve real problems. By learning through doing, we strive to make mistakes and learn from them.

Report highlights significant impact of manufacturing on UK economy

I am not convinced that the High Value Manufacturing Centres do anything to improve the manufacturing processes - more to help produce products (using...