Scientists have been trying to develop so-called yolk-shell catalysts as a means of imparting greater selectivity on heterogeneous catalysis, a process used in most industrial chemistry, including the manufacture of fine chemicals, petrochemicals and agrochemicals.

Boston College assistant professor of chemistry Chia-Kuang Tsung and his team have developed a nanostructure that can regulate chemical reactions due to a thin, porous skin capable of precisely filtering molecules based on their size or chemical make-up, the group reported recently in the Journal of the American Chemical Society.

‘The idea is to make a smarter catalyst,’ said Tsung in a statement. ‘To do that, we placed a layer of “skin” on the surface that can discriminate between which chemical reacts or does not react with the catalyst.’

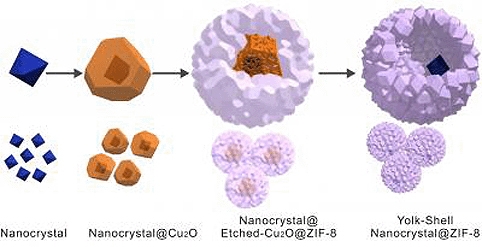

The team started with a nanoscale metallic crystal, then applied a ‘sacrificial layer’ of copper oxide over it, Tsung said.

Next, a shell of highly refined material known as a metal-organic framework (MOF), was applied to the structure. Immediately, the polycrystalline MOF adhered to the cooper oxide, forming an outer layer of porous ‘skin’.

Simultaneously, the MOF began to etch away the copper oxide layer from the surface of the crystal, creating a tiny chamber between the skin and the catalyst where the chemical reaction can take place.

Testing the structure with gases of varying molecular structure, Tsung said the skin proved it could allow ethylene to pass through and reach the catalyst. The gas cyclooctene, with larger molecule size, was effectively blocked from reaching the catalyst. Tests showed the central difference between the new method and earlier incarnations of yolk-shell catalysts was the creation of the empty chamber between the skin and catalyst, the researchers reported.

Tsung said the level of control is a significant step in the use of nanoscale chemical structures in the effort to impart greater selectivity and control on heterogeneous catalysis, a proven process used to create chemicals in nearly all areas outside of pharmaceutical research, which employs homogeneous catalysis.

Scientists have been looking for ways to exert greater selectivity in heterogeneous catalysis in an effort to expand its application and extend ‘green chemistry’ benefits of reduced by-products and waste, Tsung said.

The key to the nanocrystal is the extremely precise structure of the metal-organic framework, Tsung said, which gives the skin an intricate network of pore-like passages through which select gases or liquids can pass before contacting the catalyst and triggering the desired reaction.

‘We can make these pores very precisely, just like your skin or like the membrane surrounding a cell,’ Tsung said. ‘We can change their composition and chemical properties in order to accept or reject certain types of reactions. That is a level of control chemists in a variety of fields are eager to see nurtured and refined.’

Viking Link connects UK and Danish grids

These underwater links must, based on experience with gas pipelines, be vulnerable to sabotage by hostile powers. Excessive dependency on them could...