The RNLI has been saving an average of 722 lives a year since its founding as the Royal National Institution for the Preservation of Lives and Property from Shipwreck in 1824. The organisation currently operates a fleet of over 400 vessels that are categorised as high-speed all-weather lifeboats (ALBs) and equally nimble inshore lifeboats. The Shannon Class lifeboat was the latest to join RNLI’s fleet, boasting a top speed of 25 knots that is abetted by its two 13l Scania D13 650hp engines and twin Hamilton HJ364 waterjets.

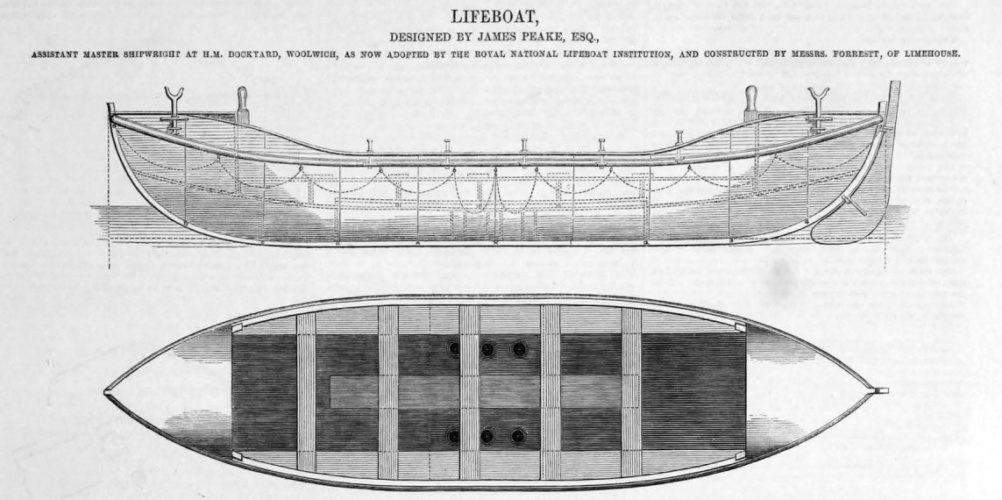

In 1856, a full 34 years before the first steam-driven lifeboat was brought into service, The Engineer described a design by James Peake that relied on the brute force of oarsmen for propulsion and an improved function that has long been standard on ALBs, namely the ability to self-right.

“This property, which has been considered indispensable by reason of the awful accidents which have occurred, is secured to the boats by two qualities acting in conjunction,” our Victorian predecessor noted. “First, the raised ends at the extremes, or the bows and stern, are made into air-tight cases, and give a displacement to the thwarts when the boat is bottom upwards, equal to the weight of the boat. Second, the iron keel, of 7cwt. The boat when bottom upwards…would be, by the centre of the weights of her being above the centre of the supporting water, in a state of instability – the centre of gravity being above the sustaining points of support afforded by the raised air cases. The result of such a position is known to most people, being such that the least deviation from the upright causes the iron keel to press downward, and the buoyancy of the raised air cases to act in full force upwards to make the boat assume the upright position. This evolution seldom exceeds three seconds.”

READ THE ENGINEER'S 1856 ARTICLE ON PEAKE'S LIFEBOAT

Peake’s lifeboat was 30’ long and had an extreme breadth of 7’6”, giving the lifeboat a breadth to length ratio of one to four. The Engineer noted that Peake’s boat produced the ‘least possible draught of water with the greatest stability’. “Hollow water lines or level lines have been avoided in the construction of these boats as much as possible; the hollow water line for a boat propelled by oars being considered detrimental to velocity,” The Engineer said.

Extra buoyancy provided by air cases would have little effect without relieving tubes and valves that passed through the water-tight deck and bottom of the boat. “These tubes are 6” in diameter, and six in number; through these the water received into the internal space of the boat up to the gunwale rushes out by the lifting power of the boat and the immersed air cases; and it has been found, that on an average, the six valves will clear the boat, when full to the gunwale, in thirty seconds, the valves opening downwards only,” The Engineer said.

During the year 1854 our coasts were the scene of no fewer than 987 wrecks of ships

“The great need of such lifeboats as that which we have described is rendered manifest by a glance at the Admiralty Register of Wrecks and at the Wreck Chart of the British Isles, which is annually published by order of the House of Commons,” The Engineer observed. “During the year 1854 our coasts were the scene of no fewer than 987 wrecks of ships; of which 431 were totally lost as wrecks, and 53 sunk by collision; in the remaining 503 cases, the ships, either by stranding or by collision, were so much damaged as to require to discharge cargo. But, more melancholy to tell, there are believed to have been the fearful number of 1,549 human lives lost by these catastrophes - and all, be it remembered, on our own coasts - on the coasts of the most busy maritime island in the world: when, if there be liability of disaster through the vast congregation of shipping, there ought on the other hand to be a supply of invention and good sense sufficient to check, in same degree, such disasters.”

The Engineer went on to state that, despite these calamities, 132 people were saved by the RNLI in 1854. Twenty to thirty of Peake’s boats were built and the RNLI ‘adopted them to the exclusion of others built from different designs.’

Swiss geoengineering start-up targets methane removal

No mention whatsoever about the effect of increased methane levels/iron chloride in the ocean on the pH and chemical properties of the ocean - are we...