The Engineer’s annual review of technological advances took a melancholic turn in January 1940 when it became clear that aeronautical innovation would be driven by conflict.

Four months had elapsed since Britain and France declared war on Germany, yet it was becoming apparent that fighters and bombers would be more pivotal to the outcome of the Second World War than the First World War.

As noted in 1940, great strides had been made to “knit the world together by rapid air transport” in the 36 years since the Wrights first flew, but military advances continued to outpace those in the civilian sector.

“It is always so with new inventions,” The Engineer wrote with resignation. “Mankind, still in the youth of his civilisation, is quick to seize on a chance to design yet another tool for attack on his neighbours, and only gradually is the peaceful use of the device discovered and developed.”

The author couldn’t have predicted that by July 1940, an entirely new theatre of war would have opened up in the skies above England that would be followed by a devastating – and strategically futile – bombing campaign by the Luftwaffe. That said, our correspondent went on to exercise a degree of prescience in assessing what might be required to defend our shores.

With only a narrow window through which to observe the war, The Engineer noted that results were going against Germany with “certainly no less than 25, and maybe nearer 50 per cent” losses for the Luftwaffe.

“The formations concerned in the fighting so far have all been small, and the question may be asked whether the bombers would find greater security if they came in large formations,” The Engineer wrote.

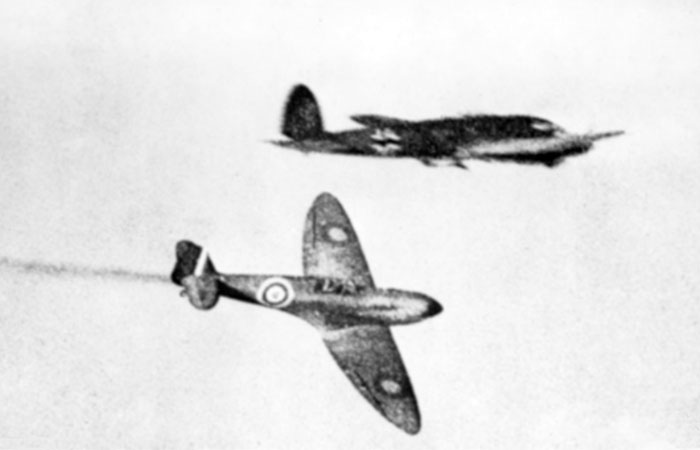

Bombers had range but they lacked the speed and manoeuvrability to outrun or out-manoeuvre fighters sent to repel attacks, but that didn’t stop The Engineer observing that “the initiative is always with the attacker, and until one can be quite sure that every possible mode of attack has been measured up and allowed for it is not possible to say that the defence is complete”.

Our correspondent said: “At present the nature of the attack depends on the speeds and manoeuvring powers attainable today, but it is necessary when planning the defence to look far ahead. The speeds are now well over 300mph and machines have even been driven at over 400mph; it must be expected that they will rise still further, though to pass Nature’s steep barrier at the velocity of sound will take much more knowledge than anyone in the world now possesses.

“Fortunately, there is good reason to expect that fighting aircraft will always have a comfortable margin of speed over contemporary bombers.”

Bomber designers were, said The Engineer, continually trying to push the performance of their aircraft in terms of speed, but realised that the omission of guns would leave their lumbering aircraft vulnerable to attack.

“As a gun platform the fighter is a much better proposition,” our correspondent noted. “Better as regards accuracy, and better as regards volume of fire. No doubt it is due in part to these causes that the casualty list among German aeroplanes has been so considerable.”

As if predicting a significant operational failing of the Luftwaffe during the Battle of Britain, our correspondent observed that bomber formations need the protection of accompanying fighters, but “the latter lack the range of the large bomber, and the home-based defensive fighters are vastly better circumstanced. This is to the good as it strengthens the defence”.

“On the whole, therefore, it can be said that the defence in the air is now exceedingly powerful and is likely to grow still stronger,” said The Engineer. “Defence from the ground is also becoming increasingly effective and is fully keeping pace with technical improvements in aircraft, whilst the arrival of hostile aircraft in huge formations would naturally delight the aircraft gunner’s professional eye.”

Our reporter said: “It is sad that our aeronautical record of 1939 should have to relate to warlike matters entirely. But the requirements of public safety make it undesirable that the scientific advances of the year, important as they are and interesting as they would be to our readers, should be disclosed at this time. We hope for better fortune when ‘Aeronautics in 1940’ comes to be written.”

Project to investigate hybrid approach to titanium manufacturing

What is this a hybrid of? Superplastic forming tends to be performed slowly as otherwise the behaviour is the hot creep that typifies hot...