The approach from a team at the University of Wisconsin-Madison may be useful in applications where traditional temperature probes will not work, like monitoring semiconductor performance or next-generation nuclear reactors.

Stealth sheet cloaks heat signature of people and vehicles

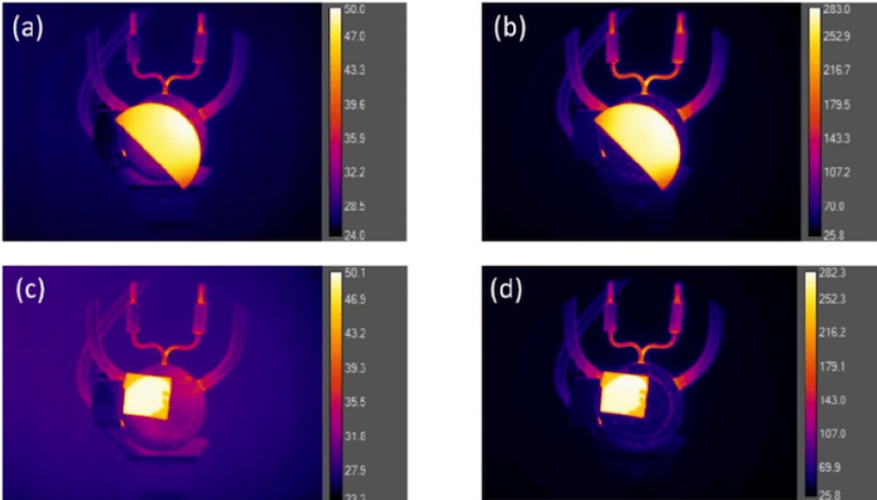

Many temperature sensors measure thermal radiation, most of which is in the infrared spectrum, coming off the surface of an object. The hotter the object, the more radiation it emits, which is the basis for devices like thermal imaging cameras.

According to UW-Madison, depth thermography goes beyond the surface and works with a certain class of materials that are partially transparent to infrared radiation.

"We can measure the spectrum of thermal radiation emitted from the object and use a sophisticated algorithm to infer the temperature not just on the surface, but also underneath the surface, tens to hundreds of microns in," said Mikhail Kats, a UW-Madison professor of electrical and computer engineering. "We're able to do that precisely and accurately, at least in some instances."

Kats, his research associate Yuzhe Xiao and colleagues described the technique in ACS Photonics.

For the project, the team heated a piece of fused silica and analysed it with a spectrometer. They then measured temperature readings from various depths of the sample using computational tools previously developed by Xiao in which he calculated the thermal radiation given off from objects composed of multiple materials. Working backwards, they used the algorithm to determine the temperature gradient that best fit the experimental results.

Kats said this particular effort was a proof of concept. In future work, he hopes to apply the technique to more complicated multilayer materials and expects to apply machine learning techniques to improve the process. Eventually, Kats wants to use depth thermography to measure semiconductor devices to gain insights into their temperature distributions as they operate.

It is claimed that this type of 3D temperature profiling could also be used to measure and map clouds of high temperature gases and liquids.

"For example, we anticipate relevance to molten-salt nuclear reactors, where you want to know what's going on in terms of temperature of the salt throughout the volume," Kats said in a statement. "You want to do it without sticking in temperature probes that may not survive at 700oC for very long."

He also said the depth thermography technique could aid in measuring the thermal conductivity and optical properties of materials without the need to attach temperature probes.

"This is a completely remote, non-contact way of measuring the thermal properties of materials in a way that you couldn't do before," Kats said.

Nanogenerator consumes CO2 to generate electricity

Whoopee, they've solved how to keep a light on but not a lot else.