The microfluidic device, described in the 17 March online edition of the journal Small, could allow doctors to quickly determine whether cancer has spread from its original site. It could also be used to detect viruses such as HIV.

It could eventually be developed into low-cost tests for doctors to use in developing countries where expensive diagnostic equipment is hard to come by, said Mehmet Toner, professor of biomedical engineering at Harvard Medical School.

Toner built a version of the device four years ago. In that version, blood taken from a patient flows past silicon posts coated with antibodies that stick to tumour cells. Any cancer cells that touch the posts become trapped although some of the cells might not encounter the posts at all.

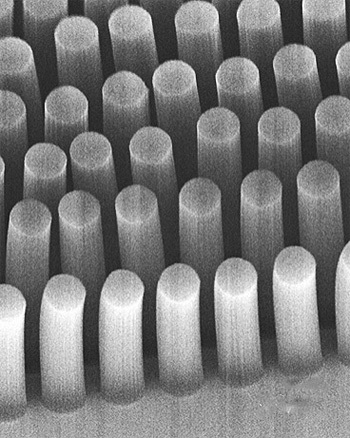

Toner believed that if the posts were porous, cells could flow right through them, making it more likely they would stick. To achieve that, he enlisted Brian Wardle, an MIT associate professor of aeronautics and astronautics, who often utilises carbon nanotubes when designing advanced materials.

The new microfluidic device is studded with carbon nanotubes, which are claimed to collect cancer cells eight times better than the original version.

Assemblies of the tubes are highly porous; a forest of carbon nanotubes, which contains 10 billion to 100 billion carbon nanotubes per square centimetre, is less than one per cent carbon and 99 per cent air, leaving room for fluid to flow through.

The MIT/Harvard team placed various geometries of carbon nanotube forest into the microfluidic device.

As in the original device, the surface of each tube can be coated with antibodies specific to cancer cells. However, because the fluid can go through the forest geometries, as well as around them, there is much greater opportunity for the target cells or particles to get caught.

The researchers can customise the device by attaching different antibodies to the nanotubes’ surfaces. Changing the spacing between the nanotube geometric features also allows them to capture different-sized objects — from tumour cells, about a micron in diameter, down to viruses, which are 40nm.

The researchers are now beginning to work on tailoring the device for HIV diagnosis. Toner’s original cancer-cell-detecting device is now being tested in several hospitals and may be commercially available within the next few years.

Glasgow trial explores AR cues for autonomous road safety

They've ploughed into a few vulnerable road users in the past. Making that less likely will make it spectacularly easy to stop the traffic for...