Birmingham engineers are developing a technique designed to make microsurgery more accurate by taking real-time force and torque measurements during operations.

The team at Aston University’s School of Engineering and Applied Science hopes a robot-controlled drill incorporating the new sensor-based technology will be used for the first time in a delicate ear operation early next year.

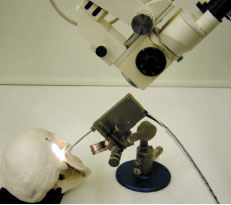

The technique being developed for the cochleostomy procedure uses a unique sensory-guided robot that can accurately penetrate through tissue and, through an inference process, know when to stop drilling by measuring the various forces present at the front of the drill.

Technical leader of the project, Prof Peter Brett, said the procedure uses sensory data gathered during surgery to measure changes in force and torque on the drill as tissue is removed. Force and torque operate in opposite ways as the surgical drill nears the breakthrough point; torque increases markedly, while force decreases as the bone thins out in front of the drill bit.

In the operation, which Brett said will take place in January or February, the device will penetrate the cochlear wall, inside of which is a membrane. The robot will use the sensor system to detect the location of the membrane and stop drilling. This is important, Brett added, because a high level of sterility is maintained by not penetrating the membrane.

Conventional robotic systems use pre-operative scanned data. This is problematic when it comes to microsurgery, because applying a drill to small structures and fibres disrupts and distorts the original patterns taken with pre-operative scanning. By moving the structure, the plan drawn up around the scan can be rendered useless.

‘We are looking at real-time sensory information, using information rather than pre-scanned data,’ said Brett. ‘The process of sending actuation to guide a robot device up to an interface has never been attempted before, but it is much more accurate than a manual effort — in terms of accuracy, we are talking microns.’

The drill is the flagship application for this technology, but the team is looking to apply the smart sensor technology into other medical fields where accuracy is paramount and guiding machines with information could be used, such as endoscopes and catheters.

The EPSRC and Birmingham NHS Trust are funding the project over three years. The Aston team also plans to establish a network of clinicians and academics to explore possible uses of microsurgery tools at a cellular level.

Glasgow trial explores AR cues for autonomous road safety

They've ploughed into a few vulnerable road users in the past. Making that less likely will make it spectacularly easy to stop the traffic for...