Water contributes to concrete degradation on its own, and can also carry chemicals such as salt that have an additional corroding effect. Monitoring how water penetrates concrete is, therefore, essential for overseeing the health of the built environment, and the material’s ubiquity makes this a significant task.

"When we think about construction - from bridges and skyscrapers to nuclear plants and dams - they all rely on concrete," says Mohammad Pour-Ghaz, an assistant professor of civil, construction and environmental engineering at North Carolina State University.

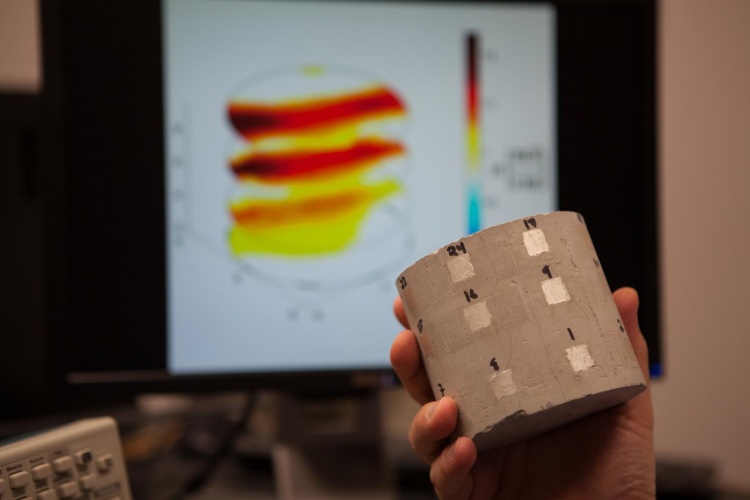

The electrical imaging technique developed by Pour-Ghaz and his colleagues involves placing electrodes around the perimeter of a structure. A computer program then runs a small current between two of the electrodes at a time, cycling through a number of possible electrode combinations.

Each time the current runs between two electrodes, a computer monitors and records the electrical potential at all of the electrodes on the structure. Custom software then computes the changes in conductivity and produces a three-dimensional image of the water in the concrete.

"We have developed a technology that allows us to identify and track water movement in concrete using a small current of electricity that is faster, safer and less expensive than existing technologies - and is also more accurate when monitoring large samples, such as structures," said Pour-Ghaz.

"The technology can not only determine where and whether water is infiltrating concrete, but how fast it is moving, how much water there is, and how existing cracks or damage are influencing the movement of the water."

Existing methods of mapping water in concrete use X-rays or neutron radiation, but these are limited in scope. The prototype built by the researchers has already captured images from structures too big to be analysed with these older techniques, and the team is now looking to build on this success.

"Our electrical imaging technology is ready to be packaged and commercialised for laboratory use, and we'd also be willing to work with the private sector to scale this up for use as an on-site tool to assess the integrity of structures," said Pour-Ghaz.

Project to investigate hybrid approach to titanium manufacturing

What is this a hybrid of? Superplastic forming tends to be performed slowly as otherwise the behaviour is the hot creep that typifies hot...