War has driven some of our biggest technological leaps. If only we could innovate with such purpose and drive in peacetime we might just solve all the world's problems, writes our anonymous blogger.

War has driven some of our biggest technological leaps. If only we could innovate with such purpose and drive in peacetime we might just solve all the world's problems, writes our anonymous blogger.

It is no more than coincidence that my date for the submission of November's piece falls close to Remembrance Day, but this results in it being a revisited inspiration. I have considered whether I should actively avoid it this year but the thoughts and questions that lead from the contemplation of war and loss is, perversely, such fertile ground that I have at least decided to keep with it for now.

Engineering could possibly lay claim to being the profession with the closest link to warfare, beyond the armed forces themselves. You could argue that throwing rocks and sticks is merely the application of our innate ability to use our environment. However, when our ancestors first selected a tool, and then used it to sharpen one of those sticks; they stepped onto the first rung of the armaments engineering ladder.

There are plenty of civilian led advances but the acceleration of our level of technical sophistication during times of war is notable

Sadly it is the nature of humanity to use weapons to assert their dominance, also establishing a need to defend. A stalemate creates the conditions for further developments, which then have to be countered in turn. Situations with an imbalance of power coupled to mobility go further and lead to the creation of empires. Of course technology does not produce empires alone but it is a key part. Roman tactics and political will would have achieved very little without the short sword and roads. Would England ever have been more than a damp little island above Europe without superior arms and shipping?

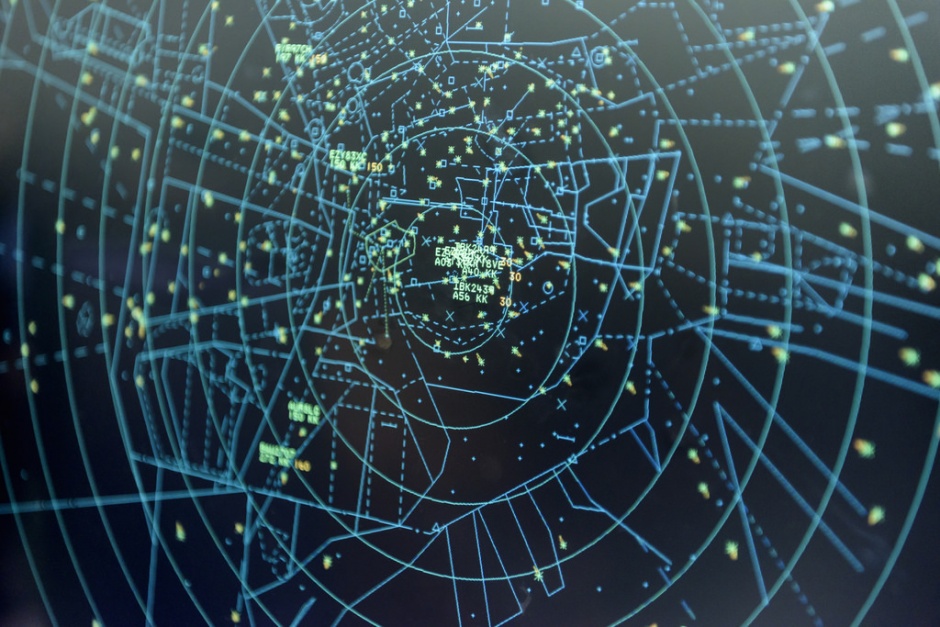

A lot of military led developments have gone on to benefit mankind in a wider context. Flying in your jet powered aircraft, kept safe by radar informed air traffic control, at high subsonic speeds is testament to this. Who can say if, in a purely civilian world, we would have had them anyway; but the fact remains they were born of the near constant state of being in an armaments race. There are also plenty of civilian led advances but the necessary acceleration of our level of technical sophistication during times of war is notable.

It may be naïve and unrealistic but there is something incredibly uplifting about the belief that the continued arc of research and investment will cure all the world's problems

I suspect that the classic triangle of cost/quality/time provides the answer. It is a basic tenet that you can only ever achieve two of the three. If you are in a war with a roughly equal enemy then you do not have the luxury of compromising on either delivery dates or quality. You need better weapons than your enemy and you need them immediately. Therefore you are compelled to spend the money to get them.

Come peacetime, largely free of either “hot” or “cold” wars, and the use of money to advance science and technology is questioned. The impetus changes from the preservation of freedom or ideology and focuses instead on the protection of wealth. I do not know how this can be changed, or even if it can be, but I feel failed by the optimism shown immediately after the first and second world wars.

Looking at the popular culture of the 1920's and 1950's you see a hope that the strides made forward in the sciences will continue. It may be naïve and unrealistic but there is something incredibly uplifting about the belief that the continued arc of research and investment will cure all the world's problems. A lack of hunger and disease along with the provision of a comfortable life for all may bring its own concerns but without the pressures of noted inequalities across the globe in these respects, surely the drive for conflict would be reduced?

Utopia may be unobtainable but while that most selfish act “self-preservation” can lead to the advancement of human-kind as a whole it seems that when we can look at investing in the wider vision we become more insular. One man notably bucked this trend and saw his inventions as being for the betterment of all, to his own detriment. Yet, as is the way, he was to be eclipsed by those who sought to build empires and accrue wealth instead. The engineer's contribution to a world without wars surely lies within what he does in peacetime and for that he or she need look no further for a role model than Nikola Tesla.

You can read about some of Tesla's contributions to the engineering of electricity generation and distribution in this feature from our 160th anniversary supplement.

Red Bull makes hydrogen fuel cell play with AVL

Surely EVs are the best solution for motor sports and for weight / performance dispense with the battery altogether by introducing paired conductors...