A Liverpool-based SME is leaving traditional supercar manufacturers in its wake. Andrew Wade reports

As the director of product development behind the car with the second fastest Top Gear lap ever, you would expect BAC co-founder Neill Briggs to be happy about the achievement. And he is. But he’s also slightly irked by the fact that his company’s BAC Mono was kept off the top spot by a Pagani Huayra suspected of running on modified slicks, contravening the Top Gear rules.

“We say we’re the fastest on road-legal tyres,” said Briggs. “You can make your own mind up about what Pagani did. If you search online you can read all about that.”

Rather than dwelling on what the £1m Huayra may or may not have done, Briggs prefers to focus on the Mono, whose entry price happens to be a comparatively meagre £125,000. With that sort of gulf, it’s incredible that the Liverpool-based company is able to compete with those such as Pagani, not to mention leaving other supercar manufacturers in the dust.

“To put it into perspective, we’re five seconds quicker than a Ferrari Enzo and we’re six seconds quicker than a Porsche Carrera GT,” according to Briggs.

These are giants of the motoring world, and a Liverpool SME set up by two local lads is eating them for breakfast. Founded in 2009 by Neill and his brother Ian, Briggs Automotive Company has become one of the most intriguing success stories of UK engineering.

Neill is an engineer with experience working at both Bentley and Ford, playing a key role in the development of the latter’s Focus RS. His brother Ian is BAC’s design director, and has previously worked on luxury yachts and the Airbus A380 fleet, as well as with OEMs such as Porsche, Mercedes and Audi. They’ve combined their expertise to create a car that gained almost instant cult status, an automotive experience they say is truly unique.

“Obviously the first thing that sets us apart is the fact that we’re the first and only road-legal single-seater car in the world,” Briggs said. “We’ve redefined what we call a niche within a niche, which is the purist supercar sector.

“We identified this trend when we started the project in 2007, and we asked how would a car look if it wasn’t based on a concept that in essence was a slightly flawed or compromised concept of transportation – moving two people around, and luggage and golf clubs and all the rest of it.”

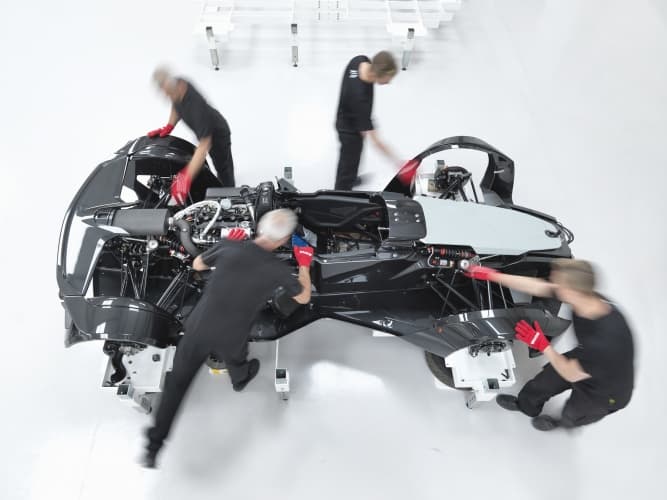

The result is a beautifully crafted machine that resembles a Formula car, but with enclosed wheels and other design details that make it perfectly legal to drive on UK roads. Although perhaps more at home on the track (particularly with the combination of British weather and the vehicle’s open cockpit), BAC has found that around 70 per cent of its customers use the Mono on the road at some point.

When it launched in 2011 the car’s 2.3-litre Cosworth engine – combined with a kerbweight of just 540kg – produced a top speed of 170mph, the 280bhp taking you from 0-60mph in 2.8 seconds. Numbers like that, in tandem with a much lauded gearbox and precise handling aided by the longitudinal placement of the engine block, led to the Mono being named The Stig’s car of the year for 2011.

“It’s a great accolade because it’s something they’ve never repeated on Top Gear,” said Briggs.

By 2013, when the Mono debuted on the Top Gear track, BAC had just six employees. That number has grown rapidly, a team of 24 now producing 40 bespoke vehicles a year, with long-term plans to ultimately produce 150. Originally based in Cheshire, the Briggs brothers were enticed back to their roots by Liverpool Mayor Joe Anderson following his election in 2012. The company now operates out of an 11,500ft2 facility in the Speke area south of the city, with the nearby John Lennon Airport serving as a convenient test track.

The location also puts BAC in close proximity to large automotive manufacturers such as JLR (Halewood), Vauxhall (Ellesmere Port) and Bentley (Crewe), and the supply chain that has grown up around them. About 40 per cent of the car’s components are sourced from the Liverpool region. Having that resource on the doorstep has been mutually beneficial for company and community, according to Briggs, with BAC’s ‘repatriation’ to Merseyside helping the expansion of the local engineering base.

“If you use Innovate UK’s multiplier, it’s around 40 jobs we’ve created in the supply chain, so 60 jobs [in total] in just under two years is quite an impact. Our supply chain is a ‘best of British’ approach. We’re very proud of that. So the vast majority of the parts that we use are sourced from the UK. They’re a mixture of motorsport suppliers and regular OEM suppliers, and we’ve got a really good balance there.”

When it comes to manufacturing, the localised supply chain helps provide a degree of flexibility that other automotive companies simply can’t match. The Mono also has over 450 parts machined from solid billet, and because BAC doesn’t invest in the costly stamping tools that larger OEMs use for mass production, it can modify and refine individual parts at will.

“This is how we turn a so-called disadvantage as an SME to an advantage,” said Briggs. “A stamped part is not particularly nice, but it does its job. In our case, we machine it from a solid piece of 6082-T6 aircraft-grade aluminium – the best you can get.”

What this means is that each part can be optimised for the function it needs to perform, and there is flexibility for the car to constantly evolve. To test out possible improvements, BAC uses a suite of tools from Autodesk, many of which were used in the original design of the Mono. The advanced CAD systems coupled with machine-tooled parts provide BAC with an impressive level of agility.

“We can make a change in about a week,” said Briggs. “So we can do the analysis, we can then send a DXF [CAD] file straight out to our supplier, and then he can change the programme on his machine.”

Change is something the BAC team is well accustomed to, owing to the level of personalisation it offers and the exacting standards of its clients. Each car is fitted with a unique seat moulded to the customer’s body, manufactured by the same company that provides the seats for Formula One. On top of this, the steering wheel can be customised, built to fit the grip of each individual client.

While each car is ultimately unique, BAC has also introduced some underlying improvements to its 2016 Mono, including carbon ceramic brakes that save 2.5kg per wheel, and a more powerful Cosworth engine. These changes could prove pivotal when a certain BBC motoring show returns later this year.

“You can imagine that when we get invited back that we will be beating that lap time by quite a considerable margin,” said Briggs, “not least because the business has moved on since then, but also because we’ve introduced our 2016 model year car, which is a 2.5 litre engine versus a 2.3, giving us an extra 10 per cent power and torque.”

That Pagani Huayra had better check its mirrors.

Project to investigate hybrid approach to titanium manufacturing

What is this a hybrid of? Superplastic forming tends to be performed slowly as otherwise the behaviour is the hot creep that typifies hot...