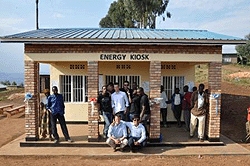

Since forming the project, dubbed e.quinox, in 2008, students at Imperial College London (ICL) have established a charging station in a village of 50 households in the Minazi Sector of Northern Rwanda.

The local population can charge their battery box at the ‘energy kiosk’ for a small fee. The box contains a gel-based lead-acid battery, protection circuitry and two 12V outputs with an LED lamp. The latest version also contains an in-built 65W inverter for providing 230V of AC power for small electrical appliances such as radios and mobile phone chargers.

‘We also found that people are quite creative,’ said Christopher Hopper, the chairman of the e.quinox project. ‘A man found he could put a razor on the battery box − he wanted to open his own barber shop and now we also cater for that.’

The central solar-energy station also makes it possible for powering larger community appliances such as water purifiers.

According to the Rwandan State Minister for Energy, only six per cent of the 9.7 million inhabitants of the country are connected to the grid, but the government aims to increase that figure to 16 per cent by 2012.

The e.quinox team found that lighting is typically provided by kerosene lights and candles in rural communities. Unfortunately, these goods have a long supply chain and have considerably increased in price by the time they reach the end user. Also, burning these substances indoors produce toxic smoke that is inhaled by the inhabitants.

In its Vision 2020, the Rwandan Ministry of Financial and Economic Planning set out a plan to transform Rwanda’s economy into a middle-income country with a per-capita income of about $900 (£580) a year, from $290 today. Among other things, this will require the country to increase electricity access by up to 35 per cent by 2020.

Hopper said that the e.quinox model is the only scaleable solution for electrification in developing countries. ‘Often when people go and think about electrification they think about it in a very Western way,’ he said. ‘You need to go down and put a grid in place − that might be a national grid or micro grid for small communities. While you can do that technically, it’s normally not viable in terms of maintenance and cost, and you’d never get your money back.

‘So what we’re trying to do is not only provide a technical solution but show that it is economically viable, and we hope to prove and demonstrate that a kiosk setup can achieve a payback within five years.’

Red Bull makes hydrogen fuel cell play with AVL

Many a true word spoken in jest. "<i><b>Surely EVs are the best solution for motor sports</b></i>?" Naturally, two electric motors demonstrably...