Michigan University’s Prof Khalil Najafi, chair of electrical and computer engineering, and doctoral student Erkan Aktakka are finding ways to harvest energy from insects so that they can provide power for the cameras, microphones, sensors and communications equipment carried by situation-monitoring arthropods.

Aktakka told The Engineer that the Michigan energy-scavenging work is part of a collaborative research project that aims to build energy-autonomous neural control systems on insects and to demonstrate the feasibility of using them as remote-controlled micro air vehicles.

‘One of the project goals is to develop technology for effective control over insect locomotion, just as reins are needed for control over horse locomotion,’ said Aktakka. ‘Our collaborators in other universities have showed that this is possible. However, the focus of our research group’s work is to build energy-harvesting systems on insects.’

Aktakka added that the Michigan team aims to leverage the efficiency of biochemical energy storage (fat) and bio-actuators (muscles) compared with traditional chemical energy storage (battery), which is limited in its lifetime and results in a heavy payload on the insect.

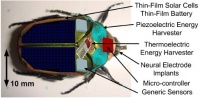

The principal idea is to harvest the insect’s biological energy from either its body heat or its movements. The device converts the kinetic energy from the wing movements of the insect into electricity, which would prolong the battery life. The battery can be used to power small sensors implanted on the insect (such as a small camera, a microphone or a gas sensor) in order to gather information from hazardous environments.

A spiral piezoelectric generator was designed to maximise the power output by employing a compliant structure in a limited area. The technology developed to fabricate this prototype includes a process to machine high-aspect-ratio devices from bulk piezoelectric substrates with minimum damage to the material using a femtosecond laser.

In a paper called ‘Energy scavenging from insect flight’ (recently published in the Journal of Micromechanics and Microengineering), the team describes several techniques to scavenge energy from wing motion and presents data on measured power from beetles.

The university is pursuing patent protection for the intellectual property and is looking for partners to help bring the technology to market.

Red Bull makes hydrogen fuel cell play with AVL

Formula 1 is an anachronistic anomaly where its only cutting edge is in engine development. The rules prohibit any real innovation and there would be...