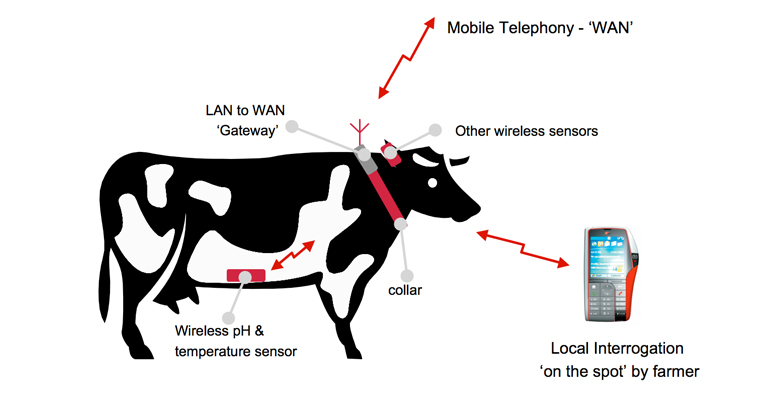

Jointly developed by animal health monitoring specialist Well Cow Ltd and communications expert Ziconix - the technology consists of a so-called “bolus” sensor that monitors the PH and temperature levels within a cow’s rumen, the first compartment of its stomach.

According to Ziconix technical director Steve Sims, by implanting the device in selected cows farmers can gain a valuable overall picture of the herd’s health. This can help them identify digestive problems at an early stage and act quickly to resolve them before they impact the efficiency of milk production.

The technology could also help farmers make dietary adjustments that could reduce the herd’s production of methane, which is a potent greenhouse gas.

Jim Watson, director of Innovation and Enterprise Services at Scottish Enterprise, which provided £96,000 funding for the trial, said that more accurate data collection could yield an estimated £18 billion of productivity benefits.

During the latest trials, which were carried out at Edinburgh University’s Langhill Farm, three randomly selected animals were instrumented with the sensor and observed over a period of a couple of days. In a typical application, around a fifth of the herd would be instrumented with the sensors.

Sims told The Engineer that the chief advantage of the technology over existing swallowable sensors is its range: it is able to transmit data wirelessly over a distance of up to 30 metres. This makes the system much more commercially appealing to farmers as it means that herds can be scanned quickly and autonomously.

Commenting on the technical challenges of developing the device, Sims said: “The rumen of a cow is not a nice place for any electronics to survive and establishing reliable radio transmissions to and from the cow, through its body mass and achieving the distance required is very difficult and required us to use the most sensitive radio transceivers available and fine tuning of the antenna system to accomplish this.”

Due to concerns over toxic materials entering the food chain, the device is powered by an alkaline battery rather than a more powerful lithium source. This meant that another key challenge was reducing the power requirements of radio technology. According to Sims the current device has a battery life of a couple of days, and efforts are now focused on further reducing the power requirements ahead of commercialisation.

Well Cow’s Malcolm Bateman described the technology as a step change for farmers and added that the underpinning technology could be applied to various other areas of animal health monitoring.

Red Bull makes hydrogen fuel cell play with AVL

Formula 1 is an anachronistic anomaly where its only cutting edge is in engine development. The rules prohibit any real innovation and there would be...