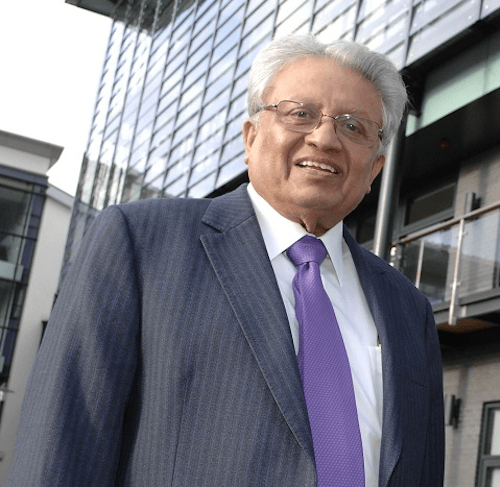

Lord Kumar Bhattacharyya

Chairman, Warwick Manufacturing Group

Prof Lord Bhattacharyya was born in Dhaka and after graduating from the Indian Institute of Technology, Kharagpur, one of India’s premier technological research institutes, he was invited to become a graduate apprentice at Lucas Industries in the UK. After completing his graduate apprenticeship, he was offered the Lucas Fellowship and entered the University of Birmingham where he attained an MSc in Engineering Production and Management and a PhD in Engineering Production. Before completing his PhD at Birmingham, he was appointed as a lecturer and began the process of establishing a manufacturing education programme for industry there. The UK's first ever professor of manufacturing, Lord Bhattacharyya is an advisor to many companies and organisations around the world, and has advised the UK government on manufacturing, innovation and technology, including former prime ministers Margaret Thatcher and Tony Blair.

A minute into the interview with Lord Kumar Bhattacharyya, it is evident that he believes Britain’s decision to leave the European Union is not the Armageddon for engineering and industry that many people feared.

The chair and founder of Warwick Manufacturing Group (WMG) speaks with the near blasé assuredness of someone who has witnessed huge change in Britain and who is focused on goals that are even more long term than our membership of a supranational bloc. “The world is much bigger today. How do we explore other markets? India is one of the biggest investors in the world. There is a lot of love for the UK in India,” said the eminent engineer and pro-Remainer. “You have to get on with it. I am a pragmatist,” he added, pointing out that EU competition laws have complicated and delayed decisions by some multinationals to invest in Britain.

He should know about Indian opportunities. From ordinary beginnings as a graduate apprentice at Lucas Industries in the 1960s through to founding WMG in 1980 and receiving a knighthood for services to engineering and industry in 2003, Lord Bhattacharyya has worked closely with Indian companies to create Anglo-Indian ventures, most notably brokering the takeover of Jaguar and Land Rover by Indian industrial giant Tata Motors in 2008.

His vision for the UK has always been ambitious, rooted in long termism and the crucial role of investment. “I brought steel here,” he said without hyperbola, referencing Tata. “The reason why it is in trouble is lack of investment,” in reference to the precarious future of UK steelmaking since Tata Steel announced in May it would sell the loss-making Port Talbot steelworks. A friend of former Tata chairman Ratan Tata, Bhattacharyya said that he is developing the strategy for Tata Steel to remain here.

But won’t multinationals now question their commitment to existing and future investment in the UK since Brexit? Consider Siemens UK’s managing director Juergen Maier’s comments in late June about “reviewing Siemens’ future investment” in facilities such as the offshore wind turbine factory in Hull. And might many companies linked to WMG’s expensive research facilities, such as the National Automotive Innovation Centre, get cold feet at this uncertain time? “I don’t think so at all,” said Bhattacharyya. “They come here mainly for technological purposes. They are not coming here for short-term financial benefit, mainly for science and technology, and once they develop this they benefit. They are not particularly worried about where Britain lies, as long as they can be a part of [the success]. And geographically we are still a close market.”

He added: “I am sure that when the deals are done, it won’t be as black and white as people think, because all countries have got bilateral relationships and agreements with industrial companies, and agreements on [their] science base.”

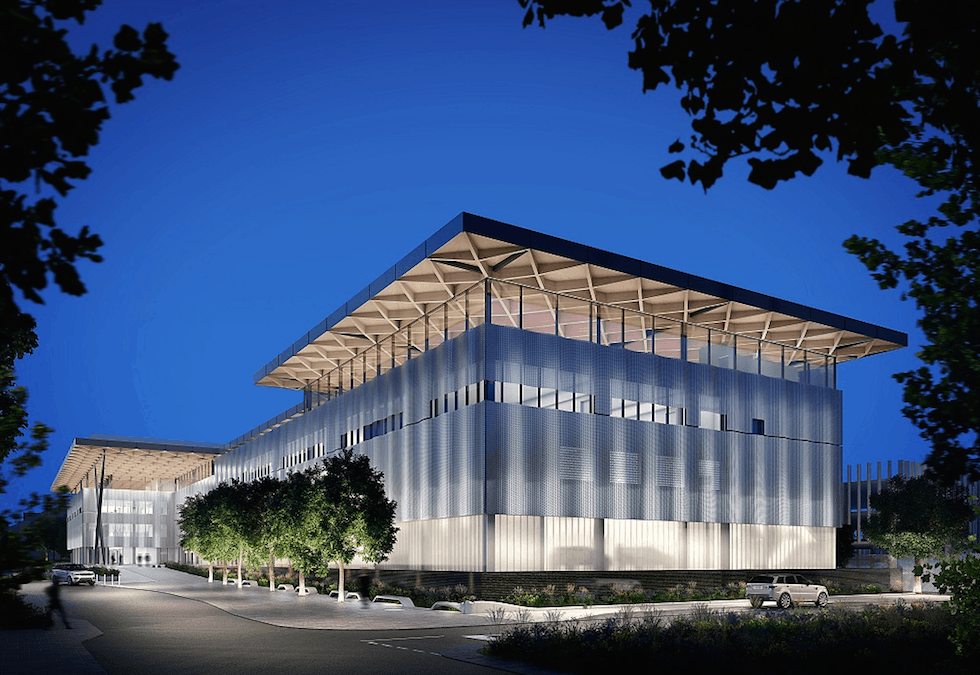

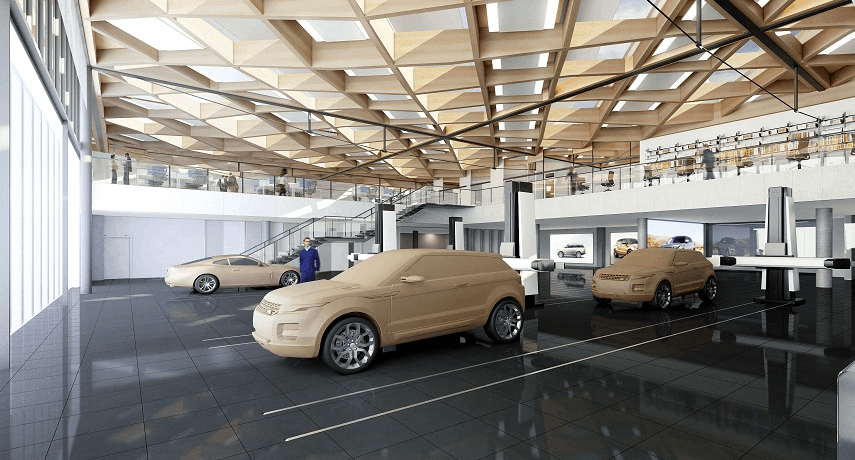

This grounded view of business fundamentals is reflected in the Warwick Manufacturing Group. With turnover of £150m and nearly 500 employees, it is home to a big range of engineering research, but one sector dominates: automotive. WMG’s biggest investment to date, in build now, is the National Automotive Innovation System (NAIC). The numbers are big: £150m for the building, rising to £300m when accounting for investment in capex and people. He mentions £1bn – perhaps the total economic impact of the combined auto centres. “It is the single biggest privately funded investment by any university in the UK,” said Bhattacharyya. The 33,000m2 centre will research new automotive technologies and build prototype cars. NAIC is about taking design and research through to manufacturing.

The central theme for NAIC is low carbon and electric propulsion, about which Bhattacharyya is evangelical. “The design of new cars is the future. They have to be very, very lightweight. The car has changed very little over the years. Another big change now is vehicle autonomy – to assist the driver – low carbon and batteries.”

As well as major investors, including Jaguar Land Rover (JLR), which has put £50m into the building, NAIC works with several automotive tier-one suppliers, including Bosch, Continental and ZF, and it is attracting more. “We work with Nissan, battery companies; we have been approached by German companies because suddenly they are excited about what we are doing. What we are doing is being monitored by the competitors of JLR. If they can come in and benefit from it, they will.”

How does that sit with JLR? “There are two levels, one is commercial competitiveness – that will remain with JLR. The fundamental science, that can be transferred without any problem,” he said. “And sometimes JLR will also ask if it can work with XYZ, so that both companies can benefit, even a rival OEM. And with these new technologies, not everyone will build a battery factory.”

To complement the flagship NAIC, WMG built the Energy Innovation Centre, which includes a £13m battery materials scale-up Pilot Line that develops new battery chemistries from concept to proven traction batteries, and a battery characterisation laboratory. Then there is the Advanced Propulsion Centre, a 10-year, £1bn industry- and government-funded project for developing low-carbon propulsion systems. In July 2014, the University of Warwick was chosen as the site for its hub location. “To design and manufacture low-carbon engines, do we look at a combination of propulsion types or just a single propulsion? How do you make that efficient?,” said Bhattacharyya. “Irrespective of whether it’s electric or not, you want lightweighting. So the APC works as part of a lightweighting research centre but in a different way to working with internal combustion engines or with electric motors. How do you design electric motors that are part of the total system, rather than in isolation? There is no point in us having an energy [storage] centre if we don’t have a propulsion centre. It is so coupled. Materials, electric motors, batteries and new means of energy transfer in the powertrain.”

Bhattacharyya is a government advisor on engineering and manufacturing. What does he make of the new-look Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) given the trail of underwhelming manufacturing strategies of the past decade? “The new prime minister bought in the Industrial Strategy at the heart of policies on day one [of the new administration]. We have to be sure that production is as good as the world’s best. Concepts such as the Northern Powerhouse and the Midlands Engine, they are piecemeal. I am confident that the government will deliver on a national industry strategy.”

Bhattacharyya has campaigned indirectly or directly for the UK to invest in engineering skills since his PhD at the University of Birmingham in the 1960s. Since the main drive for creating a ‘technical class’ began at the end of New Labour in 2009, has Britain got closer to filling the skills gap? “No, it is just as bad,” he said. “It’s easy for politicians to talk, somebody writes a speech and they talk. To implement it is a huge task. You have to have the infrastructure to implement it. That is why I am so keen on the Industrial Strategy.” Meanwhile WMG is, unsurprisingly, doing its bit on skills. It now has both a University Technical College, the WMG Academy for Young Engineers, and an apprentice school, which has nearly 400 starts and aims to have 1,000 by 2020. “We are spending £20m on a brand-new building and we are helping SMEs with the Apprenticeship Levy, in effect paying part of the levy for them and we develop the curriculum and how it should be taught.”

Red Bull makes hydrogen fuel cell play with AVL

Formula 1 is an anachronistic anomaly where its only cutting edge is in engine development. The rules prohibit any real innovation and there would be...