Mark Miodownik talks about man-made materials, objects and structures with the same wide-eyed, boyish wonder that physicist and TV presenter Brian Cox waxes about cosmic phenomenon.

But any hopes that Miodownik might be the poster boy for engineering that some have been calling for are, I fear, misplaced. It’s certainly not through a lack of charm or charisma, which he has in spades, but rather a maverick, renegade quality that may not sit well with everyone in the community.

’If you go and visit engineering companies and labs, you find that they’re kind of islands with a very particular way of approaching the world,’ said Miodownik.

It’s an approach he knows well after completing the most macho of engineering PhDs in ’turbine jet engine alloys’ at Oxford University. He holds considerable sway as an academic in the traditional sense, publishing through the normal avenues with research on self-healing materials. But he has always been keen on the cultural and aesthetic aspects of engineering - resulting in collaborations with Tate Modern and the Hayward Gallery.

’When I started teaching, I got people saying “that’s just the wishy-washy stuff” and it’s then you realise you’re up against more than just antagonism, but protection of an idea of engineering that’s only quantitative and in no way has any other dimension.’

Perhaps his biggest coup was the creation of the Materials Library, which originally started off in the same vein as many a boyhood collection - the hoarding of a few interesting objects to engage others’ fascinations (see panel).

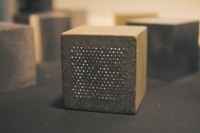

’I realised that the key to getting people interested in materials science and engineering was these physical objects that were outputs of labs around the world but were often incomplete materials, ones that were never going to make it into the world - but that made them more interesting.’

At first, it was just a conversation starter, but in time it caught the attention of architects and designers who began to use it as a source of inspiration. With a £70,000 grant from the National Endowment for Science, Technology and the Arts (NESTA), he was able to expand the library and make it available to the public.

The library’s scope includes Aerogel, the world’s lightest solid and best insulator, and its thermal opposite, a slice of aluminium nitride that can cut through ice by conducting heat from the body of the person holding it.

Such was the success of the Materials Library that Miodownik decided to expand the concept further with the help of long-term partners and fellow ’material addicts’ Zoe Laughlin and Martin Conreen (both artists). The resulting Institute of Making will sit within the umbrella of King’s College London but will have its own premises in the east wing of Somerset House, just off the Strand, when it opens in January 2012.

As well as becoming a new home for the Materials Library, the institute will be a fully fledged research vehicle - but focused on questions such as why things taste a certain way from a molecular point of view. Public outreach will also be key, with a Festival of Making planned annually for the autumn.

Although Miodownik acknowledges that the institute is likely to remain unique and something of an oddity, he maintains that engineering departments, companies and even governments themselves may benefit from a similar, more holistic approach.

’It seems to me ludicrous that engineering and science are separated from the arts and humanities in such a drastic way, when they used to be so close together,’ Miodownik said. ’They’re built of the same sort of people who are curious about the world - who want to comprehend and change the world - and yet the reality is the barrier between individual departments is huge.’ Not only does that inhibit the free thinking of those already in the profession but restricts access to those outside, he added.

’That [approach] has cut engineering off from the rest of the world, and if we don’t do something about it it’ll be as isolated in 10 years’ time as it is now and we’ll have as few women and other talented people not going into it because they want a more nuanced view of how it connects,’ said Miodownik.

As a materials scientist, he also laments the conservative nature of the construction sector and the regulatory regime in which it operates, which he believes is stopping the adoption of energy-efficient technologies.

Miodownik admitted that materials that come out of labs are invariably costly but said they are not being given a chance to prove themselves, so economies of scale can never take effect. One of his solutions is characteristically far out. He points towards the proposal in the US to build a medium-sized, uninhabited city in New Mexico to test out new telecommunications equipment.

’In the UK, we need to do something similar that has reduced planning restrictions and reduced corporation tax so people can put up buildings and telecommunications infrastructure that is experimental… and they can play around with it. At the moment, there’s this barrier to innovation because of all the regulations.’

Mark Miodownik

Biography, Research director, Institute of Making, King’s College

Education

1992 BA in Materials Science (1st Class) from St Catherine’s College, Oxford

1996 PhD in turbine jet engine alloys from Oxford University

Career

2000 Joint appointment at the Division of Engineering and the Department of Physics at King’s College London

2003 Awarded a NESTA fellowship to create a Materials Library as an interaction space for designers, architects and artists to collaborate with materials scientists

2005 Appointed head of the Materials Research group at King’s College London

2010 Selected to give the Royal Institution Christmas Lectures

2011 Started work setting up the Institute of Making with Zoe Laughlin and Martin Conreen

Q&A Living in a material world

How did the Materials Library come about?

It’s one of those projects that was a hobby. I used to have all these materials in my drawer and when undergraduates would come in and say “I’m thinking of doing a PhD” or “what’s materials science like?” I’d fish something weird out and show it to them and I always noticed that it’s a much better starting point for any conversation about research. It’s weird how [materials] have this magic talismanic quality about them. As soon as you have something in your hand and there’s something special about it, you’re much more engaged; it’s like there’s another person in the room and you’re talking about them.

How does a material get into the library? What are the criteria?

You have to have a story. That’s the thing about materials. They often embody a human story: a struggle against the elements, a struggle against communicating. And the materials that really shine are the ones where the story is unique. Stainless steel is a really good one; steel has been used for thousands of years as a hard, strong, tough material and its only problem is that it rusts, but you couldn’t possibly make it not rust; that’s just impossible. It wasn’t seriously thought of as a proposition. Then suddenly, one day accidentally in Sheffield, they discovered it.

Why evolve the Materials Library into an Institute of Making?

There are loads of material science departments around the world that are dedicated to solving engineering problems for engineering applications - new jet engines, new cars, new hoovers - but how many labs or institutes are dedicated to solving aesthetic problems that are intriguing and interesting? We found there were none, so we had to start.

With advances in materials, 3D printing, biomimetics and metamaterials etc, will we soon be able to simply design materials for certain tasks?

I think it’s heading that way. With 3D printing at the moment, you can do lots of shapes with single materials, single microstructures. But in the future you might be able to porosity grade 3D printed materials and that can open up a whole world, where the object and the material are essentially not different things. Like in biology, there isn’t tissue then the organism; there’s the organism and different levels of tissue. We’re a long way off it, but that’s probably where we’re heading.

Swiss geoengineering start-up targets methane removal

No mention whatsoever about the effect of increased methane levels/iron chloride in the ocean on the pH and chemical properties of the ocean - are we...