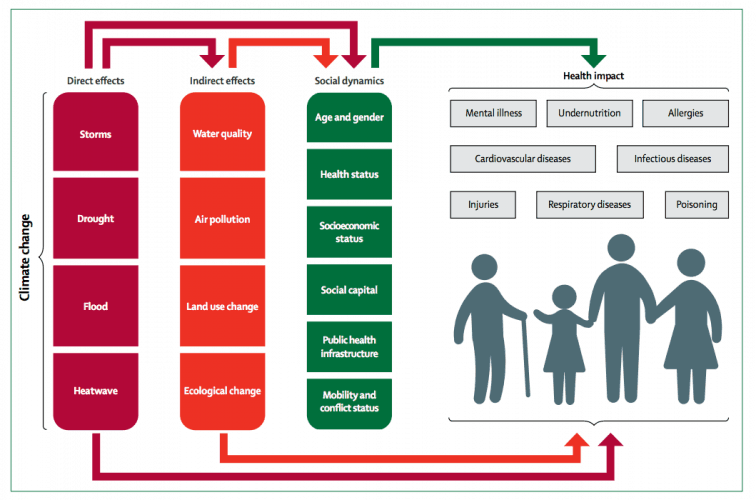

The second Lancet Commission on Health and Climate Change outlines the danger to humanity from increased heat waves, floods, droughts and storms, as well as indirect health impacts such as air pollution, food shortages, and disease. The Commission says that the technology and finance to mitigate against global warming and its effects are available, but that the political will to implement them is lacking.

“Climate change is a medical emergency,” says Professor Hugh Montgomery, director of the University College London (UCL) Institute for Human Health and Performance, and co-chair of the Commission.

“It thus demands an emergency response, using the technologies available right now. Under such circumstances, no doctor would consider a series of annual case discussions and aspirations adequate, yet this is exactly how the global response to climate change is proceeding.”

According to the report, if emissions remain constant, we will reach a tipping point between the next 13 and 24 years that is likely to raise global temperatures by more than 2 °C - the threshold set by experts for avoiding the worst effects of climate change.

The report also claims that to stabilise CO2 concentrations, global emissions will need to fall by between 3-6 per cent per year, “a rate that so far has only been associated with major social upheaval and economic crisis.”

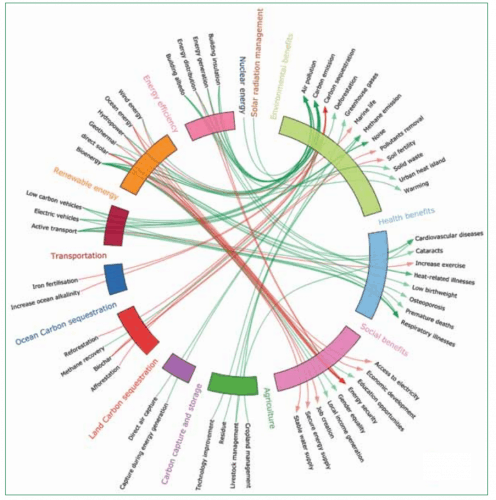

In order to address the climate crisis - and its associated health implications - the Commission calls for immediate global action, including “the reduction of costs of mitigation options, carbon pricing, improvement in the research and development process and the implementation of policies and regulations to act as enabling mechanisms, as well as recognition of the strong near-term and long-term co-benefits to health.”

According to the report, the near-term health benefits could be significant. Air pollution from the UK power sector is estimated to cause 3,800 respiratory-related deaths each year. Globally, that figure rises to 7 million, with the emerging economies of Asia particularly badly affected. Air pollution in China is estimated to reduce life expectancy by about 40 months, but this could be cut in half by 2050 if climate mitigation strategies are put in place, claims the Commission.

Implementing those strategies requires major investment, but the financing is available, says Paul Ekins, director of the UCL Institute for Sustainable Resources and a contributor to the report. On top of the $105 trillion estimated to be required between 2010 and 2050, Professor Ekins believes an additional $1 trillion a year is required to transition to a low carbon economy. To put these figures into some context, the global spend on health each year is approximately $68 trillion, while private institutional investors have around $76 trillion under their management.

A global carbon tax programme would encourage the transition, says Ekins, but its financial impact could be balanced out through a cut in VAT or reduced labour taxes. In this way, climate-friendly consumption could be encouraged, while carbon-intensive activity – such as air travel – would most likely increase in cost.

Changes to how we live are inevitable, says the Commission, and lifestyles that contribute most to the problem are likely to be impacted most. This, in turn, will have wide-ranging effects on health, according to Montgomery. “It just so happens that a lot of high-carbon lifestyles are desperately unhealthy,” he says.

According to Professor Anthony Costello, co-chair of the Commission, and director of the UCL Institute for Global Health, although the implications of climate change are worrying, tackling the issue could actually be the biggest health opportunity of the 21st century.

“Our analysis clearly shows that by tackling climate change, we can also benefit health,” he says.

“Tackling climate change in fact represents one of the greatest opportunities to benefit human health for generations to come.”

April 1886: the Brunkebergs tunnel

First ever example of a ground source heat pump?