Education

1983: Completed studies in business and administration in Mannheim, Germany; continued as an assistant professor for four years

Career

1987: Joined Bosch as a trainee; worked as a manager in purchasing, logistics, personnel, controlling and corporate planning

1998: President and chief executive officer of Bosch Sanayi ve Ticaret in Turkey

2000: Vice-president of the German Turkish Chamber of Industry and Commerce

2004: Executive vice-president for finance and administration at Robert Bosch Automotive Aftermarket Division

2009: President of Bosch UK

One of the more curious facts about the engineering sector is that the public profile of many companies is very much at odds with what they really do. Sometimes it’s completely wrong — for example, Rolls-Royce probably still conjures up images of posh cars to the public, rather than jet engines. Sometimes, though, it’s just that the public image is the tip of a huge, hidden iceberg. German company Bosch is best known in the UK for power tools and household appliances but, as its UK president Peter Fouquet is keen to explain, it’s actually a vastly diverse operation, reaching out into most of the technology sectors, with a turnover in the UK of some €2.2bn (£1.7bn) annually.

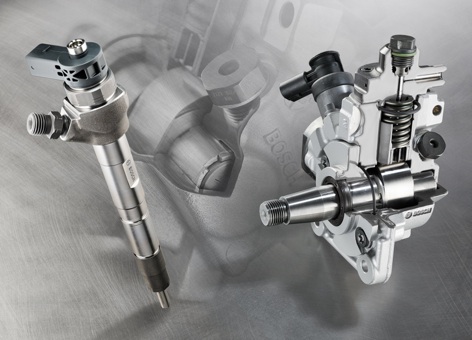

‘Household goods is actually only 10–15 per cent of our business in the UK,’ he said. The company’s biggest division, accounting for almost half of its income, is automotive, for which it is certainly well known in industry, providing engineering services for almost every system in cars and commercial vehicles, from vital components for the engine, such as fuel-injection systems, to chassis and comfort features. ‘We serve all the automotive businesses in the UK, from the big-volume producers such as Nissan, Toyota, Jaguar Land Rover, Ford, GM [General Motors] and BMW MINI and also the smaller ones such as Bentley and McLaren,’ Fouquet said. ‘We’re involved in the whole lifecycle of the vehicle, from development through to recycling.’

The company is also a vital part of many households through its Worcester-Bosch division, the market leader in wall-hanging gas boilers; it also makes lawnmowers and garden power tools through a subsidiary in Stowmarket, Suffolk, where it is currently developing a robotic lawnmower. A factory in Glenrothes, near Edinburgh, makes hydraulic engines for small off-road vehicles, such as the Bobcats used to carry materials around large building sites, while another subsidiary, Liverpool-based Manesty, makes tablet presses, coating machines and packaging equipment for the pharmaceutical industry.

‘We’re also involved in security systems — all the closed-circuit TV cameras in the Palace of Westminster are Bosch, and they’re equipped with face and number-plate recognition systems that we produce,’ Fouquet said. ‘And if you get flashed on the motorway by a speed camera, that’s Bosch too.’

A growth area for the company is telehealth, providing equipment and training for patients to monitor their condition at home and for nurses and doctors to manage the data this generates, and to respond to changes in their patients’ conditions. Bosch is the market leader in this sector in the US, with some 50,000 patients, Fouquet said, and currently has five projects under way within the NHS, two almost ready to ramp up and three at an early stage. ‘It’s true that this field is really in its infancy in the UK, but it’s by far the most advanced market in Europe; the government here has been thinking about this for some time,’ he said. ‘We have several other projects at a discussion phase, where we are talking about contractual arrangements with the customers, which are hospitals, private-care providers and the NHS itself.’

The UK was Bosch’s first non-German outpost, with the company starting operations here in 1889, and it remains an important market. ‘We have virtually every division represented here, with 38 locations and more than 4,000 employees, and we have production, research and development,’ Fouquet said.

“Sterling is getting stronger, which will hurt the export business. We have to make sure the UK remains competitive

But like all businesses at the moment, the company is experiencing tough times. ‘I see the market here as more stable than southern Europe, but what concerns me is the currency,’ he said. ‘Sterling is getting stronger, which will hurt the export business, and so much industry in the UK depends on exports, especially in the most developed sectors: aerospace, automotive and defence. We have to make sure that the UK remains competitive.’

In some respects, the UK is a good place to do business; Fouquet believes it is no longer a high-cost country compared with the rest of western Europe and even some parts of eastern Europe, in part because it is easier to find people with good qualifications.

For Bosch’s consumer-facing operations, tightening household budgets are a problem. ‘Inflation’s quite high and we’ve had several years where wage increases were below inflation,’ Fouquet said. ‘A new gas boiler costs about £2,000, which is a large amount for a household to find. We know there are five million very old boilers in the UK that will need to be replaced. So, we wait.’

Automotive businesses are being squeezed by conditions on the continent — demand is down from Bosch’s customers in southern Europe and France. ‘But the UK is a different market, because it’s the second-largest producer of luxury cars, and they are performing well in many markets,’ he added. ‘In the short run, I don’t see any problem with those producers.’

“Will we be able to sell big SUVs in five to ten years’ time?

Longer term, however, the situation becomes more murky. ‘Will we be able to sell big SUVs [sport utility vehicles] in five to 10 years’ time? We need a lot of new models, which can show that these cars are capable of being economical,’ Fouquet said.

This is an area where Bosch might have solutions, he explained. The company is deeply involved in research to boost the power output of smaller engines, both diesel and petrol powered. ‘Big SUVs will be driven by smaller engines,’ Fouquet said. ‘Now, they are mostly three-litre-plus, but in a few years we will downsize that to a two-litre engine, double turbo with high-pressure injection, of the same power as the three-litre.’

Fouquet believes that the fuel efficiency of both diesel and petrol engines can be increased by 30 per cent, and this, he said, is part of the reason that Bosch still considers electric and hybrid vehicles to be a niche in the automotive sector. ‘We can’t go to 90 per cent electrified cars in the near future; you won’t be able to distribute the energy,’ he said. ‘And the cost is higher for a hybrid because you need to add an electric engine, battery, converter and expensive steering electronics. Moreover, compared with a high-efficiency diesel engine, hybrids don’t give you any real advantage in terms of fuel use. We expect in 2020 some 125 million cars to be produced worldwide, and six to seven per cent of those will be electric or hybrid.’

Status and recognition

You’ve written for The Engineer about recruitment issues. Do you think enough is being done now to attract young people into science and technology?

A lot of things have happened in the last two to five years to make engineering more attractive. I think people are coming to know that the person who comes to install the boiler or service your security system is a technician, not an engineer, and that engineering is at a much higher level. We’re seeing that also in the discussions with young people and with universities — they are keen to bring in more capacity for engineering students.

What’s Bosch’s view on the state of engineering education and training in the UK?

We have very good universities that provide engineering graduates, but still, I think, they’re not at the level that means that we don’t have to provide training ourselves when they come to us. We have to give them the right understanding of the technology, and we are really not happy about that. There has to be more of a focus on technology and basic skills, more budget for that, and it means that you have to train the professors as well as the students.

How does this compare with the situation in Germany?

I don’t want to compare the two education systems too much, but we benefit a lot in Germany from our apprentice scheme — this has been discussed in the UK for ages now, and nothing really happens. Our scheme in Germany is very fixed. You have more or less the same rules nationwide: up to three years of apprenticeship combined with education at a specialist vocational school, and the exams are also to the same standard everywhere. Many of them afterwards go to university with the best knowledge you can imagine.

How could the situation be improved in the UK?

The government would have to provide the framework and also the schools. I’m sure that companies would be keen to support that with apprenticeships and also with supporting the schools.

Red Bull makes hydrogen fuel cell play with AVL

Many a true word spoken in jest. "<i><b>Surely EVs are the best solution for motor sports</b></i>?" Naturally, two electric motors demonstrably...