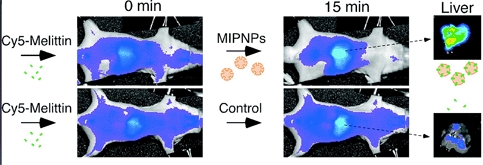

The polymer nanoparticles, designed to mimic the proteins produced by the body’s immune system, were used to combat bee venom injected into mice.

The team behind the discovery, reported in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, now hopes to use the plastic antibodies to fight other medical threats such as disease-causing bacteria and viruses and particles that cause allergic reactions.

The nanoparticles are created around a template so that they match the shape of the target molecules and can capture and neutralise them.

Using a process called molecular imprinting, typically used to separate and concentrate chemical solutions, the team at the University of California, Irvine, created particles that matched molecules of melittin, the toxin in bee venom.

The scientists used a catalyst to form solid polymers around molecules of melittin and leached the poison out to leave nanoparticles with holes that matched the shape of the toxin.

The technique has been used to create plastic antibodies before, but this is the first time they have successfully been used in a live animal.

‘In order to function in a biological environment such as the bloodstream, the recognition and binding by the synthetic nanoparticle must take place in the presence in a sea of competing molecules - for example proteins, peptides or cells,’ lead researcher Kenneth Shea told The Engineer.

‘The polymer nanoparticle must avoid being cleared by the natural filtering systems of the blood and must not trigger an immune responses. All of these present formidable challenges for the design of a nanoparticle.’

Although the development of the technique for use in humans is thought to be at least five to ten years away, the plastic antibodies could easily be manufactured on a large scale and the starting materials are relatively inexpensive.

‘Manufacturing costs will be much lower than the usual antibodies once we optimize the procedure,’ said Shea’s colleague, Yu Hoshino.

‘We have just shown plastic antibodies for the first peptide target. We have to develop a method to prepare plastic antibodies for more complicated target such as proteins.’

Click here to access the report from Journal of the American Chemical Society.

Red Bull makes hydrogen fuel cell play with AVL

Surely EVs are the best solution for motor sports and for weight / performance dispense with the battery altogether by introducing paired conductors...