Now a prototype smart shirt, equipped with sensors that monitor movement, is being developed by a team at Germany’s Fraunhofer Institute for Silicate Research ISC in Würzburg.

The MONI shirt, which is being presented at IDTechEX on 27 and 28 April and was developed in collaboration with researchers at Fraunhofer ISIT, contains a transparent material printed with a piezoelectric polymer sensor paste.

The ferroelectric polymer paste is flexible, non-toxic, and registers pressure and deformation, allowing the material to act as a touch and motion sensor. It is also pyroelectric, meaning it is sensitive to changes in temperature and as a result can be used as a proximity sensor.

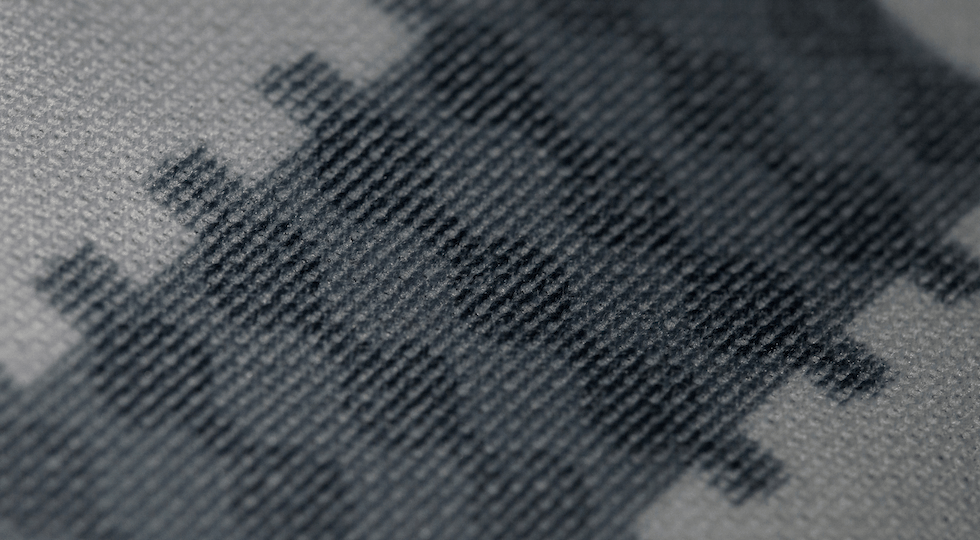

The paste is deposited onto the fabric or surface using a simple screen printing process. The paste is applied to a screen, which is then placed onto the substrate, according to Dr Gerhard Domann, head of the competence unit for optics and electronics at Fraunhofer ISC.

“A squeegee or blade presses the paste through the screen, which is partly covered by photopatterned coating, so that only on the positions where there is no coating on the screen is the paste transferred to the substrate,” said Domann.

In order to ensure the process results in a good print, the paste must have a high viscosity, but act more like a liquid under pressure, said Domann. “Thus, the paste can be transferred easily through the screen, but after printing the material’s viscosity increases, which helps to ensure the paste is not smeared,” he said.

Once printed onto the material, the sensors are subjected to an electric field, which ensures the piezoelectric polymers all align. Any change in their alignment caused by pressure or deformation will then generate an electric charge that can be measured as a voltage.

The printing process is cheap and widely used, and could allow the technology to be mass-produced.

Since the sensor paste is flexible and transparent, it can be used in a wide range of fabrics of different colours. The ultra-thin sensors also do not need an external power source, as they are able to harvest energy from the movement of their wearer.

The technology could ultimately be used to monitor elderly people for signs of difficulty such as a fall, for example. It could also be used in healthcare to monitor hospital patients’ vital signs, such as their temperature and breathing.

The sensors could also be used as part of the Internet-of-things, said Domann. “The sensors have some unique properties such as the freedom of design, and the possibility to produce sensor arrays over a large surface,” he said.

Swiss geoengineering start-up targets methane removal

No mention whatsoever about the effect of increased methane levels/iron chloride in the ocean on the pH and chemical properties of the ocean - are we...