Andrew Wade, senior reporter

Andrew Wade, senior reporter

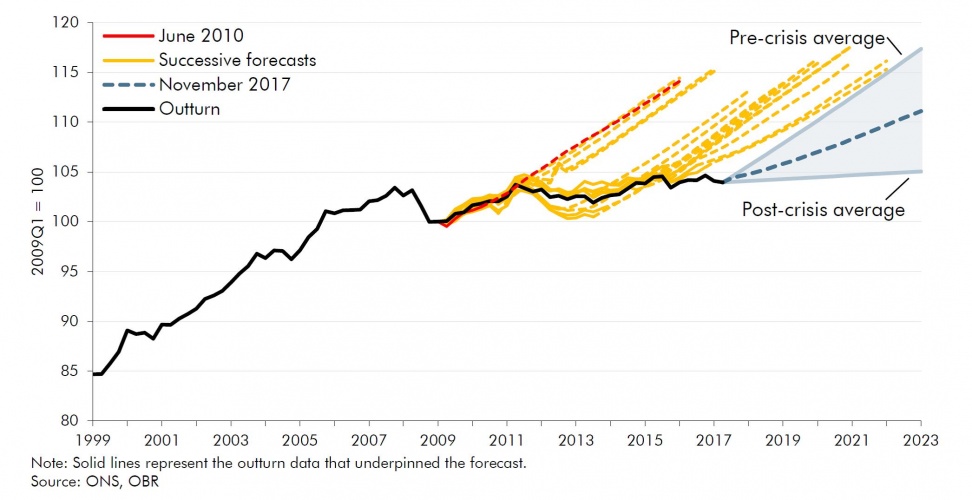

The downgraded productivity figures revealed in this week’s budget statement made for stark reading.

A decade of struggle in the wake of the financial crisis is metastasising into a settled trend, with the long-anticipated return to pre-crash productivity levels looking increasingly like wishful thinking. And while the productivity problem is one that has puzzled many countries since 2007, the UK’s predicament is worse than any other G7 nation. Just yesterday it was revealed that France has overtaken the UK as the world's fifth-biggest economy. By virtually all measures – with unemployment being the one glaring exception – the country is going backwards.

Ultimately, of course, lower productivity means lower living standards. Combined with lower growth, higher inflation, a fall in real-terms wages and consumer debt approaching record levels, you have the makings of a perfect economic storm on the horizon. Using the downgraded numbers for growth and productivity, the Institute of Fiscal Studies predicted yesterday that by 2021, average earnings will still be below their 2008 levels, adjusted for inflation. The gloomy outlook is filtering down to households too, with consumer confidence at its lowest level since the immediate aftermath of the Brexit vote.

In recognition of the approaching dark clouds, Philip Hammond’s budget was a marked departure from recent editions, with £90bn of extra borrowing over the next five years announced. The pillars of austerity remain, but there was undoubtedly an easing of sorts. Extra money was found for the NHS, the delivery of Universal Credit and the preparations for Brexit. But in terms of big-ticket announcements to provide hope in the face of the productivity crisis, we were left surprisingly short.

Half a billion was announced for 5G, fibre broadband and artificial intelligence research. Not to be sniffed at, by any means, but against the backdrop of the DUP receiving double that for propping up the government, it starts to look a little anaemic. Likewise, the £540m allocated to electric cars and charging networks. Given the recently announced plans to phase out petrol and diesel sales from 2040, a lot more will be required to kick the EV revolution into gear, and the infrastructure will not appear overnight.

Earlier in the week an extra £2.3bn R&D spending was announced, but will not materialise until the last year of this parliament. The £7bn boost to the UK’s national productivity investment fund won’t be seen until a year later, in 2022-2023. On the positive side, £1.7bn has been set aside for a city region transport fund, with around half going to areas with elected metro mayors such as Greater Manchester and Tees Valley. And while Hammond is to be commended to some degree for these measures, economists have said they fall well short of the level of investment needed to address the productivity disaster that is emerging.

Infrastructure would seem an obvious place to go on the offensive. Marquee projects like Swansea Bay Tidal Lagoon – which received broad approval in the independent report from former energy minister Charles Hendry – has been held up for what seems like an age. Issues over strike price are understandable, but Swansea will be a pathfinder project and could provide a blueprint for an entirely new energy sector, and expertise that could be exported around the globe. At £1.3bn it looks a bargain, especially in light of some of the other figures we’ve been confronted with this week.

Transport links in the north have long been neglected, and large-scale investment here could boost the region, helping close the vast productivity gap that has opened between parts of the UK. Not to mention the jobs that would be created and the skills that would be developed. Ultimately, we need investment in technology, as well as the people that can make it work. Despite what some publications would have us believe, the elevation of companies such as Just Eat (of which I am a customer and a fan) at the expense of one like Babcock is not something to be cheered, and will do absolutely nothing to solve the deep-seated issues the UK is currently facing. Project Fear is fast becoming Project Reality, and the current government looks dangerously short on answers.

JLR teams with Allye Energy on portable battery storage

This illustrates the lengths required to operate electric vehicles in some circumstances. It is just as well few electric Range Rovers will go off...