But not all steam enthusiasts confine themselves to pictures, models, train sets, or even the loving restoration of old trains to run on heritage lines such as the Bluebell Railway in Sussex. For some, the best steam locomotive is a new one: and one is currently taking shape in Lincolnshire. It’s only the second mainline steam locomotive to be built in the UK since 1960; and the team on this project was in fact also responsible for the first: the Tornado, a revised version of the London and North Eastern Railway’s (LNER’s) A1 design, which went into service in 2008 and now runs on special services up and down the country.

The latest project for the team is another LNER locomotive: the P2, which was originally designed by the LNER’s then-chief engineer, Sir Nigel Gresley, in the early 1930s. The first, Cock o’the North, went into service in 1934. Gresley is best known as the designer of the Flying Scotsman and the Mallard, the steam speed-record-breaking locomotive, and its fellow A4 class engines. Although much less well known, the P2s had an equally special place in steam history: they were the most powerful steam locomotives ever built to operate in Britain.

Only six P2 locomotives were ever built, and none survive — they were all converted into a different class by Gresley’s successor as LNER chief engineer, Edward Thompson. They were built specifically for the Edinburgh to Aberdeen line, an arduous, hilly route that was causing particular problems in the 1930s. LNER had scrapped its second-class service, with the result that passengers who couldn’t afford to upgrade to first demanded better facilities in third class. As a result, the carriages became heavier and heavier until the weight of the train topped 600 tons. This required two locomotives to haul over up to Aberdeen, so Gresley designed the 170-ton P2 to be capable of pulling the heavy carriages on its own.

‘P2s are something of an enigma and very popular with rail enthusiasts,’ explained Mark Allatt, chairman of the P2 Steam Locomotive Company, which has been set up to build the locomotive. ‘They looked like nothing before or since and they were huge, plus they only existed for a relatively short time. There’s a real glamour to them.’

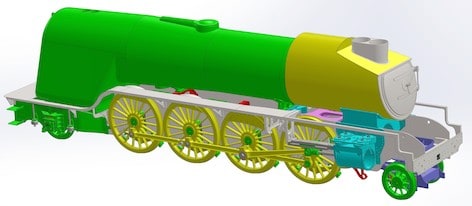

The P2’s unique look resulted from Gresley’s semi-streamlined design, a forerunner to the sleek curves of the A4 class with the chimney stack set back in a v-shaped angled housing, along with the wheel arrangement. This is referred to as 2-8-2 or ‘Mikado’ design, with four driving wheels on either side placed between a set of smaller non-driven wheels at the front and back. Those driving wheels were more than 2m in diameter, which gives an inkling of the engine’s massive scale. This arrangement allowed the firebox to be placed behind the driving wheels rather than on top of them, which meant the firebox could be much bigger than on other locomotives, so it could burn fuel faster, generate more steam and develop more power. The P2 was the only Mikado locomotive Gresley designed for passenger service.

Another important factor for the P2 steam engineers was that Gresley designed his locomotives with a great deal of commonality between classes, to reduce the amount of new design work and tooling for components, and to accelerate development time. As a result of this, it has 70 per cent commonality with the A1, which, in the shape of Tornado, the team has already built: large components such as the boiler (generating 250lb/sq in steam pressure) and tender are identical, as are many smaller parts and systems.

Despite this, the P2 included many engineering innovations. Allatt picked out as particular examples: the 50m2 firebox grate; the rotary cam poppet valve gear; the all-welded tender with spoked wheels; the arrangement of chimney and blast pipe; and the feed water heater. Of these, he added, the valve gear is probably the biggest challenge in engineering terms. The valves control the inlet and exhaust of steam into and out of the cylinders and were designed to work with superheated steam, to minimise maintenance and to work without the need for lubrication.

The P2 being built by Allatt’s team is to be named Prince of Wales, to commemorate the 65th birthday of Prince Charles: perhaps unsurprising considering his antipathy to modern technology, the Prince is a steam enthusiast and has already hired the Tornado to pull his personal train. But it won’t be a direct replica of any of the six previous P2s. Instead, it will be a new member of the class with its own specific designation; where Cock o’the North was P2 2001, Prince of Wales will be P2 2007.

There are several reasons for this, Allatt explained. The first is that Gresley’s original design was by no means perfect: its relatively short lifetime meant that the design was never fully developed or even used to its full potential. The engine had problems cornering, which were related to the design of the front truck; a redesign was done for a shorter locomotive and this will be applied to the new P2. Like Tornado, the new locomotive will use roller bearings throughout; and the coupling and connecting rods will be in graphite steel rather than the nickel steel used in the 1930s. Other changes from the original design are to allow the locomotive to run on the modern railway: this will include electronics to work with modern signalling systems and primary air brakes for the locomotive — the rest of the train would have vacuum brakes.

Prince of Wales will cost about £5m to build, which the P2 Steam Locomotive Company is raising via contributions from members. Fundraising is ongoing, but the project hit its first milestone last month with the production of the locomotive’s frame at the Tata steelworks in Scunthorpe; the frames were rolled and then profiled by a purpose-built Messer Omnimat profiling machine, which cuts steel using gas burners. The process was ceremonially initiated by Gresley’s grandsons, Ben and Tim Godley.

The resurrection of long-obsolete technology, no matter how impressive, will always invite an accusation of nostalgia over practicality, but Allatt is adamant that this is a valid engineering challenge. ‘We’re recreating a peak in the development of steam, as well as perpetuating steam-specific skills, which remain relevant,’ he said. The team is planning further projects to recreate some of Gresley’s ‘lost’ locomotive designs, which, like Tornado and Prince of Wales, will run on charter trains on the mainline and heritage lines

Red Bull makes hydrogen fuel cell play with AVL

Formula 1 is an anachronistic anomaly where its only cutting edge is in engine development. The rules prohibit any real innovation and there would be...