The factory floor and the operating theatre may seem worlds apart but, in reality, these two outwardly different environments face many common challenges. Both are time-pressured, often high-volume environments that rely on exacting precision, tight tolerances, repeatability and high levels of technical expertise.

And as manufacturing technology becomes ever more sophisticated, the developments driven by the insatiable demands of industry are increasingly finding application in the medical arena.

One company at the forefront of this fascinating crossover is Gloucestershire engineering firm Renishaw, which has exploited the know-how developed by its core manufacturing technology business, to establish a growing and successful presence in the healthcare technology sector.

Renishaw first entered the world of healthcare in the late 1980s, when it began using its measurement and scanning expertise to design and develop custom dental implants – an area of business that’s expanded over the following decades.

But while its dental work remains perhaps the best-known part of the firm’s medical division, it now boasts a much wider medical offering: including world-leading expertise in the production of bespoke implants, and a robotic system for neurosurgeons that’s helping to revolutionise the treatment and diagnosis of a range of conditions.

Opening up in South Wales

Last year, in a sign of the sector’s growing prominence in the firm’s plans, Renishaw opened a new Healthcare Centre of Excellence at its site in Miskin South Wales: which it acquired from Bosch in 2011.

Sharing the 461,000-square-foot site with a full production engineering facility and the UK’s only dedicated production line for making additive manufacturing machines, the new centre was established as a manufacturing base for the company’s medical products, as well as an education and training centre for the life sciences community.

Its striking centrepiece is a highly accurate mock-up operating theatre that it uses to help train surgeons in the use of some of its key technologies. And the star of the show is Neuromate, an image-guided robot based on technology acquired by the firm back in 2008 that’s primarily used to precisely position implants and electrodes in the human brain.

The robot consists of an articulated arm tipped with a mount for a surgical instrument. Driven by sophisticated surgical planning software loaded with 3D images of the patient’s brain, the system positions the surgical instrument above the skull, enabling the surgeon to precisely target the correct part of the brain and enter the organ at a carefully planned trajectory that ensures that no critical structures are damaged.

Now used in hospitals around the world, including seven in the UK, Neuromate is claimed to be both faster and more accurate the conventional manual techniques, which typically require a patient’s head to be fixed to a frame and depend on continuous use of manual measurement devices.

A key area of application for the technology is in deep brain stimulation (DBS) a process that involves the implantation of small electrodes that are then used to stimulate a particular part of brain. The procedure is increasingly used to treat neurological disorders such as Parkinson’s disease.

In the past, implantation of electrodes for DBS has typically required the patient to be awake so that surgeons can be sure they’re not damaging any critical structures. But according to Anna Ritchie from Renishaw’s Neurological Products Division, the accuracy of Neuromate allows this procedure to be performed under general anaesthetic.

SEEG procedure

Another application for which the technology is proving useful is stereoelectroencephalography (SEEG), a diagnostic procedure used primarily in the treatment of epilepsy. Similar to DBS, this involves the precise positioning of multiple electrodes deep into the brain. These electrodes can then be used to record the signals from the brain during an epileptic fit, enabling surgeons to pinpoint and remove the area of the brain responsible for the epilepsy. It’s a procedure that has a remarkable success rate – curing around 90 per cent of patients treated. And, according to Ritchie, the use of the robot both improves the accuracy of the process and radically reduces the amount of time it takes to place the electrodes in the patient’s brain.

The robot was recently used to carry out the procedure for the first time in the UK by surgeons at the University Hospital of Wales in Cardiff. The patient, who had been suffering up to six fits every day for the past 20 years, has reportedly been fit-free since the procedure was carried out in March 2017.

A third application area for the system, and one still at the clinical trials stage, is its use to implant a system for delivering medication directly to the brain.

Neurodegenerative diseases are particularly hard to treat with medication thanks to the protective role of the so-called ‘blood brain barrier’, but Renishaw has used Neuromate to develop an implantable system that can be used to inject drugs through an external port at the back of the head directly into different parts of the brain. Renishaw is currently working with pharmaceutical company Herantis on a clinical trial, using the system to deliver a drug called cerebral dopamine neurotrophic factor (CDNF) to patients with Parkinson’s disease.

‘Brain surgery’ has long been associated with notions of extreme precision, so one might imagine that the challenges of developing a system such as Neuromate represents something of a step up technology-wise for a firm more used to dealing with the manufacturing industry. But, according to Ritchie, it’s actually the opposite. “We’re typically trying to target something like a square millimetre, which for Renishaw is a country mile compared to the low level micron demands of the aerospace sector – the key thing is repeatability of process, targeting and getting to that target in the brain – that’s the challenge.”

Exploiting the benefits of 3D printing

While Renishaw’s heritage in industrial metrology has fed into its neurosurgical business, its expertise in additive manufacturing has helped drive advances in another area of its medical division – the design and additive manufacture of custom implants.

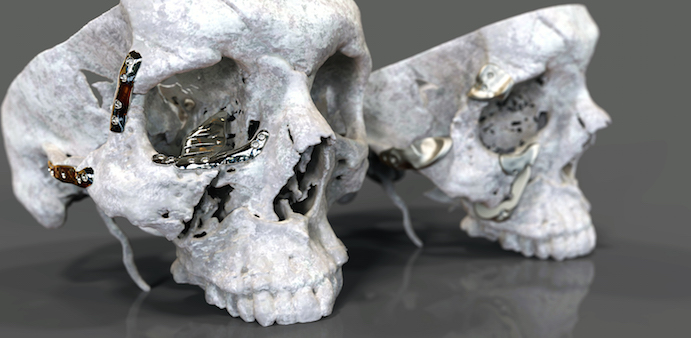

One particularly notable emerging area for the company is its use of 3D-printing technology to produce titanium maxillofacial implants.

Surgeons will typically provide Renishaw with CT data that will then be used to develop a design and produce parts that are sent back to the surgeon and fitted to the patient.

In one recent example, Renishaw collaborated with a surgeon involved in disaster relief in Nepal on the production of a 3D-printed orbital floor implant for a patient who had been injured in a road-traffic accident.

Orbital implants are particularly complex and sensitive structures, because of the proximity of the optic nerve. However, using CAD data supplied by the surgeons involved, Renishaw was able to produce a perfectly fitting implant in just one shot.

Ed Littlewood, marketing manager for Renishaw’s Medical Dental Products Division, said that while it is currently a relatively low-volume business, Renishaw is actively working to educate hospitals about the potential of 3D printing. One of the key challenges, he said, is persuading surgeons to adopt new technology: “It varies from surgeon to surgeon. Some are open-minded and keen to try out new technologies, others are more conservative.”

One notable way in which the company has helped to advance the uptake of the technology is through its ADEPT project – a winner at The Engineer’s 2016 Collaborate to Innovate Awards. This has led to the development of new software that makes it easier for surgeons to exploit the benefits of 3D printing.

Glasgow trial explores AR cues for autonomous road safety

They've ploughed into a few vulnerable road users in the past. Making that less likely will make it spectacularly easy to stop the traffic for...