According to the recent Engineering Skills for the Future Report by Semta, female engineers are more attracted to an interesting career rather than the salaries they will receive. But the Women’s Engineering Society reports that the UK still has the lowest percentage of female engineering professionals in Europe, at under 10 per cent. Emer McDonnell, a graduate at Air Products, considers whether female engineers could be the key to closing the skills gap.

According to the recent Engineering Skills for the Future Report by Semta, female engineers are more attracted to an interesting career rather than the salaries they will receive. But the Women’s Engineering Society reports that the UK still has the lowest percentage of female engineering professionals in Europe, at under 10 per cent. Emer McDonnell, a graduate at Air Products, considers whether female engineers could be the key to closing the skills gap.

It’s really surprising to me that women are so drastically underrepresented in UK engineering. But there’s a silver lining to every cloud and tackling this issue could present an opportunity for the industry to close the skills gap for good.

Personally, I really enjoyed physics, chemistry and maths at school. This was partly due to my school being very STEM-focused, which gave me a better insight into what a career in engineering might bring. My teachers helped me understand that I could combine my three favourite subjects at university and I went on to study Chemical Engineering at Queen’s University in Belfast.

I spent three years as an undergraduate before securing a one-year placement at Air Products working as a Customer Engineer in the company’s R&D labs in Basingstoke. During this placement, I was trusted to work on equipment used by customers and apply my knowledge to real problem-solving. At first, I wasn’t sure what to expect, but having the chance to apply what I’d learnt in the classroom to real life scenarios was fascinating and it’s the reason why I chose to pursue a career in the industry.

After my one-year placement, I went back to university for a final year to achieve my Masters and returned to Air Products to enter its graduate scheme. For each of the first five years, I’ll rotate into a different job role to get a full understanding of how the business works.

What always surprises me in all of this is while the majority of boys on my course at university went into finance and banking, nearly all the girls went into the engineering sector.

It’s only my perception, but in my experience women who study STEM subjects are more likely than men to pursue STEM careers. In other words, by encouraging more women to study engineering, we could be making a major indent on the skills gap. So the question is how?

For me it was critical that I understood what a career in STEM could be like early enough to choose the right subjects at A Level. I find even now my friends think my job must be limited because it’s never been made clear to them how much scope a career in chemical engineering can offer; it sounds vocational and probably a bit boring as well. When I explain what a career in chemical engineering actually involves, they’re infinitely more interested – sometimes I wonder how different their lives would have been if they knew what they know now when they were 16.

That’s why I was involved in an outreach program that saw me promote STEM careers to high school pupils while I was at university and I’m now glad to be continuing this work as a Science Ambassador.

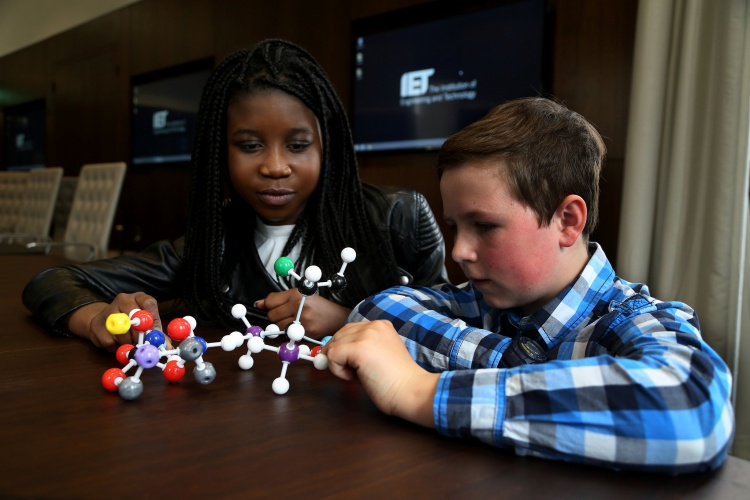

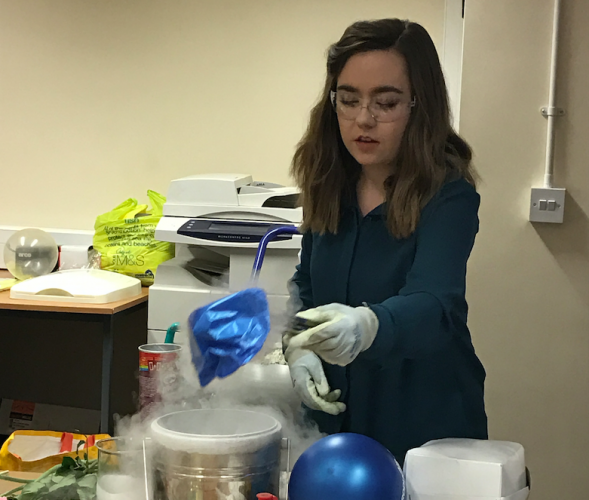

We visit schools to perform liquid nitrogen demonstrations and excite young students about science, attend careers fares to share the opportunities the company can offer with the next generation of engineers, and hold interview days to help students with employability skills.

As part of the Science Ambassadors national programme, Air Products provides 70 experts, 40 per cent of which are women. I think it’s really important that girls meet female engineers like me and other women in industry so they can see that STEM is so much more than a boys’ club.

I think this kind of action could be what’s needed. The industry should reach out to girls while they’re still at school to show them exactly what kinds of careers are on offer. I’m convinced this will be critical to closing the skills gap and ensuring the industry’s future. The alternative risks missing out on half a generation of talent.

April 1886: the Brunkebergs tunnel

First ever example of a ground source heat pump?