The inventors of the Searaser, an ocean-based pump that drives an onshore hydro-electric turbine, claim it can generate electricity at a rate of 1.5p per kWh – less than a quarter of the cost of other renewable sources and even lower than coal, gas or nuclear.

Dartmouth Wave Energy, the firm behind the device, says the device is so simple to construct and maintain that it will only cost around £200,000 per unit, with a total capital cost of £1.2m per MW.

‘It only has four moving parts so is much better able to stand the rigours of being deployed at sea,’ Dartmouth director Geoff White told The Engineer.

‘It doesn’t need any oil or lubricants because it’s lubricated by water. Maintenance is like that of a navigation buoy – you just need to lift it out of the water once a year and clean it.’

While White acknowledged the figures represent a bold claim, he said they are based on prototype trials and aren’t just a forecast.

‘We have to prove the commercial viability and the numbers may change when we scale up, but all the technology except the pump itself is already proven,’ he said.

Dartmouth hopes the Searaser will eventually produce around 1MW of electricity and has already attracted joint venture investment from green energy company Ecotricity.

But the device is still in the early stages of development – current output is around 100kW – and long-term testing is needed to see how it will fare in the harsh ocean environment.

Other companies pursuing a similar idea don’t claim to be able to operate anywhere near as cheaply as Dartmouth. Aquamarine Power, for example, expects its Carbon Trust-backed “Oyster” device to eventually generate up to 1MW for 8-9p per kWh, a cost more comparable with that of offshore wind.

The Oyster is much larger than the Searaser and has more a complex design. But its designers have the advantage of more experience and more data to back up their claims, with the first device in operation since last summer and the third generation model already on the drawing board.

There are also many challenges the sector still has to face before becoming commercially viable, according to Stephen Wyatt, head of the Carbon Trust’s Marine Energy Accelerator programme.

‘For example, you’re competing with the oil and gas industries for vessels and divers and you’re restricted in the time you can go out to sea, so it can cost a fortune to change a very cheap component if it goes wrong,’ he said.

Managing the higher water pressure further offshore, getting permission from marine authorities and finding suitable locations close to National Grid connections are other issues to overcome.

Aquamarine’s CEO Martin McAdam, argues firms in the wave sector would benefit more from cooperation than competition at this early stage.

‘There needs to be more shared learning and more honesty in the industry and there has to be a critical look at the performance of different machines,’ he told The Engineer. ‘We need fewer outlandish claims and more companies to share their failures and successes.’

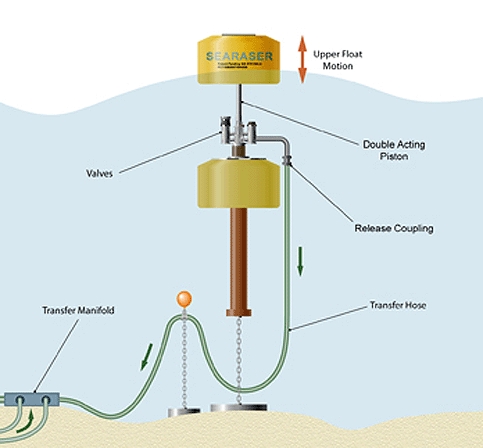

The Searaser concept explained

Hydro energy for the production of electricity is the next most efficient energy source (after nuclear) and has advantages over direct wind systems in being storable and controllable.

Most hydro systems in the western world have been exploited to their full potential, which means that future demand will not be satisfied by hydro unless new hydro energy forms become available.

Moving water to higher ground or to a hilltop facilitates a controllable hydro system similar to the Welsh and Scottish pumped storage systems but utilising renewable energy and not fossil fuels to pump the water up to the head.

Searaser uses wave displacement to lift a float attached to a piston and uses gravity in the wave’s following trough to push the piston back down. It is different from other devices as it is tethered to a weight on the seabed by a single flexible tether, but utilises a double acting piston, thereby producing volumes of pressurised water in both directions of the piston.

Incorporated in the design of the Searaser pump is an adjustable hydraulic column platform which adjusts itself and locks to any height of the tide.

The device has a wave (or swell) pump to pump sea water to a hilltop. It uses the energy of the water in which it floats to pump the stored potential energy.

If high ground is not available or unsuitable for storing the water for the turbines, the pressurised water pumped via an accumulator direct from the waves will be of sufficient pressure to drive the turbine generators near sea level. These are based on land or offshore rigs, or afloat.

Source: Dartmouth Wave Energy

Nanogenerator consumes CO2 to generate electricity

Whoopee, they've solved how to keep a light on but not a lot else.