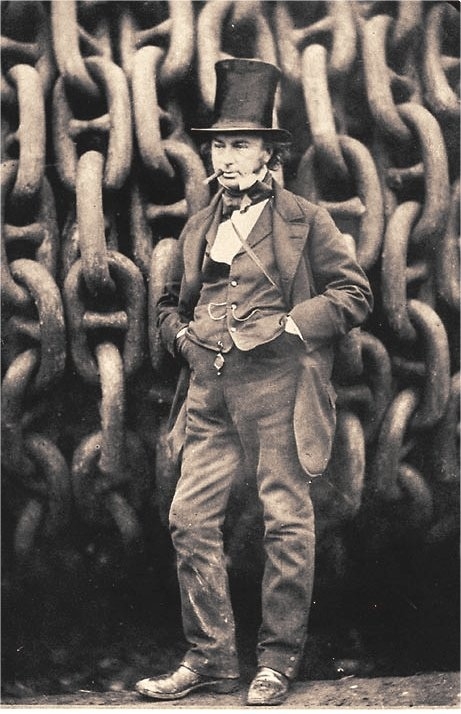

More than 150 years after his death Isambard Kingdom Brunel remains one of the few engineers that most British people can name.

Revered alike by Industrialists, politicians, media and the general public he regularly tops lists of “Great Britons”, is frequently held up as an example of the qualities missing from modern Britain, and even played a starring role in the recent Olympics opening ceremony

But as the Obituary that appeared in The Engineer following his death in Sept 1859 illustrates, a man regarded by many today as the greatest engineer that ever lived was viewed very differently by at least some of his contemporaries.

Mr Brunel was almost uniformly unsuccessful

Dwelling on a number of projects that it asserts were failures, the article describes Brunel’s career as “unfortunate”, writing that ‘notwithstanding the number and imposing character of his works many of them, often indeed through no fault of his own, have proved unsuccessful.’

His celebrated bridge over the Thames at Maidenhead - today in the running to be considered a world heritage site - is described as “bold, but unsuccessful”, while the Great Western Railway - routinely held up us one of the marvels of the Victorian age of innovation - is described as remarkable for its high cost rather than “any merits which it may possess as a work of engineering.”

Brunel’s shipbuilding efforts come in for a bit more praise. On his championing of screw propulsion for the SS Great Britain the magazine wrote that “Mr Brunel never allowed himself to overlook any new discovery giving promise of value in its application to engineering. Being in a position to exercise considerable influence he did not hesitate to employ it in introducing the new means of propulsion which has wrought such a marked change in the construction and working of our ocean steam marine.’

The article also contains a valuable lesson for today’s politicians and businesses, who increasingly struggle to justify investment in projects with little short-term economic pay-off. ‘He seized upon, modified and carried out many valuable discoveries which came before him and in this way often gave them a value which they would not otherwise have possessed. Judged by another standard, that of the financial results of the vast sums of money the expenditure of which he controlled, Mr Brunel was almost uniformly unsuccessful.’

Brunel was reportedly a friend of The Engineer’s founder Edward Charles Healey, so it seems unlikely that the paper would have an axe to grind. But after reading the article’s damning analysis of his personality its hard to escape the feeling that the maverick engineer had managed to upset someone on the editorial team. ‘He did not seek, in proportion to his opportunities, to raise those beneath him, and comparatively few men enjoyed his confidence,. He often managed to quarrel with his contractors. He had little sympathy for struggling genius, he seldom lost an opportunity for decrying against inventions and inventors not withstanding that his reputation was largely due to the applications which he had made of the ideas of others.’

Project to investigate hybrid approach to titanium manufacturing

What is this a hybrid of? Superplastic forming tends to be performed slowly as otherwise the behaviour is the hot creep that typifies hot...