According to Jeffrey Siewerdsen, Ph.D., a professor of biomedical engineering at Johns Hopkins, there are up to four incidents of “wrong-level” spine surgery per week in the US, a situation that can arise because the spine is made up of repeating elements that look alike.

However, results from its first clinical evaluation show that LevelCheck software achieves 100 per cent accuracy in 26 seconds. Details of the study will appear in the April 15 issue of the journal Spine.

Surgeons go to great lengths to get their procedures right, because mistakes are costly to patient health. They can result in pain, require follow-up surgeries, and create instability or degeneration of the spine, said to Jean-Paul Wolinsky, M.D., an associate professor of neurosurgery and oncology at Johns Hopkins and co-author of the study.

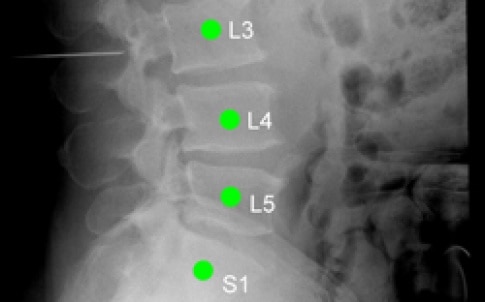

According to JHU, patients receive a diagnostic CT or MRI scan before a standard spinal operation that the surgeon uses to plan the surgery. Once the patient is on the operating table the surgeon typically counts down from the skull or up from the tailbone to determine which vertebra to operate on, often marking the patient’s anatomy with thin metal pins. These pins are visible in an X-ray image taken in the operating room to verify the target site. But the doctor’s initial planning on the preoperative scan is not visible in the X-ray image, leaving room for error, particularly when working on challenging cases exhibiting missing or extra vertebrae, a loss of anatomical landmarks from previous surgeries, or other anomalies.

LevelCheck uses a standard desktop computer outfitted with a graphics-processing unit to align a patient’s 3D preoperative CT image with the 2D X-ray image taken during surgery. The result is an X-ray image showing the pins that act as landmarks for the surgeon, overlaid with the planning information from the CT scan.

“LevelCheck does not replace the surgeon’s expertise. It offers helpful guidance and decision support, like your GPS,” Siewerdsen said in a statement.

To test its accuracy, the team analysed pre- and intraoperative images of 20 consecutive patients who had undergone spine surgery. By shifting the images, they simulated 10,000 surgeries and measured how long the software needed to correctly line up the images 100 per cent of the time.

“This study is the first to demonstrate that LevelCheck works with real patient images,” said Siewerdsen. “It shows that the software can deal with challenges like changes in patient anatomy and the presence of surgical tools in the X-ray image.”

Sheng-Fu Lo, M.D., evaluated the results to find what factors can cause the software to fail. “The software doesn’t always get it right if it is stopped early, but given 26 seconds or more, LevelCheck found the right level every time.”

Wolinsky said: “We can’t eliminate the possibility of wrong-level surgeries but this is an additional level of security — an independent check — that works quickly within our standard surgical workflow. Although LevelCheck in its current form requires a preoperative CT scan for most patients, the benefit is well worth it.”

Project to investigate hybrid approach to titanium manufacturing

What is this a hybrid of? Superplastic forming tends to be performed slowly as otherwise the behaviour is the hot creep that typifies hot...