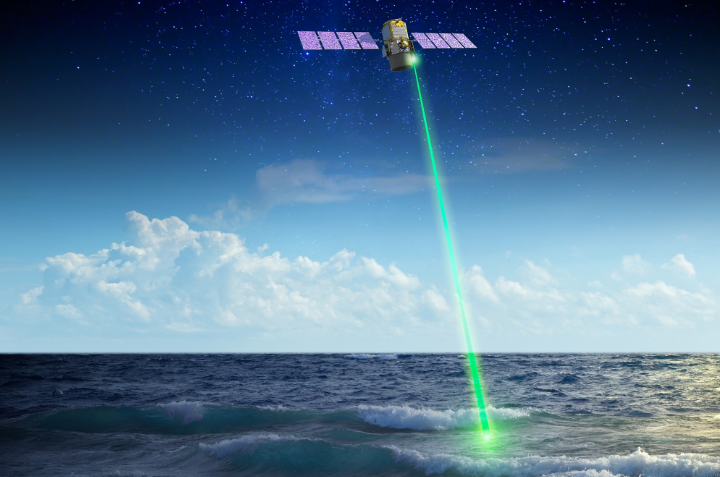

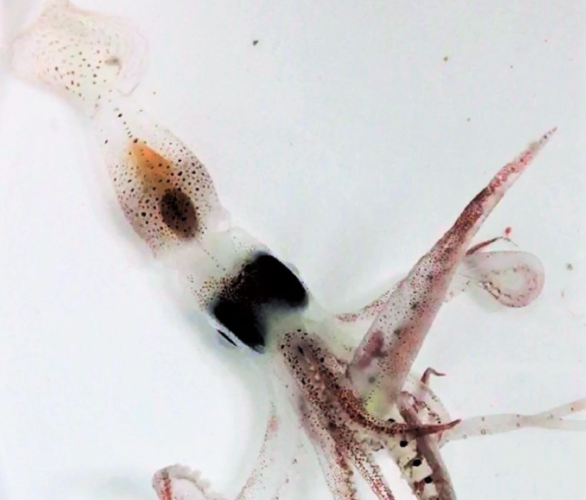

The Cloud-Aerosol Lidar and Infrared Pathfinder Satellite Observations (CALIPSO) satellite is a joint venture between NASA and the French space agency, Centre National d'Etudes Spatiales. Shortly after its launch in 2006, it was discovered that as well as observing cloud aerosols, CALIPSO was able to monitor the oceans to a depth of 20m. This allowed it to track Diel Vertical Migration (DVM), where tiny sea creatures like krill, baby fish and tiny squid move closer to the ocean surface at night to feed on phytoplankton.

UK space: A new world of opportunity

Space radar technique reveals Morandi Bridge deformation

“This is the latest study to demonstrate something that came as a surprise to many: that lidars have the sensitivity to provide scientifically useful ocean measurements from space,” said Chris Hostetler, a scientist at NASA's Langley Research Centre in Virginia, and co-author of the study, which appears in Nature.

"I think we are just scratching the surface of exciting new ocean science that can be accomplished with lidar.”

DVM is the planet’s largest migration by biomass and as such has wider implications for ocean ecosystems, fishing stocks and even climate change. Phytoplankton absorb carbon dioxide via photosynthesis. When zooplankton like krill and tiny fish migrate to the surface to feed on it, much of this carbon is then sequestered deep in the ocean when the creatures defecate or die. This animal-mediated carbon conveyor belt is recognised as an important mechanism in Earth’s carbon cycle.

"What the lidar from space allowed us to do is sample these migrating animals on a global scale every 16 days for 10 years," said Mike Behrenfeld, the lead for the study and a senior research scientist and professor at Oregon State University in Corvallis, Oregon. "We've never had anywhere near that kind of global coverage to allow us to look at the behaviour, distribution and abundance of these animals.

"The new satellite data give us an opportunity to combine satellite observations with the models and do a better job quantifying the impact of this enormous animal migration on Earth’s carbon cycle."

Project to investigate hybrid approach to titanium manufacturing

What is this a hybrid of? Superplastic forming tends to be performed slowly as otherwise the behaviour is the hot creep that typifies hot...