When it comes to cutting carbon emissions there’s an argument that we should start with the relatively simple measures and, where possible, use available resources within the confines of existing infrastructure.

Energy efficiency measures, renewable heat and waste-to-energy schemes broadly fit into this regime and seem to be gaining ground of late with the help of some good old carrot and stick philosophy.

This week the £860m renewable heat incentive (RHI) was officially opened up to applications. It is hoping to result in 126,000 installations and save 43 million tonnes of carbon by 2020.

The scheme will be open to businesses first before the domestic sector – although the existing Renewable Heat Premium Payment scheme, providing money off renewable heat technologies for householders, is open until March 31 next year.

Meanwhile, the Green Deal – details of which were announced last week – plans to refurbish the UK’s old and draughty homes with £200m of incentives.

Housholders will be able to take out loans of up to £10,000 over a 25-year term for things like insulation and will be offered up to £150 cashback in order to encourage participation.

Sticks play a large part as well, in the form of ever-rising energy bills for homes as well as EU landfill taxes for councils and businesses. Occasionally though there’s the need to provide a more direct nudge as well.

The Mayor of London quite rightly overturned a decision recently by the Borough of Merton council which rejected an anaerobic digestion plant, branded ‘ugly and uninspiring’ by opponents. Indeed, the facility has the potential to provide those very objectors with power equivalent to the output of 1800 homes a year from 40,000 tons of refuse.

Incidentally, by the end of the year, Sainsbury’s is aiming to become the first supermarket to send all its food waste for anaerobic digestion (AD).

Still, companies, institutions and organizations can go even further with established technology to make their operations more efficient.

This week I attended the unveiling of an aquifer thermal energy storage (ATES) scheme which hopes to serve as a model to be rolled out across government estates in London.

The project is being drawn up by contractor Mott MacDonald for the 1851 Group which includes the Natural History Museum, Imperial College, the V&A, the Science Museum, the Royal Albert Hall, the Royal College of Music and the Royal Geographical Society.

It envisages an underground heating and cooling network beneath Exhibition Road in South Kensington linking some of the buildings occupied by the above list of prestigious institutions – which last year had a combined utility carbon footprint equivalent to five major hospitals.

The thinking behind it is that the Victorian buildings such as NHM require inordinate amounts of energy to heat while more modern buildings such as Imperial College with all its world-class technology research require constant cooling.

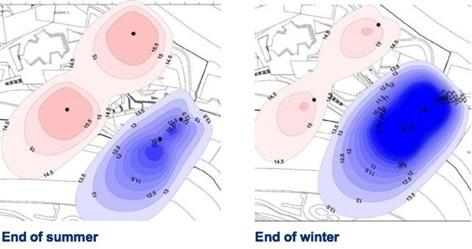

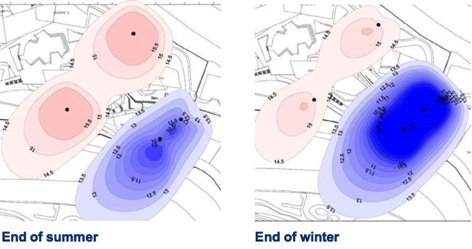

Drills will bore 70m down into the saturated chalk aquifers which will store heat during the summer for subsequent winter cooling and cool water in the winter for later summer cooling. The project envisages 3 boreholes at one extreme end of the site for the ‘warm well’ and 3 bore holes at the other end of the site for the ‘cool well’. In the Summer, for example, water at around 10-15°C would be drawn from the cool well passed through a heat exchanger connected to a heat pump and usedfor cooling, then discharged at a temperature of 15-20°C for storage in the warm well.

Mott MacDonald hopes to make use of the existing Victorian network of tunnels, where possible, for shunting water back and forth. Although similar schemes exist elsewhere, notably in the Netherlands, the project will be the largest of its kind in Europe.

It has yet to secure the required £32 million funding for capital costs, but around £3m has been spent to develop the plans through the Treasury’s Invest to Save scheme. It has required quite some effort to get all the institutions on board with the scheme, who although part of the 1851 group are very much separate entities with their own visions (even mong the individual museums).

And that’s the challenge. Much of London is sitting on this layer of chalk aquifer which crops out at the Chilterns and the Devon coast, and has the potential to make our capital, with its unique mix of historic and modern buildings, more efficient. But it will take some joined-up thinking being demonstrated by 1851 to make it happen.

Glasgow trial explores AR cues for autonomous road safety

They've ploughed into a few vulnerable road users in the past. Making that less likely will make it spectacularly easy to stop the traffic for...