What’s often missing for a successful product?

The short answer: emotional content.

I was at the Manufacturing Summit at 1 Bird Cage Walk a few years ago listening to the success stories of some of the show case British manufacturers, when it occurred to me that a piece of the story wasn’t being explained properly.

The first company, I remember, had developed a metal detector door portal used by hospitals to prevent any metal objects being brought into an MRI scanning room. Apparently watches, instruments, and even wheel chairs have been inadvertently brought within range of the magnetic field and required a crow bar (and possibly a traction engine!) to remove them. The study talked about the technical capability, the IP and the supply chain and so on, but it struck me that the physical design of the product was attractive and elegant. This aspect seemed to be taken for granted. It had real emotional value. I never did the analysis, but it would have been interesting to see if the competitors of this successful product were quite different in look and feel.

Emotional value has been one of the biggest changes in the way that people purchase things over the last 30 years. In particular, consumers often purchase products such as branded FMCG and technology goods largely based on emotional value. In his book, Thinking Fast & Slow, Daniel Kahneman explains the two systems active in the human mind which drive the way we think and make choices. One system is fast, intuitive and emotional and the other is slower, more deliberative and logical. Both systems are busy working in the background of the usually oblivious consumer’s mind. We think the logical system is making the decisions, but multiple studies show it’s the emotional fast system that’s really often in charge.

The second company I recall from the summit is Brompton, whose folding commuter bicycles have innovative functionality and designs, as well as over 20 patents. They also, crucially, generate enormous emotional value for their community of customers attaining near “cult status”. Their huge fan base even spends weekends on Brompton rallies and participates in 24 hour races with their folding premium commuter bicycles!

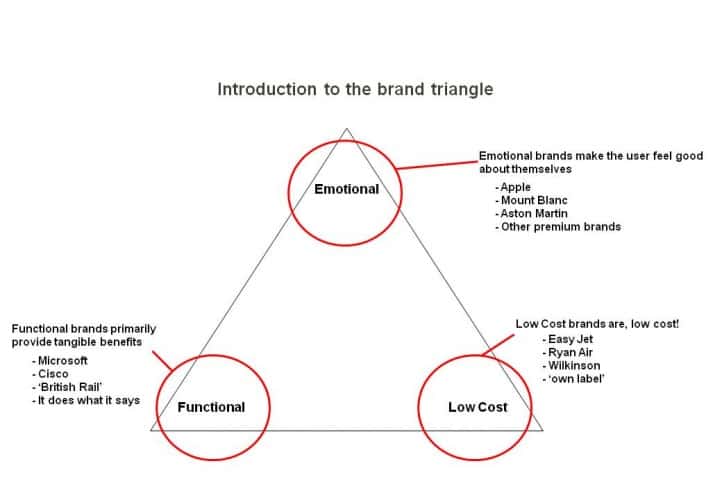

In other words, these products connect with peoples’ lives. The brand triangle is a useful tool to assess the value tradeoffs of a product. It was introduced to me by Dr Dipak Jain, who, as Dean of Kellogg School of Management, home of marketing guru Philip Kotler, took that school to a #1 ranking in the world.

The triangle is a map or 3 sided field (not a pyramid) with 3 corners: Emotional, Functional and Low Cost. Emotional products are bought by people because they make them feel good. Examples include most luxury products. Functional products do exactly what they say on the label but without any particular love. In the old days this would perhaps be British Rail, but perhaps Microsoft would sit here today. Finally, Low Cost products compete primarily on price. Examples here are discount stores and airlines. Products can be 100% in one of the ‘pure’ corners, or a mixture of 2 or 3 to varying degrees. By placing products in the triangle, marketers can assess or contrast where a product sits compared to its competition. It’s worth noting that a long string of failures have highlighted how difficult it is to survive for long in the Low Price corner, without structural advantages.

This analysis has its roots in consumer marketing, but it’s also applicable to business to business. Ultimately, professional buyers are human beings too, subject to emotional messages. Furthermore, organisations such as hospitals, with a public facing mandate, will wish to communicate the correct image and visual assurance messages in any case.

Of course, this is best epitomised by the Apple phenomenon. In workshops, when I ask people why they bought Apple, they are often unable to offer a rational reason that survives much scrutiny. Actually, it’s not the fact that they purchased Apple that’s most interesting; it’s that they paid a premium price. This is perhaps the reason why Apple currently has a cash pile of over $178,000,000,000, or about twice that of the US Treasury. I’ve written out the zeros long hand on purpose. Those zeros perhaps demonstrate, better than anything else, the fruits of getting the emotional value right within the selling proposition.

Nanogenerator consumes CO2 to generate electricity

Whoopee, they've solved how to keep a light on but not a lot else.