Engineers from the Bendable Electronics and Sensing Technologies (BEST) group at Glasgow University have developed a new type of flexible supercapacitor which is said to replace the electrolytes found in conventional batteries with sweat.

Graphene-based wearable supercapacitor powers prosthetic hand

Human sweat-powered e-skin points to future robotics

They said it can be fully charged with 20 microlitres of fluid and is robust enough to survive 4,000 cycles of the types of flexes and bends it might encounter in real-world use. A paper detailing the research, funded by EPSRC and the Royal Society, is published in Advanced Materials.

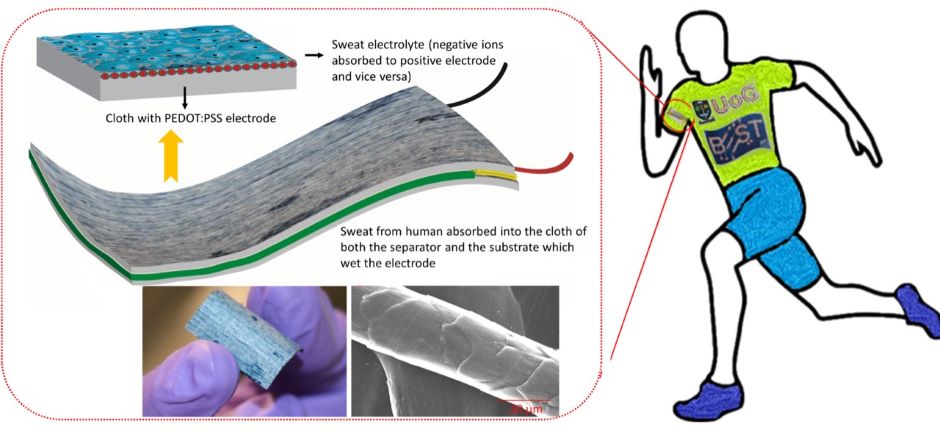

It works by coating polyester cellulose cloth in a thin layer of poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) polystyrene sulfonate – or PEDOT:PSS, which acts as the supercapacitor’s electrode. Polyester cellulose cloth is particularly absorbent, and PEDOT:PSS offers flexibility, high conductivity and environmental friendliness.

As the cloth absorbs its wearer’s sweat, the positive and negative ions in the sweat interact with the polymer’s surface, creating an electrochemical reaction which generates energy.

To test the device, volunteers ran outdoors and on a treadmill while wearing a 2cm x 2cm cell version of the device. The runner sweated enough to allow the device to generate about 10 milliwatts of power – about enough to power a small bank of LEDs – which kept it going until the runner stopped.

The research was led by Prof Ravinder Dahiya, head of the BEST group, based at the Glasgow University’s James Watt School, of Engineering.

In a statement, Prof Dahiya said: “Conventional batteries are cheaper and more plentiful than ever before, but they are often built using unsustainable materials which are harmful to the environment. That makes them challenging to dispose of safely, and potentially harmful in wearable devices, where a broken battery could spill toxic fluids onto skin.

“What we’ve been able to do for the first time is show that human sweat provides a real opportunity to do away with those toxic materials entirely, with excellent charging and discharging performance.

“As wearable devices like health monitors continue to increase in popularity, it opens up the possibility of a safer, more environmentally-friendly method of generating sustainable power – not just for wearables but possibly also for emerging areas such as e-bikes and electric vehicles, where sweat equivalent solution could replace the human sweat.”

Prof Dahiya and his team at Glasgow University have developed a number of novel bendable technologies, including solar-powered ‘electronic skin’ which could be used in prosthetics and robotics. They are planning future research on the possibility of integrating sweat power into these devices.

Project to investigate hybrid approach to titanium manufacturing

What is this a hybrid of? Superplastic forming tends to be performed slowly as otherwise the behaviour is the hot creep that typifies hot...