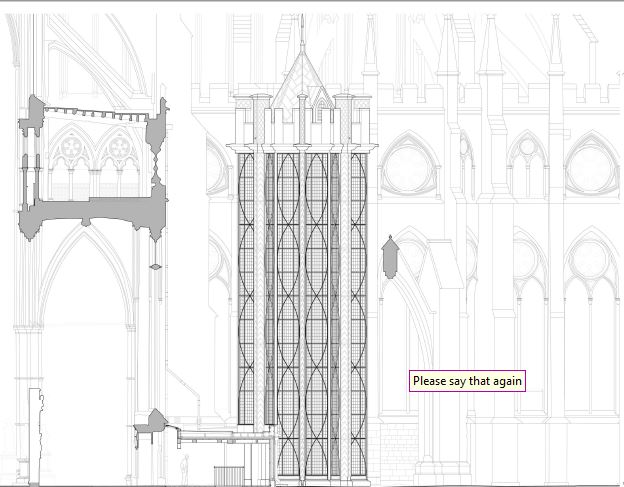

Being the only part of the new construction visible from the outside of the Abbey, no matter how well it blended in, the Weston Tower presented a particular type of challenge to the project team. Designing it was an iterative process between Ptolemy Dean Architects and structural engineers at Price & Myers.

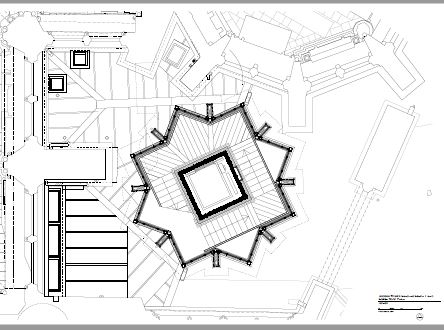

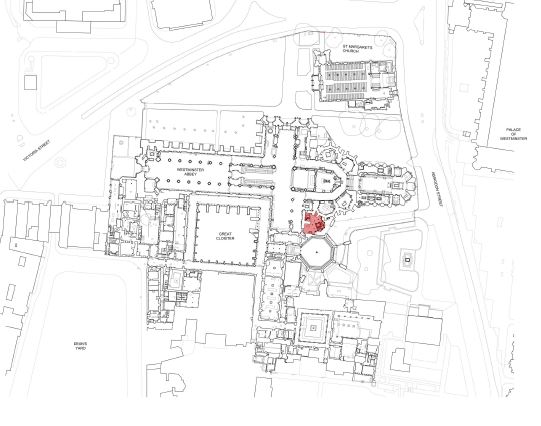

At the beginning of the project, the only aspect of the design that had been decided was its plan: the eight pointed star formed by two rotated squares, this shape echoing one of the gallery’s exhibits – the Westminster Retable, England’s oldest altarpiece, a thirteenth century masterpiece of painting on oak panels. “There was only one place on the outside of the Abbey the tower could go – that angle between the Chapter House and the Henry VII Chapel – so we knew from the beginning we wouldn’t have much space,” said Sam Price, co-founder of Price & Myers.

Stone or steel?

Despite this, there were originally ideas to build the tower out of stone. “But that just wasn’t going to happen,” said Price and Myers associate Fiona Cobb. “It quickly became evident that we would have to make the footprint of the tower as small as possible, and that led us back to a slim concrete lift shaft with steelwork supporting the outer edges of the floors and stair.” This led to the concept of using the glass tower almost as a museum display case in reverse: instead of visitors looking at an exhibit from outside the case, the Abbey itself is the exhibit and visitors view it from inside the case.

“There was a question of what we were going to do about the foundations of the tower,” Cobb said. “We had no real idea of what the foundations of the Abbey were like, whether they went straight down or projected out from the base of the walls, or what state they would be in.” Extensive archeological investigations found that the foundations in fact stepped out from the wall in stages, which meant that a relatively shallow pit could be dug for the elevator shaft and standard poured concrete foundations made.

With the shape and construction materials decided, the internal layout next had to be determined. “Ptolemy just wanted a staircase wrapped around the lift shaft, and fortunately he didn’t want a spiral staircase around a round shaft,” Price commented. “Round lift shafts tend to be very expensive to construct, and in any case a circle inside that octagonal space wouldn’t have worked.” The square inside the eight pointed star is also awkward geometry, he said. “The external elements that support the tower connect to the square at slightly odd angles, but we made it work.”

Those external elements were originally referred to as buttresses. “They aren’t buttresses,” Price said. “Buttresses start out very thick at the bottom and step in as they go up. These are slightly thicker at the bottom and taper upwards, but really they are steel columns. Ptolemy likes to call them buttresses because it fits better with the Abbey.”

A skyscraper on a cathedral

The steel in the structure is painted and also protected by the layer of lead sheathing: an aesthetic choice, as it has been used for centuries to protect ecclesiastical buildings, but also a practical one, as it is very effective at keeping out moisture, always the enemy of historic structures. “It’s also a good choice for maintenance,” Price said. “When pinholes develop in church lead, what you traditionally do is protect the area while you strip it off, melt it down, cast and roll new sheets and put it back.”

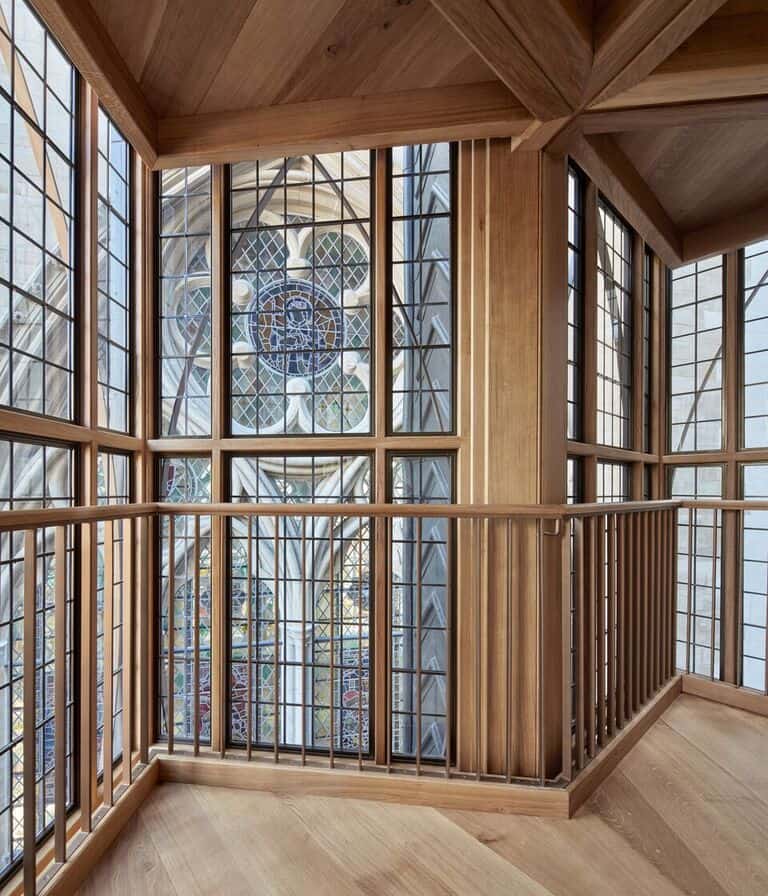

Inside the tower is a world of stone, glass and oak. “Ptolemy and I both wanted English oak, but we were told we would never get pieces big enough and would have to use French. There’s lots of French stone in the Abbey, but I still wanted English if possible. Fortunately, the builder Daedelus Construction found a timber yard with marvellous English oak, and it was cut to minimise any distortion in the wood as it ages,” Price said. “It will change shape, because wood always does, but it should remain stable.” Up in the triforium, it seems that Christopher Wren faced similar issues, and his five-century old timbers are certainly in good shape.

The glass curtain walls of the Weston Tower, like all glass walls, are not load-bearing. In this sense, the tower has something in common with skyscrapers: it is supported by its steel column frame and the walls hang down. At the top of the columns, an octagonal ring beam forms the base of the crown-shaped pinnacle and the rest of the construction effectively hangs off this. “This means that a lot of the structure is in tension rather than compression,” Price said. “That’s an advantage, because when steel is in compression you can have problems with slenderness.”

All towers have to deal with the effects of wind, and the Weston Tower was no exception. Price & Myers asked the Building Research Establishment near Watford for assistance, and a scale model of the Abbey and its surrounding buildings was constructed for testing in BRE’s wind tunnel. “Fortunately, the Abbey Shields the tower from most of the wind,” Cobb said. “It receives only a fraction of the rest of the building.”

Being a public building, the design also had to be assessed for resistance to blast in case of terrorist attack. The glazing in the tower’s walls is based on Christopher Wren’s scheme in the adjacent parts of the building, consisting of rectangular panels within a lead grid. On testing, the full details of which remain classified for security purposes, this design turned out to be surprisingly resilient.

Test of time

The longevity of the structure is one of the unknown of the project. “The building codes say it should survive for 50 years, but of course we are aiming for much longer than that,” Cobb said.

“We are using materials like steel, seasoned oak, concrete, glass and lead, and historically we know those last pretty well,” Price added. “As long as moisture stays out, I’ve got no reason to think it wouldn’t last for a lot longer.”

The incredibly high standard of workmanship in the tower is one of the most obvious things any visitor will notice. “Nobody working in these surroundings would want to give anything other than their very best,” Price said.

Glasgow trial explores AR cues for autonomous road safety

They've ploughed into a few vulnerable road users in the past. Making that less likely will make it spectacularly easy to stop the traffic for...