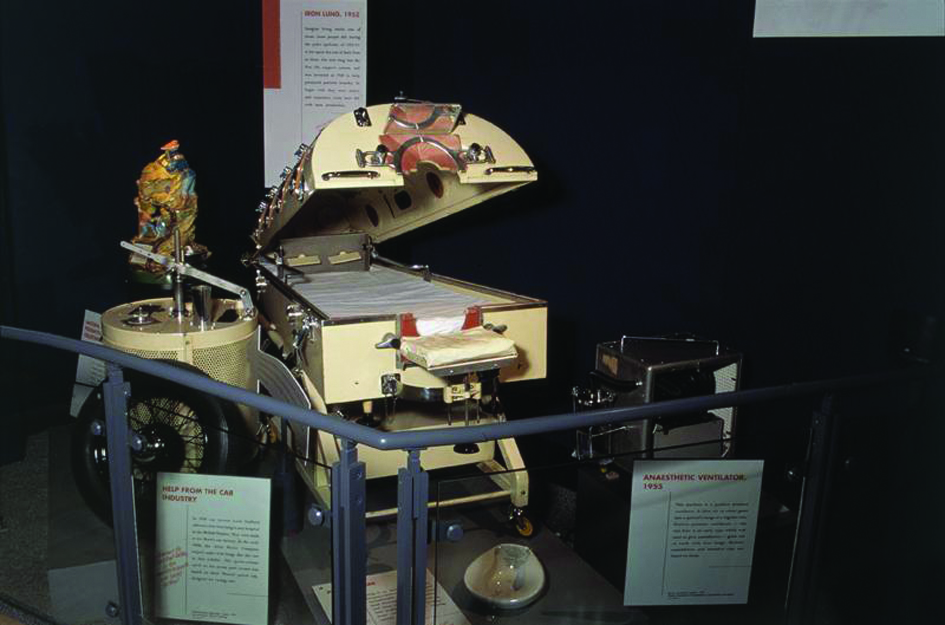

Reading back through the archives of The Engineer can give some startling insights into how our world has changed: quickly in some ways, slowly in others. For example, it’s quite startling to see in an issue from the late 1950s, well within the lifetime of many of our readers, detailing improvements in the designs of mechanical breathing machines — better known as iron lungs — to help with the epidemics of polio which occurred every summer.

Indeed, 1956 — the year of this article — had been a bad year, with epidemics in Ireland and the Netherlands. The vaccine which has eradicated the disease in the industrialised world and come close to wiping it out worldwide has been developed by Jonas Salk only a few years previously and was still in trials. Polio was feared everywhere and with good reason: it killed and crippled hundreds, mostly children, every year.

The article in The Engineer was taken from a lecture given by Captain George Smith-Clarke, who had been chief engineer at British car manufacturer Alvis from 1922 to 1950, and had designed cars which won races at Brooklands and Le Mans. In 1952, he had taken on the chairmanship of the Coventry and Warwickshire Hospital board of management, and as part of this role he’d been asked to look at the engineering of mechanical ventilators.

He wasn’t impressed.‘Some may think, as many patients have done, that it had a very uncomfortable resemblance to a coffin, and for this reason screens were sometimes placed around it so that patients could not see it when being put in.’ Upset at the distress he’d seen in children being taken out of iron lungs, he redesigned the machine used most at the hospital, the Nuffield-Both machine, which had been in use since 1939.

‘I took over a disused air-raid shelter in the hospital grounds and with the help of the senior physicist and a member of his staff, a Nuffield-Both machine was completely dismantled,’ he recalled in his lecture. ‘It was found impossible to obtain working drawings and I had to make dimensional free-hand sketches.’ Alvis made the castings for the larger parts, while Smith-Clarke himself machined the smaller parts needed.

As well as making the machines more controllable and efficient at helping patients to breathe, Smith-Clarke also thought it important to make them more comfortable. He included more ports in the side of the machine, so the patient could be reached for nursing care without affecting breathing. He also designed better head-rests and stretcher support system. Smith-Clarke later helped Alvis employees to set up a company to supply kits to modify breathing machines.

Poll: Should the UK’s railways be renationalised?

Rail passenger numbers declined from 1.27 million in 1946 to 735,000 in 1994 a fall of 42% over 49 years. In 2019 the last pre-Covid year the number...