Anybody visiting Parliament Square at the moment will see a lot of disappointed tourists. One of the main things they will have come to see – the clock tower of the Houses of Parliament, universally (but erroneously) known as Big Ben – is sheathed in scaffolding with only one face of the clock visible.

And if they were hoping to hear the famous Westminster chimes, and the bell that is actually called Big Ben ringing out the hours, then they are also unlucky. Owing to essential repairs, the tower will be sheathed and the chimes silenced until 2021, apart from on special occasions such as New Year’s Eve.

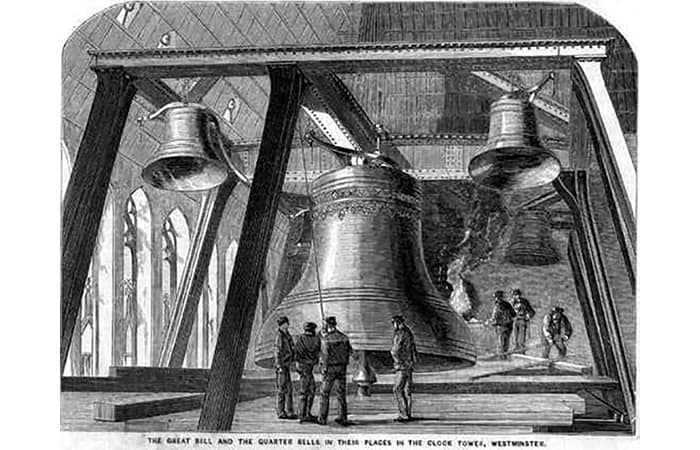

Perusing our archive, we came across a small entry – just one paragraph – full of interesting and very little known facts about the bell. The first eye-catching thing was that it was referred to as “Big Ben the Second”. There are no further details on why this should be so in the article itself, but a little research has uncovered some history.

Register now to continue reading

Thanks for visiting The Engineer. You’ve now reached your monthly limit of premium content. Register for free to unlock unlimited access to all of our premium content, as well as the latest technology news, industry opinion and special reports.

Benefits of registering

-

In-depth insights and coverage of key emerging trends

-

Unrestricted access to special reports throughout the year

-

Daily technology news delivered straight to your inbox

UK Automotive Feeling The Pinch Of Skills Shortage

Aside from the main point (already well made by Nick Cole) I found this opinion piece a rather clunking read: • Slippery fish are quite easy to...