May 1949: The Boulton Paul Balliol

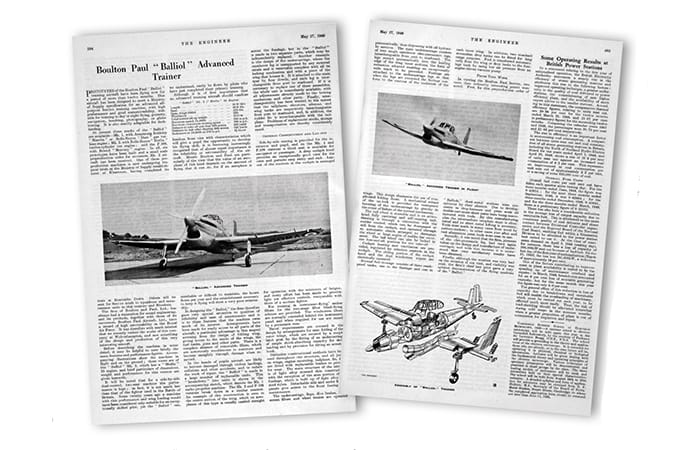

The Boulton Paul Balliol had just about everything the RAF and Fleet Air Arm could want from an advanced trainer, writes Jason Ford

Specifications defined by the Ministry of Supply asked for an all-purpose service training platform with high performance and good manoeuvrability. It had to be suitable for training in day or night flying, gunnery, navigation, bombing, photography, or glider towing. Finally, the new aircraft had to be ‘readily adaptable for deck landing’.

Boulton Paul Aircraft Ltd delivered on the specs with the design of three Balliol variants, namely the Mk. l with an Armstrong Siddeley Mamba or Rolls-Royce Dart gas turbine engine; the Mk. 2, with a Rolls-Royce Merlin twelve-cylinder vee engine; and the P.l08, with a Bristol Mercury engine.

By the time The Engineer visited the company’s facilities in Wolverhampton, six prototypes had been built and a small-scale preproduction order for 17 Mk. 2 aircraft had been received. In the air, the aircraft was said to perform as well as the British fighters that took part in the Battle of Britain.

Register now to continue reading

Thanks for visiting The Engineer. You’ve now reached your monthly limit of premium content. Register for free to unlock unlimited access to all of our premium content, as well as the latest technology news, industry opinion and special reports.

Benefits of registering

-

In-depth insights and coverage of key emerging trends

-

Unrestricted access to special reports throughout the year

-

Daily technology news delivered straight to your inbox

Water Sector Talent Exodus Could Cripple The Sector

Maybe if things are essential for the running of a country and we want to pay a fair price we should be running these utilities on a not for profit...