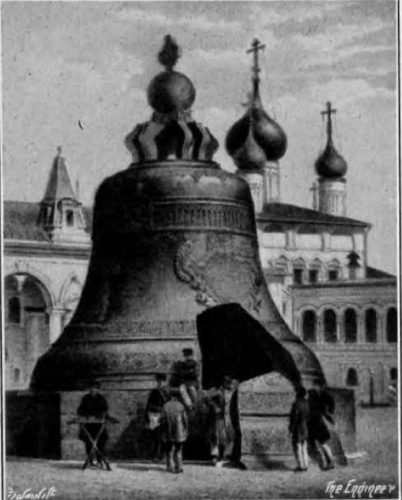

September 1939: The great bell of Moscow

The Engineer reports on a bell that captured the attention of Napoleon

The ill-fated Great Bell of Moscow (or Tsar Bell) is now a tourist attraction in The Kremlin, but for 103 years it sat gathering dust in a 33ft-deep pit into which it was cast in 1733 by order of the Empress Anna Ivanovna.

Ivanovna envisioned the Great Bell of Moscow as the successor to Tsar Alexis Mikhailovich’s 100-ton bell, which was destroyed by fire at the Kremlin in 1701.

The new bell was to be taller at 20ft 7in, have a larger diameter (22ft 8in) and weigh in at 200 tons. By 1737 it was being decorated with reliefs and had been hoisted above the casting pit to cool down when another fire broke out in the Kremlin, causing blazing rafters to fall on the bell. In their haste to rescue it, onlookers poured water onto the inferno, which caused the bell to crack and dislodge a piece that weighed 11 tons. The bell fell to the bottom of the pit and, in September 1939, The Engineer’s JR Nichols took a fresh look at the story.

Register now to continue reading

Thanks for visiting The Engineer. You’ve now reached your monthly limit of premium content. Register for free to unlock unlimited access to all of our premium content, as well as the latest technology news, industry opinion and special reports.

Benefits of registering

-

In-depth insights and coverage of key emerging trends

-

Unrestricted access to special reports throughout the year

-

Daily technology news delivered straight to your inbox

UK Enters ‘Golden Age of Nuclear’

The delay (nearly 8 years) in getting approval for the Rolls-Royce SMR is most worrying. Signifies a torpid and expensive system that is quite onerous...