Against a backdrop of the ongoing energy crisis, many feel that the case for nuclear in the UK is strong. While historically dividing opinion, nuclear power is widely hailed as a vital piece of the net zero puzzle.

Published in April, the UK government’s Energy Security Strategy highlighted its plans to meet the energy security challenge. The focus on nuclear was emphasised with the ambition of 24GW by 2050 representing what would be a quarter of the UK’s projected electricity demand.

Most stations within our current fleet, which comprises 14 Advanced Gas-cooled Reactors (AGRs) and one Pressurised Water Reactor (PWR) operated by EDF, are approaching the end of generating life with several already having ceased generation and entered defuelling phase.

With this in mind, new nuclear will be essential to hit net zero targets. Whilst build projects have been notoriously expensive and lengthy processes, new designs are looking to target some of these issues. Small Modular Reactors (SMRs), for example, could provide a cheaper and easier-to-deploy alternative to traditional large plant designs.

The Nuclear Financing Act, passed in March, will make it possible for nuclear projects to be eligible for funding through the Regulated Asset Base (RAB) model. The RAB model has been used in the UK for large-scale infrastructure projects including Heathrow Terminal 5 and the Thames Tideway Tunnel.

Through the RAB model, risk for developers is shared with consumers, who would begin paying toward the cost of a new nuclear build project through an addition to their bills during the construction phase. The charge to consumers would be set by Ofgem, acting as an independent economic regulator.

Government believes funding nuclear projects through the RAB model would result in better value for money and reduced cost for consumers across the plant’s life cycle compared to the Contract for Difference (CfD) model being used to finance Hinkley Point C. Currently under construction in Somerset, the EDF-led project represents the first new nuclear build in the UK for over 20 years and is scheduled to come online in mid-2027.

Through CfD, the cost of construction lies with the developer, who then charges a fixed ‘strike price’ once the plant is up and running. Consumers pay the difference between the wholesale electricity price and final strike price, but aren’t charged while the power station is under construction.

Whilst met with some concerns about cost overruns due to construction delays, the RAB model is intended to lower the cost of capital and the long-term impact on consumers by sharing costs from the beginning and reducing interest owed on loans. According to BEIS, the estimated cost saving for consumers will be between £30bn and £80bn through the RAB model in comparison to a CfD scheme.

Following the Energy Security Strategy, government launched the Future Nuclear Enabling Fund, setting aside £120m for new nuclear technologies. It aims to support the strategy’s target of eight new UK reactors by 2030. A new governmental body, Great British Nuclear, has been established to help bring projects forward.

In addition to Hinkley, one of the most significant large nuclear projects going forward in the UK is Sizewell C. Through the 3.2GW power station planned for Suffolk, EDF promises to deliver enough low-carbon electricity to power six million homes from its two EPRs (European Pressurised Reactors). The station will be located next to Sizewell B and is expected to be generating power for at least 60 years.

The project has been met with both praise and criticism. Those behind the Stop Sizewell C campaign believe that the project will be too slow and expensive to have a profound impact on our climate targets, and are pushing for prioritisation of alternative low-carbon technologies.

After four rounds of public consultation involving 10,000 East Suffolk residents, Sizewell C was given the green light on 20th July when its Development Consent Order application was approved.

“In the local community, according to the last ICM poll, twice as many people are in favour of the power station as are opposed to the power station,” Julia Pyke, Sizewell C’s director of financing told The Engineer. “We fully respect people who are opposed to the power station, but they don’t represent the majority of the population.”

Discussion is now progressing on funding, with a Financial Investment Decision expected in 2023. The Office for Nuclear Regulation will also need to grant Sizewell C a Nuclear Site Licence before construction begins.

Alison Downes, director of Stop Sizewell C, described the decision as an instance of government being ‘forced to ram through a damaging project to shore up its energy strategy’.

Commenting on reports that the Planning Inspectorate had recommended the project be refused consent, she said: “Not only will we be looking closely at appealing this decision, we’ll continue to challenge every aspect of Sizewell C, because — whether it is the impact on consumers, the massive costs and delays, the outstanding technical questions or the environmental impacts — it remains a very bad risk.”

Among the technical questions lies the issue of how the site will receive an adequate water supply. Pyke said that whilst this was cited as a concern from the planning inspectorate, the situation is more nuanced than some are suggesting by arguing that the Secretary of State overruled the planning decision.

“The planning inspectorate’s conclusion was that the benefits strongly outweigh the disadvantages, but it did conclude that at the end of its examination period, we had not provided sufficient information in relation to our water strategy,” Pyke said, adding that the Secretary of State then asked for further information on water which was provided, deemed ‘satisfactory’ and approved.

“We’re doing two things, both of which should actually bring long-term benefit to Suffolk. We’re installing a temporary desalination for the first few years of construction … Suffolk is an arid county, it’s short of water completely regardless of building Sizewell C.

“So in the long run, the water companies are looking at desalination and it’s possible that our starting off desalination on that coast will actually turn out to be quite helpful.” She added that secondly, Sizewell C will pay for a pipeline to bring more water into East Suffolk from an area where water is more plentiful, aiming to bring a ‘lasting legacy benefit’ to the area.

Sizewell C has been awarded £3m in government funding for a direct air capture (DAC) project alongside consortium partners Nottingham University, Strata Technology, Atkins and Babcock. DAC is a method of absorbing CO2 from the atmosphere and storing it for industrial use.

“The really interesting synergy that we think Sizewell C can bring to the table and that nuclear can bring to the table is heat,” said Shekhar Sumit, head of energy transition at Sizewell C.

“There was a recent paper by Columbia University which recognised nuclear as being the lowest-cost producer of low-carbon heat … What we are exploring is the ability to extract this low-carbon heat from Sizewell C and use it for this DAC process, which will actually make the process much more efficient and help to drive it forward.”

The funding is part of the government’s Greenhouse Gas Removal (GGR) competition and will allow the consortium to build a prototype DAC unit away from the Sizewell C site.

Sizewell C is also exploring future hydrogen production, as well as use of hydrogen during construction of the plant itself, Sumit told The Engineer. This includes hydrogen-powered vehicles for transportation of components and low-carbon hydrogen to power construction equipment on the site.

“That of course will be helpful on one hand to reduce our emissions, but at the same time we think that can help drive forward a hydrogen ecosystem itself in the east of England,” he said. “All of the infrastructure and facilities that will be created … will be potentially helpful for other hydrogen users in the area.

“For example, Sizewell C have been in touch with Freeport East, they are very similarly interested in using hydrogen-derived fuels to decarbonise their port processes. We recently participated along with them on this government funded Maritime Decarbonisation Competition, so there’s this really interesting synergy of approach coming together.”

Responding to cost concerns, Pyke pointed out that the Hinkley £92.50 MwH strike price was much criticised at the time, but consumers would be saving ‘well over £2bn a year if Hinkley was on now’.

“What looks expensive one year might look like something that will save consumers £2bn per year the next year — what is cost, what’s the value of energy security and of reducing reliance on the gas market?” she said. “The second thing is that of the £92.50, only £11 represents the cost of construction.

“The absolute key with Sizewell C is of course to control the construction costs to the maximum extent we can, but massively, it’s to use an income model — which the government has now developed — to bring down the cost of money alongside the construction costs.

“Not only are we confident that we have a much more mature and better-developed cost estimate than Hinkley did when it started, but even if there are cost overruns, which we will do everything we can to avoid, the impact on consumers won’t be great. In this parliament, consumers won’t pay more than about £2 per household per year.”

She added that household electricity bills will be reduced with nuclear, compared to being wholly reliant on renewables and storage.

“We’re very in favour of renewables and all low-carbon technologies, we’re not looking for a wholly nuclear energy system, we’re looking for the right amount of nuclear in the mix,” she concluded.

Another significant player in the UK’s new nuclear scene is Rolls-Royce SMR, which has been backed by £210m UKRI funding to deploy a fleet of the ‘compact’ power stations.

The company formed as a separate entity from majority shareholder Rolls-Royce, its other shareholders being Qatar Investment Authority (QIA), BNF Resources UK Ltd and Exelon Generation Ltd.

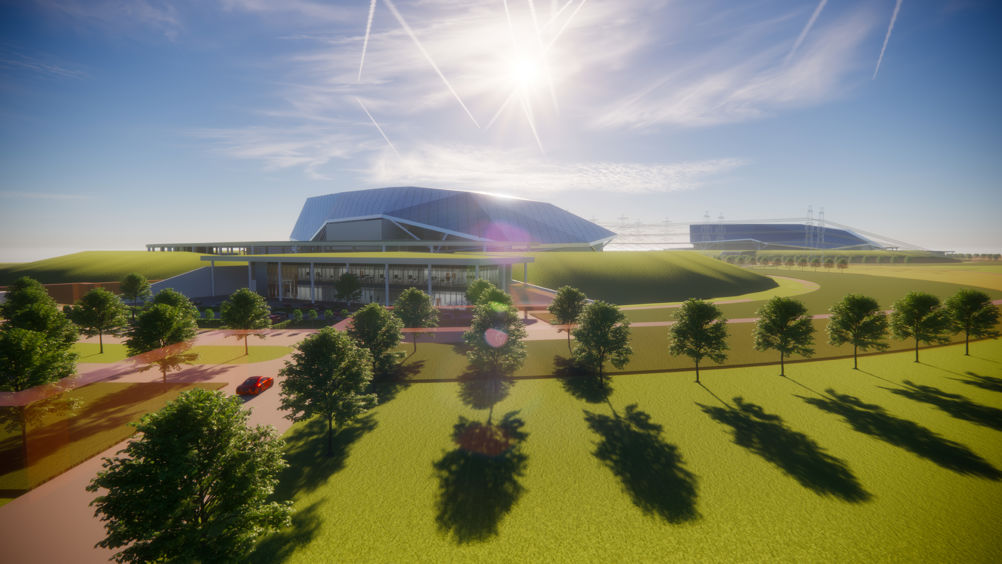

The 470MWe power station design is planned to occupy around a tenth of the size of a traditional plant and utilises familiar PWR technology — but is described as ‘radically different’ in its off-site modular construction approach.

During the Westminster Energy, Environment & Transport Forum’s 2022 ‘Next steps for the nuclear sector’ conference, Rolls-Royce SMR’s director of strategy and business development Alan Woods explained why the project is being categorised as a small modular reactor despite being significantly larger than a typical SMR design (usually 300MWe or less).

“The S for small — for us, that’s not about picking an arbitrary power output, it’s about maximising the power within the physical constraints we put on the design. And for us, the physical restraint we put on the design … is a requirement for each module to be transportable.

“It’s about commoditisation, it’s about repeatability, it’s about designing the power plant in a manner where we can get a production line approach to the fabrication of those modules.”

The modules for the first Rolls-Royce SMR will be manufactured in UK factories before being transported for rapid assembly on-site. In July, a shortlist of locations was revealed for the first factory which will manufacture the power station’s heavy vessels. These include Wales, Sunderland and Carlisle.

Two more factories will then manufacture the SMR’s civil modules and the mechanical electrical and plumbing (MEP) modules.

Considering locations for its first station, Rolls-Royce SMR has revealed that it is targeting North Wales and West Cumbria due to benefits including the existing grid connection, infrastructure and skilled workforce.

The company has spoken of ‘strong possibilities’ for opportunities in West Cumbria, with director of corporate and government affairs Alastair Evans commenting on the potential for a Rolls-Royce SMR to feed energy-intensive industrial processes in Britain’s ‘nuclear heartland’ including at the Sellafield site.

With intentions to create a global and scalable solution, Rolls-Royce SMR is targeting £250bn of exports and has Memorandums of Understanding in place with Estonia, Turkey and the Czech Republic.

“What we’re now seeing is real interest in moving at pace with the deployment of SMRs, as opposed to what I’d categorise historically as people getting interested, doing a lot of assessment of what SMRs might mean for them,” Woods said during the event. “There is a real shift of rapid deployment focus from many countries, not just across Europe but around the world.”

Where innovation is concerned, Woods stressed that while the company is ‘challenging the boundaries of innovation’, it has to be for benefit - introducing ‘technology for technology’s sake’ could just introduce more challenges with the regulator, he explained.

“We have some innovations associated with the power plant that we’ve parked, whether they are system design innovations or manufacturing innovations — we’ve parked them because we know they could cause challenges through that early regulatory cycle and we don’t want to do that.

“This is a power station, not just a reactor. And there is a huge amount of innovation in terms of how we go about removing that risk to make this buildable, deliverable, investable.”

Whilst there is hope in new nuclear, many have expressed concern around the so-far unsolved conundrum of how to safely store and dispose of our waste. The government is aiming for the development of a Geological Disposal Facility (GDF), but a suitable location is yet to be confirmed. Many believe that until a solution is found, the UK should put the brakes on the new nuclear rollout.

During the WEET 2022 conference, the Nuclear Institute’s Jasbir Sidhu argued that we need to begin by addressing the way we speak about nuclear waste: to stop calling it ‘waste’, and instead view it as a resource that future generations could tap into.

“Let’s change the language that we’re using. If we change it, the taxonomy should start falling in place,” he commented. “There’s no market for its potential reuse today, but that doesn’t mean that future generations can’t make use of it.”

Candida Whitmill, managing director of SMR developer Penultimate Power UK added: “Having it as an actual asset, and not as a concern, is something that we really need to work on and the fact that we are now developing reactors that can use spent fuel is something which really needs to come into the narrative.”

Next-generation nuclear reactors could be game-changing for the sector in addressing this issue, such as Moltex Energy’s novel Stable Salt Reactor Wasteburner (SSR-W), which can recycle and utilise waste from existing nuclear power plants. The first reactor of this kind is planned for New Brunswick in Canada, to be built by NB Power and estimated to be operational by the early 2030s.

Plenty of challenges will arise on the UK’s road to decarbonisation and energy security, and there is no winning technology that will provide a single solution to such a complex issue. But whatever your stance on nuclear, it’s set to play an increasingly big role in the energy transition — and those making it happen are determined to prove its value.

Hard hat mounted air curtain adds layer of protection

Something similar was used by miners decades ago!