It is estimated there are 50 million people on the planet living with dementia today, a number the World Health Organisation predicts will treble over the next 30 years as average life spans increase. The issue has been described as a time bomb – the biggest healthcare challenge of the 21st century. Although there is no known cure for the disease, technology is playing an increasingly important role in helping people live with dementia, particularly in their own homes.

“Dementia is now the biggest killer in the UK,” said Prof David Sharp, a neurologist at Imperial College London and head of a new £20m dementia research centre. Located at Imperial’s West London campus near White City, the facility will apply AI, robotics, sensors and software to create dementia-friendly homes when it opens in June this year.

“We’ve got 850,000 people living with dementia today,” Sharp told media at a recent event to launch the centre. “We’ve got an ageing population. By 2050, we’re going to have about two million people living with dementia.

“From my perspective, I think the system for caring for patients with dementia is broken. I think most patients and carers come into contact very infrequently with healthcare professionals. What that means is that preventable problems develop. One of the facets of that is around hospital admissions. So around 25 per cent of all the NHS beds are occupied by people living with dementia, and we estimate that about 20 per cent of those admissions are potentially preventable.”

Preventable admissions can be the result of anything from dehydration and falls to things like urinary tract infections (UTIs), which are particularly common in dementia patients and often result in lengthy hospital stays. Cutting the number of these admissions would reduce the strain on both the NHS and dementia patients themselves, for whom hospital visits can be distressing. According to Sharp, technology in the home could have a major impact on how dementia’s effects are detected and how the disease is treated.

“We have treatments for UTIs, we’re just not implementing them quick enough,” he said. “We think that technology and new engineering advances are going to help us to do that. What we propose is that the centre will develop an intelligent environment, so really a cost-effective home that uses advanced engineering solutions and artificial intelligence to support and protect patients living in their own home, which is where people want to stay for as long as possible.”

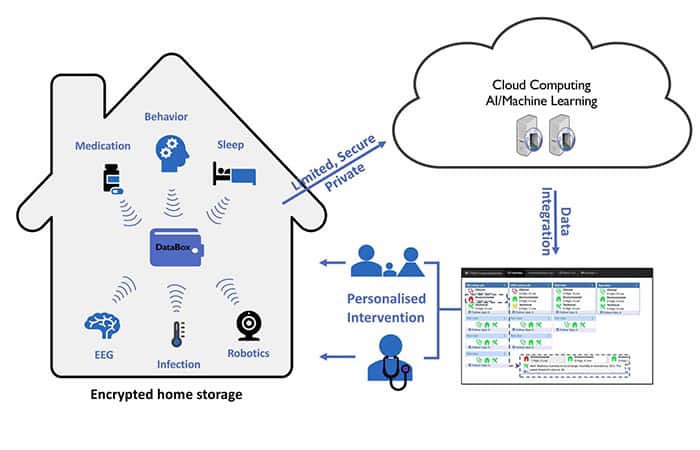

At the heart of the system will be a suite of advanced sensors deployed throughout the home, recording the most relevant information for patients who are living with dementia. This includes things like sleep assessment, detailed behaviour assessment, medication effects, brain activity changes and infection monitoring. The information from these systems will feed into a system called Databox, which will essentially be a small home-server that will give patients control over their own data, while also providing access to approved healthcare professionals.

As well as evaluating technology that is already available, the centre will test completely new hardware designed specifically for the project. An earpiece sensor developed in-house at Imperial will provide information on gait and sleep, as well as acting as a mobile EEG, recording brain activity over extended periods of time. Elsewhere, low-cost miniaturised radar technology will generate detailed data on patient movement and behaviour.

“We have a prototype of an ear EEG system that can be used to track brain activity over long periods of time, so we’ll be evaluating that,” Sharp explained. “We’re also going to be developing new biosensors to measure infection state as well as the earliest signs of the development of dementia from the blood.”

AI and machine learning will help identify patterns in the data and guide decision making. Crucially, the system should provide a more rounded view of the disease and its impacts, in comparison to the brief patient snapshots garnered from medical appointments. This will help healthcare professionals to evaluate the effectiveness of treatments in real time as well as enhance patient safety.

“We want to use robotic devices and other ways of changing the environment to try and improve safety and to try and support people to live for as long as possible in the home,” said Sharp. “We think the system overall will have a number of benefits. We think it will personalise care, it will improve health autonomy, it will improve communication across healthcare teams and it will improve safety by allowing us to identify problems that might be developing in the home environment.”

In a bid to ensure that the research is practical and relevant, the centre will work with Imperial’s design centre, Helix, to get early feedback on prototypes from patients and carers. The most promising technology will then be trialled in the homes of around 50 people affected by dementia, with a new group of 50 rotated in every six months. This model will enable the team to assess different combinations of technology to find out what blends well for the best overall benefit. While certain devices are already commercially available, Sharp expects some of the newer developments to reach the market within the next five years, with the aim of keeping the tech small, low-cost and scalable.

“I think we’re close to having something that’s really usable in a wide context,” he said. “I think the wins will be across a wide range of things. I think we’ll be targeting reducing that 20 per cent figure of unnecessary hospital admissions.

“We’re very interested in the use of smartphone apps, for example, for monitoring certain aspects of disease progression. We’ve already funded that and we have a system for monitoring memory and attention and how people are affected. And that will be free to download.

“So there’ll be an element that anyone will be able to access, from anywhere in the world.

“Of course some of the more complicated technology will come at a cost.”

The vision is that someone diagnosed with dementia in the near future could be prescribed a package of hardware and software, perhaps via the NHS. GPs might have a dashboard of different apps suited to individual needs, while specialists might kit out homes in the same way internet and TV providers do today. Ultimately, the system should enable healthcare professionals to engage with dementia patients more effectively, but also much more meaningfully.

“We think the technology will transform the efficiency, the use of the resources available, improve the way GPs are operating, reduce hospital admissions, keep people out of care homes and out of hospital for as long as possible,” said Sharp.

“That has major economic wins, and people also want to stay in their homes with their loved ones as long as possible. They don’t want to be in a nursing home or sitting for three months in a hospital bed because they had a UTI but we couldn’t treat it. That’s the target. That’s a win all round.”

MORE ON MEDICAL & HEALTHCARE AND ELECTRONICS AND COMMUNICATIONS

Comment: The UK is closer to deindustrialisation than reindustrialisation

"..have been years in the making" and are embedded in the actors - thus making it difficult for UK industry to move on and develop and apply...