The past 20 years or so has seen a transition regarding the value of heritage among the car manufacturing grandees, moving from being viewed with a vague indifference to becoming a core element for promoting brand awareness. The lustre that a successful past can bring to a marque is now mined through everything from lapel badges to company run museums and active support for historic events like the Goodwood Festival of Speed.

The latest evolution of the promotional product drawn from an automotive hinterland is the “continuation series car”, where a manufacturer will create a limited run of new examples of an old, iconic model. The original cars will always be ahead in cachet and value but through being built by the factory these are more desirable than any third party replica, no matter how accurate that replica may be.

Despite the eye watering price tag that inevitably comes with a high quality limited edition product from a mass manufacturer, the progress of legislation and regulation mean they are invariably not road legal and therefore destined to be either altered to conform with the current laws, trailered to a show, locked away accumulating value or driven on track. Despite these major drawbacks there has never been a problem selling them and so far we have seen Jaguar revive the iconic lightweight E Type racer while Aston Martin took a different route in appealing to the inner 12 year old of your average multi-millionaire with the “Goldfinger” DB5.

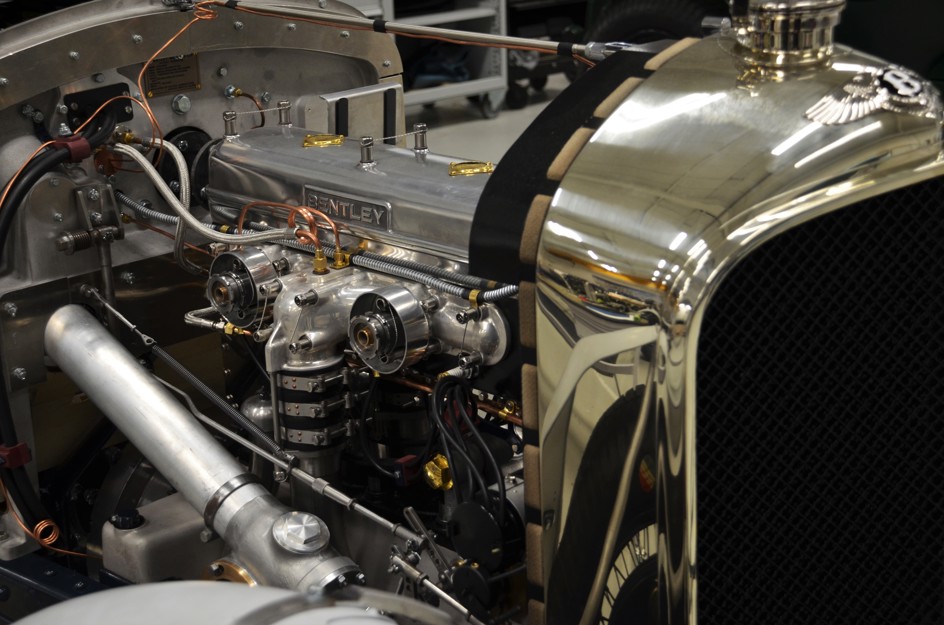

Bentley have now joined the fray but uniquely have decided to re-manufacture a pre-war design, the supercharged 4 ½ “Blower” from 1929. The choice of car caused huge excitement but if historical context is considered alone then it may be seen as a curious one. The 3 litre was the first production Bentley, the Speed 6 arguably the most successful in competition and the 8 litre the acknowledged embodiment of company founder, W.O. Bentley’s, overarching vision. The Blower didn’t win any major races and its defining feature, the supercharger, was described by W.O. himself as “a corruption.” However, consider instead that it was conceived by the dashing “Bentley Boy” Tim Birkin (its iconic moment of glory was when he used it to break the Mercedes of Caracciola at Le Mans in 1930 to the benefit of the works team) the exotic allure bestowed by that same supercharger and it makes perfect sense.

Delving 90 years into the past for your halo product does bring particular problems but, perhaps surprisingly, these weren’t related to the design element of the project. Bentley still holds the vast majority of production drawings and as Birkin’s Le Mans car, the actual one he used to such great effect in 1930, is now a part of their heritage collection this could also be reverse engineered in the rare instances where drawings were missing. When it came to actually building the cars though, it was a different story.

The continuations from Jaguar and Aston Martin use manufacturing techniques still in currency, if not exactly the norm (pressed panels and fabricated tubes welded together for the chassis, sealed beam headlights, etc) whereas Bentley were faced with sourcing skills that have more in common with the age of steam. Mike Sayer, Bentley’s head of Product Communications and guide for our visit, explained how in some cases it made more sense to look outside of the company for the relevant expertise. A healthy “heritage” engineering industry in Britain means that complex chassis rails can be formed and riveted by boiler makers while a father and son team are able to supply headlights of a quality demanded by such a high prestige project.

As with the original cars, the Blower Bentley remains hand built and all major components are assembled, checked, modified and refined before disassembly and final painting. Its only after this that the build proper begins with the kit of pre-matched parts. Starting as the bare chassis at one end of the build hall, each example works its way along to completion at the opposite end. Remarkably, only four concessions have been made for use in the modern world: the hand charged fuel pressurisation has been exchanged for an electric pump, the fuel tank has a foam baffle, an electric fan helps with today’s traffic and a modern alternator is discretely housed within an ersatz dynamo casing.

The responsibility for building the cars lies with Bentley’s in-house limited run specialist, Mulliner. Rather than the usual mass or even batch production processes, each team member will attend to some particular task on one of the six or seven examples in build at any given time on a daily assigned basis. No wonder then that, with a run of only a dozen cars, while the first are already delivered the last won’t be completed until the end of this year. However, this does allow for ultimate customisation and the ability to achieve a phenomenal level of finish. The chance to develop existing expertise within the workforce has also been exploited. “While many expert suppliers were involved in the project, the build of each of the cars has taken place entirely in Crewe and so the development of new skills amongst Mulliner’s technicians has been a significant bonus of the project,” claimed Sayer.

“Every day we learn something new about these beautiful designs, and how they were originally put together in the 1920s.” This along with recent commitments to develop the “future of coach-building”, and the taking on of record numbers of trainees illustrate that designs in need of high levels of craftsmanship are central to Bentley’s future portfolio.

Despite the Blower being essentially an established product there has still been an extensive development programme, predominantly using “Car 0” - the prototype which will be retained by the company. During our visit, this was in being serviced following a recent test. It would appear that one of the reasons for this is the large variation in both the owner and their intent, creating a number of customer unique specific validation requirements. Ferrari follow the strategy of only selling their limited high profile cars to vetted and trusted long term owners, sometimes with stringent limitations. Blowers by contrast have been bought by customers who have never owned a Bentley before (or even a vintage car) and some have already been confirmed as destined for the race track, a highly demanding environment.

Our visit was concluded with a ride in the Birkin Blower around the local back roads to experience what it is that makes these cars so special. Apparently the new cars are “tighter”, having no requirement to preserve worn components on a car thought to be 90 per cent original from its glory days of 90 years ago. Even so, the ride was surprisingly smooth, no doubt helped by the inherent inertia that comes with an all up weight of 1.7 tons. The engine delivers its power in an almost lazy way, limited as much as anything by the long inlet tract coupling supercharger to engine which invariably induces a backfire in response to too enthusiastic an application of the accelerator.

Even in the blustery showers that accompanied us though, the charm and romance of such a car shines through. All 12 continuation Blowers sold immediately and despite the price tag of £1.8 million the quality of the engineering coupled to the car’s truly iconic status and the factory support in development gives a feeling that it is money well spent.

Stephen Mosley also writes under the name of Actuarius and was shortlisted for the Guild of Motoring Writers ‘Feature Writer of the Year Award’ in 2021”

Comment: Brute force can not solve autonomy challenge

My brother has lost his licence in his forties due to an eye problem and he'd quite like a self driving car.