Imaging technique helps predict breast cancer response to chemo

A new imaging system developed at New York’s Columbia University could provide insight on breast cancer patients’ response to chemotherapy within just two weeks.

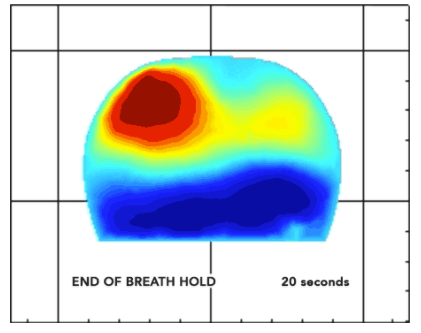

The method, which uses red and near-infrared light, measures the blood flow dynamics in the breasts of women undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy. This type of treatment is generally given to women newly diagnosed with invasive, but operable, breast cancer for five or six months before they undergo surgery. Women who have a complete response – where the chemo eliminates all active cancer cells – have a lower chance of cancer recurrence.

“Patients who respond to neoadjuvant chemotherapy have better outcomes than those who do not, so determining early in treatment who is going to be more likely to have a complete response is important,” said study co-leader Dawn Hershman, MD, head of the Breast Cancer Programme at the Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer Centre.

“If we know early that a patient is not going to respond to the treatment they are getting, it may be possible to change treatment and avoid side effects.”

Register now to continue reading

Thanks for visiting The Engineer. You’ve now reached your monthly limit of news stories. Register for free to unlock unlimited access to all of our news coverage, as well as premium content including opinion, in-depth features and special reports.

Benefits of registering

-

In-depth insights and coverage of key emerging trends

-

Unrestricted access to special reports throughout the year

-

Daily technology news delivered straight to your inbox

Water Sector Talent Exodus Could Cripple The Sector

Maybe if things are essential for the running of a country and we want to pay a fair price we should be running these utilities on a not for profit...